Ptolemy I

Ptolemy I Soter1, king of Egypt, son of Arsinoe2 by an unknown father, possibly Lagus3, born in Eordaea, Macedon, c369/8 or c360/3564, member of the Royal Bodyguards of Alexander III, king of Macedon and Great King, 3305, Satrap of Egypt within 7 days of the death of Alexander on 28 Daisios (Mac.) = 29 Ayyaru (Bab.) = 11 June 3236, which probably became the basis of his regnal year6.1; took up the post a few months later 6.2; King of Egypt between 1 Thoth year 1 (Eg.) = 7 November 305 and 30 Skirophorion archonship of Euxenippus (Ath.) = c. 10 July 304, most probably in spring 304, possibly 29 Daisios year 19 (Mac.) = c. 4 June 3047; victor in the pair for foals in the 69th Pythian Games of 3147.1 and in the chariot races in the Olympic Games of an unknown Olympiad7.2; made Ptolemy II coregent c. 25 Dystros year 39 (Mac.) = c. 28 March 2848, died probably Artemisios / Daisios year 41 (Mac.) = c. April-June 2829, probably of illness in old age10, incorporated in the dynastic cult with Berenice I by Ptolemy IV in 215/14 as the Saviour Gods, Qeoi SwthreV11.

Ptolemy I's titles as king of Egypt were:12

Horus wr-pHt j nsw on j13

Two Ladies jT j-m-sxm HoA Tl14

Golden Horus <unknown>

Throne Name (1) stp-n-Ra mrj-Jmn15

(2) xpr-kA-Ra stp-n-Jmn16

Son of Re ptlmjsPtolemy I had four, possibly five, known marriages or liaisons:17

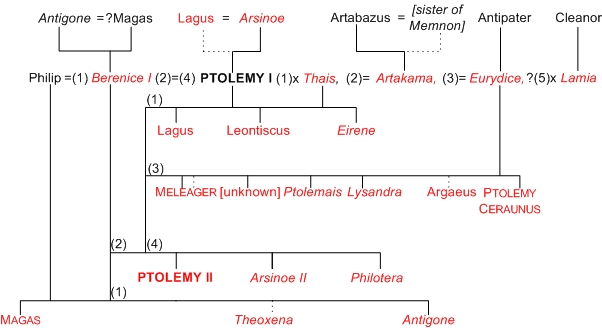

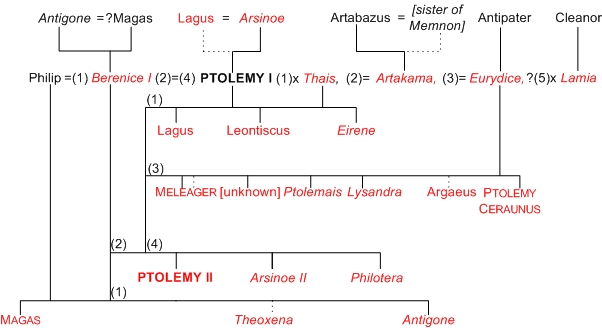

Ptolemy I first conducted a liaison, then marriage, with Thais, an Athenian hetera of unknown parentage, by whom he had Lagus, Leontiscus and Eirene18;

Ptolemy I second married Artakama, daughter of Artabazus, by whom he had no known children19;

Ptolemy I third married Eurydice, daughter of Antipater, regent of Macedon20, by whom he had Ptolemy Ceraunus21, an unknown son22, Ptolemais23 and Lysandra24, probably Meleager25 and possibly Argaeus26;

Ptolemy I fourth married as her second husband Berenice I, daughter of Antigone, a cousin of Eurydice, probably by Magas27, by whom he had Ptolemy II28, Arsinoe II29 and Philotera30.

In addition the children of Berenice I by her first marriage to Philip, Magas31, Antigone32 and probably Theoxena33, became members of the royal family; and

Ptolemy I fifth probably conducted a liaison with Lamia, an Athenian hetera34, daughter of Cleanor35, by whom he had no known children.

Ptolemy I was probably not the father of Ptolemy son of Ptolemy, bodyguard to Philip III.36

In addition, it was agreed in 308 that he would marry Cleopatra, daughter of Philip II of Macedon and Olympias and full sister of Alexander III, but she was murdered before the marriage could take place by agents of Antigonus Monophthalmos.37

[1] PP VI 14538. Gr: PtolemaioV Swthr. The epithet Soter ("Saviour") was explained in two ways in the ancient literature. According to Pausanias 1.8.6, it was awarded to Ptolemy by Rhodes after he lifted the siege of Demetrius Poliorcetes in 305/4. While this explanation is widely accepted by modern scholars, R. A. Hazzard (ZPE 93 (1992) 52) points out that (a) Pausanias is provably inaccurate on other points related to the Ptolemies (b) the title is not mentioned by Diodorus in connection with Rhodian events, even though he describes them in detail and is drawing on lost Rhodian sources favourable to the Ptolemies, and (c) contemporary Rhodian inscriptions related to the cult of king Ptolemy do not use the title. The second ancient explanation was that it was given to Ptolemy after he saved the life of Alexander from the Oxydrakai. This explanation was mentioned by both Arrian (Anabasis 6.11.3) and Curtius (9.5.21) to be dismissed by both since Ptolemy's own memoirs placed him elsewhere at the time.

R. A. Hazzard, ZPE 93 (1992) 52 at 56 n. 35, claims that the first dated use of the title for Ptolemy I occurs on silver tetradrachms tetradrachms from Gaza dated to year 23, which J. N. Svoronos, Die Münzen der Ptolemäer No. 821 (pl. 24.2) assigned to Ptolemy II (263/2). He further notes that Ptolemy II first describes himself as a son of Ptolemy Soter in 259, after the rupture with Ptolemy "the Son", in pRev I.1; before this he is invariably king Ptolemy son of Ptolemy. Hazzard explains all this, including the Oxydrakai story (R. A. Hazzard, Imagination of a Monarchy: Studies in Ptolemaic Propaganda 3ff.), as part of a propaganda effort by Ptolemy II to relaunch the prestige of the monarchy after defeats in the second Syrian war and the Chremonidean war. He supposes that the title was officially assigned to Ptolemy I at this time.

This is not quite correct. The coin in question was reassigned to Ptolemy III (year 23=225/4) by O. Mørkholm, INJ 4 (1980) 4 on solid stylistic grounds. This leaves the earliest dated coins with the Soter legend as year 25 of Ptolemy II = 261/0, e.g. Svoronos No. 650 (pl. 19.20) from Tyre. Since Svoronos published Tyrian coins from the previous 5 years which did not use the title, it is clear that it was not introduced into Phoenician coinage before 261/0. Table 1 in R. A. Hazzard, Imagination of a Monarchy 18f. accepts Mørkholm's redating.

Against this analysis, and in favour of the traditional one, C. Johnson (AHB 14.3 (2000) 102) argues that (a), (b) and (c) prove nothing, and that there are two inscriptions contemporary with Ptolemy I using the title: OGIS 19, a statue dedicated to king Ptolemy Soter, and O. Rubensohn, AfP 5 (1905) 156 no 1, a dedication to king Ptolemy and queen Berenice, Qeoi SwthreV. But Johnson agrees that the first could be a reference to Ptolemy IX Soter II, and the last is problematic since the title is assigned jointly to Ptolemy I and to Berenice I, not to Ptolemy I alone.

The deification is also a difficulty. P. M. Fraser (Ptolemaic Alexandria II 367 n. 229), who discusses the same inscription, notes that there are no references to Qeoi SwthreV in the reign of Ptolemy II, and the title is otherwise unknown in the dynastic cult until Ptolemy IV; he explains its presence here as due to special circumstances related to the content of the inscription.

In light of Fraser's note, which Hazzard cites (Imagination of a Monarchy 6 n. 15), it is especially curious that he repeatedly states that a cult of the Qeoi SwthreV was established by Ptolemy II on his accession (e.g. Phoenix 41 (1987) 140 at 150; Imagination of a Monarchy 3, 15, 31, 43 etc.). He nowhere adduces any proof of this that I can find. His assertion that the title appears in SEG 27.1114 is simply wrong. He amends the text of Callimachus (Imagination of a Monarchy 43) to insert the divinity. The only possible occurrence I know is the purported dedication inscription of the Pharos lighthouse to the Qeoi SwthreV by the architect and courtier Sostratus (Lucian, Hist. Conscr. 62) -- but, as noted in P. M. Fraser, Ptolemaic Alexandria I 18, these gods could equally well (and, in the circumstances of the story, more likely in my opinion) be the Dioscouroi, Castor and Pollux.

I think Hazzard has demonstrated that the epithet did not become part of the official dynastic formulary until 261. However, this is insufficient to prove that the title was first applied to Ptolemy I at that time. There is abundant evidence that Ptolemy I and Berenice I were jointly referred to as SwthreV well before 261, as Hazzard himself notes (see above). P. M. Fraser, BSAA 41 (1956) 49 at 50 n. 2 and P. M. Fraser, Ptolemaic Alexandria II 367 n. 229, noted undated examples of the SwthreV which were certainly well before 261: OGIS 22 from Cyrene, before the revolt of Magas; SEG 18.636, the dedication of Archagathus; and OGIS 724, under Ptolemy II and Arsinoe II. To these, Hazzard added SEG 27.1114, dated 12 Dystros year 18 = c. 9 March 267. Fraser cites other examples under Ptolemy II but these are less clearly datable before 261.

While O. Rubensohn, AfP 5 (1905) 156 no 1, does not show Ptolemy I using the epithet in his lifetime, it does show the royal couple using it jointly in his lifetime. Since Berenice I certainly had no claim to it in her own right, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that it was actually used to identify Ptolemy I in his lifetime.

Chronologically, the issue is important for establishing the date of SIG3 1.390 = IG XII 7.506, the decree of the League of Islanders recognising the Ptolemaieia, which plays a role in setting limits to the date of death of Berenice I. Ý

[2] Porphyry FGrH 260 F 2 2, in Eusebius, Chronicorum (ed. Schoene) 161; Satyrus FGrH 631 F 2; Aelian fr 285.17 in Suda, LagoV. Ý

[3] Arrian, who drew on Ptolemy's memoirs, and most other ancient sources, simply call Ptolemy "son of Lagus". However, Pausanias 1.6.2 and Curtius (9.8.22) both record a story that his father was Philip II of Macedon. N. L. Collins (Mnemosyne 50 (1997) 436) notes that this claim is not consistent with Curtius' description of Philip III Arrhidaeus as the closest in blood to Alexander, nor does Diodorus refer to this relationship even when discussing Ptolemy's engagement to Cleopatra, who would be his half-sister if it were true; nor do the names of Ptolemy's children by Thais hint at any connection to the Argaead line.

One might also note that Pausanias 8.7.6 tells us that Philip II was assassinated at the age of 46. Since the date of this event is well-established as 336, he was born in 383 or 382. If Ptolemy was born in 369/8 as Lucian claims, then Philip II was 13 or 14 at the time of his conception -- possible but rather unlikely. Moreover, Pausanias 1.6.2 claims that Philip married Ptolemy's mother Arsinoe off to Lagus while she was pregnant. As a 14-year old prince, during the reign or regency of his brother's murderer Ptolemy of Alorus, and who was sent as a hostage to Thebes very shortly after (Plutarch, Pelopidas 26.4), it also seems unlikely that he was in a position to do so.

Concerning his relationship to Lagus, Collins notes that Ptolemy is never referred to as the son of Lagus in contemporary records, but only as "king Ptolemy" or "Ptolemy of Macedon", and further notes that the Talmudic commentary on the translation of the Septuagint, which most likely occurred late in Ptolemy's reign, replaced the Greek term for 'hare' (lagoV) by a euphemism, since it was derogatory to Ptolemy's wife, or rather, in Collins' view, his mother (Talmud Babli, Megilla 9A).

Now, Curtius (loc. cit.) does not endorse the claim of Philip II, merely noting that Ptolemy's mother Arsinoe was one of his concubines, and Aelian (fr 285.17-20 in Suda, LagoV) is explicit that Ptolemy was not the son of Lagus, while Plutarch (Moralia 458A-B) refers to the "dubious" birth of the king. Further, Pausanias (1.6.2) describes the claim of Philip II only as a Macedonian belief. Collins also cites a statement by Porphyry (as quoted in Eusebius, Chronicorum I (ed. Schoene) 235) noting that the successor of Ptolemy Ceraunus and his brother Meleager, Antipater Etesias, was chosen as king of Macedon because of his lack of royal (Macedonian) descent, implying that Ceraunus and his brother, by contrast, were of royal descent. Since Antipater was Cassander's nephew, the alleged royal descent of Ptolemy Ceraunus and Meleager must come from the Argead line. On these grounds Collins proposes that the story that Philip II was Ptolemy's father was propaganda of Ptolemy Ceraunus, designed to justify his claim to the Macedonian throne by showing that he was a male-line if distaff member of the Argaead dynasty.

Collins concludes, I think correctly, that Arsinoe was married off to Lagus while pregnant with Ptolemy, as stated by Pausanias, but that his true father was unknown. The description of Ptolemy as "son of Lagus" therefore refers to Lagus as his official or adoptive father, the husband of his mother, rather than to his biological father.

There is one possible piece of evidence against this analysis. W. W. Tarn, JHS 53 (1933) 57 cited a story told by a certain Euphantus, that a certain Callicrates was a flatterer of Ptolemy III who "was so clever that he not only wore a ring with the figure of Odysseus engraved on it, but also named his children Telegonus and Anticleia." He argues that the point of the story is that Anticleia, mother of Odysseus, is said to have given herself to Sisyphus, the cleverest man known, before her marriage to Laertes, so that her son might be the son of the cleverest man alive. [He was unable to explain the significance of Telegonus, son of Odysseus by Circe.] He concludes that this is a reference to the story that Ptolemy I was really a son of Philip II, and therefore that the story should really be attributed to Ptolemy I, not Ptolemy III, showing that it was in fact current in Ptolemy I's lifetime.

N. L. Collins, Mnemosyne 50 (1997) 436 at 436 n. 1 says that her analysis, showing that the story originated in Macedonia after Ptolemy I's death, disproves Tarn's argument. However, she then leaves Euphantus' story hanging. Tarn's explanation of the significance of Odysseus and Anticleia, it seems to me, is perfectly reasonable. However, his conclusion that the story should therefore be assigned to Ptolemy I does not follow, because it assumes that Ptolemy III would not be flattered by the implication that he was descended from Philip II. By his time, the political significance of the story was as dead as Ceraunus, but the story itself would certainly be circulating. So there seems no reason to reattribute the king based on Tarn's analysis. Ý

[4] Birthplace: Arrian, Anabasis 6.28. Stephanus of Byzantium names his birth town as Orestia, the exact location of which is uncertain. Age: Lucian, Makrobioi 12, states that Ptolemy abdicated at age 84, two years before his death. However, Plutarch, Alexander 10.5, shows Ptolemy as a close contemporary of Alexander, who was born 356, which would have Ptolemy born perhaps a couple of years earlier. If Lucian is correct, he may have been named after the ruling Macedonian king at the time of his birth Ptolemy Alorus (368-365). Ý

[6] Arrian, Successors 1.5.; 7 days: Curtius 10.10.9

The problem of the exact Julian date of Alexander's death has most recently been examined in L. Depuydt, WO 27 (1997) 117. The primary source is now BM 45962, a fragment of a Babylonian astronomical diary for 323/2. It includes a note for 29 Ayyaru that "the king died". The dating of the tablet to 323 is a result of retrocalculating the various surviving observations. The Babylonian day started at sunset, and we know from BM 34075 that Ayyaru had 29 days that year, so 29 Ayyaru covers the evening of 10 June and the daylight of 11 June 323, and the king must be Alexander. Because daily observations were structured into two parts, with night observations first, indicated by "night of <date>", and this phrase is missing from the date associated with Alexander's death, he must have died in the daylight half of 29 Ayyaru, i.e. on 11 June 323.

The royal Diaries (Plutarch, Alexander 76.9) give the time of day he died as deikh. This term was commonly translated as "evening", which initially led to the assumption that Alexander actually died on 10 June 323. This would be the nighttime part of 29 Ayyaru, which contradicts BM 45962. However, Depuydt quoted clear examples, first assembled by Bilfinger in 1888, that place deikh before sunset, i.e. it should actually be understood to mean "late afternoon", specifically (at least in Attica) between the 9th and 10th hour of the day. Given that the actual duration of the daylight hours was about 14 hours by modern reckoning, Depuydt estimates the time of Alexander's death as 4-5 PM.

A variety of dates are given in the literary sources. These may be explained as follows:

30 Daisios (Plutarch, Alexander 75.6, quoting the memoirs of Aristoboulos, a close companion of Alexander, who was present). This is most likely explained by a convention that the last day of the month was the 30th, regardless of whether there were actually 29 or 30 days in the month; on this basis the date is fully consistent with the Astronomical Diary. However, as will be seen below, there are grounds to doubt that Aristoboulos intended the date to be perfectly precise.

28 Daisios (Plutarch, Alexander 76.9, quoting the royal Diaries). The Diaries for the period of Alexander's death are also quoted by Arrian, Anabasis 7.24, but without dates.

There is an extensive debate on the authenticity and accuracy of the Diaries as quoted by Plutarch and Arrian, which I intend to review at a later time. For the moment, my own view is that they are most likely authentic, and that Plutarch's quotations are essentially accurate, but even if they are not authentic they were forged so soon after the event that we may safely assume that their format reflects that of an authentic set of Diaries and that the date given by Plutarch for the death of Alexander is therefore correct.

It is at first sight rather odd that two direct witnesses to the event who apparently used the same calendar should apparently differ by 2 days in their dating of it. E. Grzybek, Du calendrier macedonien au calendrier ptolémaïque 34, noted that at the siege of Tyre in 332 Alexander had redefined the last day of the month to be the 28th, i.e. that he had delayed the end of the month most likely by 1 day (Plutarch, Alexander 25.1-3). Grzybek suggests, and Depuydt accepts, that the court Diaries honored the retardation permanently. While this would certainly explain the discrepancy, it is, to my mind, a rather bizarre suggestion. One would expect that a single intercalated day would have been compensated for rather quickly in a lunar calendar, simply by making the next 30-day month a 29-day month instead.

A second possibility is that Aristoboulos and the Diaries used a different convention for the start of the day (and therefore the month) because their authors came from different regions of Greece and Macedon. Aristoboulos is said to have come from, or settled in, (the later) Cassandraeia, on the coast of Macedon; the Diaries are said by Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae 10.434b, to have been kept by Eumenes of Cardia, a city in the Thracian Chersonese, and Diodotus of Erythrae, a city in Ionia. In particular, Diodotus, an Ionian, may well have used a non-Macedonian system.

The Diaries use a dawn-based day. Plutarch describes the events of the day before those of the night when he groups them together (e.g. for 19 Daisios: Plutarch, Alexander 76.2 and for 24 Daisios: Plutarch, Alexander 76.6. This is a little less clear in Arrian's account, since it is undated, but again there is at least one instance (which C. A. Robinson, The Ephemerides of Alexander's Expedition, 67.26, aligns with 26 Daisios) where he lists the day and night in that order in relation to the deterioration in Alexander's condition.)

A. E. Samuel, Ptolemaic Chronology 43, argued that the internal evidence of the Diary extracts supports the view that the Diaries and Aristoboulos used different days, based on the method used to number days.

Aristoboulous gives the date of Alexanders death as the "30th" using a regular forward count (triakadi Daisiou mhnoV). However, Plutarch quotes the dates from the Diaries after the 20th in a decad format, which counts backwards down towards the end of the month (e.g. the 28th is th de trith fqinontoV -- the third day from the end of the month).

If this accurately represents the original document, it is contrary to ordinary Macedonian practice, as later documented from Egyptian papyri. A. E. Samuel, Ptolemaic Chronology 44, further cites Macedonian inscriptions showing a numeric, and therefore forward, count, as proof that the backwards count was also not Macedonian practice in Macedon itself:

SEG 12.373, dated 19 Gorpaios (Gorpaiou enathi epi deka) year 41 of Antigonos II = 242 (Amphipolis, found on Cos)

- IG X,2 1.3, dated 15 Daisios (Daisiou ie) year 35 of Philip V = 187 (Thessalonike)

- SEG 13.403, dated Audnaios (Audnaiou) <nn> year 42 of Philip V = 181 (Eordaea)

On this basis, A. E. Samuel, Ptolemaic Chronology 43 argued that the format is proof that the Diary does not represent Macedonian practice in counting days, and therefore cannot be trusted to represent Macedonian practice in marking the start of the day.

I have found the following additions to Samuel's Macedonian database which support his case:

SEG 48.782, dated 12 Embolimos(!) (Embolimou ib) year 16 of (Antigonus II?) = 269(?) (Dion)

- SEG 39.596, dated 15 Xandikos (Xa[ndikou pem]pthi [epi deka]) under Antigonus II(?) (Cassandreia)

- SEG 37.595, dated 15 Hyperberetaios (Uperbereta[i]ou pempthi epi d[e]ka) under Antigonus II(?) (Cassandreia)

- SEG 39.558, dated 15 Hyperberetaios ([Uperbere]taiou pempthi epi [deka]) (Cassandreia)

- Meletemata 22, Ep. Ap 19, dated 25? Appellaios (Appelliaou ke?) year 8 of (Philip V?) = 215(?) (Deriopus)

- SEG 45.764 = IG X 2, 2.1, dated 19 Panemos (Panhmo[u] qi) year 16 of Philip V(?) = 206 (Olivenos)

- SEG 39.606, dated 17 Hyperberetaios (Uperberetaiou iz), c. 204? (Crestonia)

- SEG 43.469, dated 7 Panemos (Panhmou z) year 39 of Philip V = 189 (Amphipolis).

However, there are at least two known examples of decad counting from Egypt which do use the same method used in the Diaries.

pLondon 7.1986, found in the Fayyum, is dated year 34 of Ptolemy II Daisiou trith fqinontoV (28 Daisios). H. I Bell, AfP 7 (1924) 17, who first published this papyrus, suggested that the unusual dating technique implied that the papyrus was from a geographic source not well represented in the papyri, specifically Alexandria. A. E. Samuel, Ptolemaic Chronology 43, who notes only this counterexample, argues that the method of counting days is connected with the fact that the witness list contains three probable Cyrenaicians (and a Roman), and concludes that the papyrus may therefore represent both non-Egyptian and non-Macedonian practice.

E. Breccia, Iscrizione greche e latine 164, not noted by Samuel, records a fragment of an Alexandrian inscription dated [thi pemp]thi fqinontoV. P. M. Fraser, CR ns 14 (1964) 316 at 317 n. 1, notes that its Alexandrian origin supports Bell's original proposal.

There are also Macedonian inscriptions, not known to Samuel, showing count of days apiontoV:

EAM 74, dated Gorpaiou [<lost> apionto]V, c. 4th/3rd century (Amphipolis)

- IG X,2 1.2, dated Olwiou enathi apiontoV (22 Loios) in year 7 of Antigonus III(?) (223) (Thessalonike),

- IG X,2 1.4, dated [Up]erberetaiou dekathi apiontoV (21 Hyperberetaios) year 53 of the provincial era (95) (Thessalonike).

A decad count of days apiontoV ("departing") is the most common form of backwards counting in Greek calendars, e.g. the Boeotian and Achaean calendars (A. E. Samuel, Greek and Roman Calendars, 69, 92), though the fqinontoV count is better known, due to its use in Attica (and almost nowhere else in Greece). That the apiontoV count is a backward count is clear from its name, but is also proven by ASAtene 41/42 161.6, a Coan inscription dated Hyacinthus 4 apiontoV and referring internally to Hyacinthus 6 and 5 apiontoV in that order.

Most importantly, the fqinontoV backwards count used in the Diaries is now documented in Macedon itself:

SEG 41.563, dated Dustrou ogdoh fqinon[toV] (23 Dystros), second half of the 4th century (Amphipolis)

This form was becoming obsolete in Athens in the late fourth century (W. K. Pritchett, CP 54 (1959) 151). It could even have been a court affectation under Alexander, reflecting his education under Aristotle, since Aelian, Varia Historia 3.23, records the date of a Diary entry on 28 Dios as trith met 'eikadoV, which was the incoming form in Athens.

On balance, it seems to me from this evidence most likely that Samuel is wrong, and that the backwards count used in the Diaries very probably did reflect a Macedonian practice, though possibly a rare one. Supposing nevertheless, for the sake of argument, that it is used in the Diaries because the court secretaries were not Macedonian, Samuel's further inference that the day is also non-Macedonian is more credible if the diary is a forgery than if it were genuine. It seems hard to believe that an authentic court diarist would not follow court practice on marking the start of the day, even if he used his native convention for counting days.

A dusk/dawn phase mismatch between the days of Diaries and Aristoboulos is in fact how K. J. Beloch, Griechische Geschichte IV.2 27, followed by A. E. Samuel, Ptolemaic Chronology, 42f., explained the discrepancy. If Alexander had died shortly after sunset of 10 June, the 28 Daisios of the Diaries would have began at dawn on 10 June while that of Aristoboulous would have begun at the previous dusk, so that his 29th (="30th"), aligned with the Babylonian day, was starting in the evening of the 28th of the Diaries. In effect, the two calendars are only 12 hours out of phase on this reconstruction. On this basis, the correct Macedonian date for Alexander's death was actually 29 Daisios, as was pointed out by A. E. Samuel, Ptolemaic Chronology, 42f.

However, with Alexander dying shortly before sunset on 11 June, this explanation becomes impossible, since the dates of the Diaries must be slipped by 1 day against the Julian and Babylonian calendars:

This solution retains the alignment of Aristoboulos' calendar against the Babylonian one. The apparent difficulty with it is that it means that the Daisios of the Diaries began 36 hours after the observation of the first crescent moon in Ayyaru and by Aristoboulos. Only 12 of these could be accounted for by a difference in the definition of the start of the day. However, the remaining 24 are within the normal range of difference for two observationally based lunar calendars. The calculated lunar phase at Babylon on 13 May 323, the start of Ayyaru, is 1.9%, while that on 14 May 323, the evening before the start of Daisios, is 5.6%. This difference is perhaps enough to explain a difference between the Macedonian and Babylonian day numbers, since the two were very probably based on lunar observations made by different observers, with the Babylonian observer being a professional astronomer at the temple of E-Sagila.

This explanation allows us to reconcile the 28 Daisios of the Diaries with the Babylonian 29 Ayyaru, and to retain 28 Daisios as the correct Macedonian date of Alexander's death. The difficulty remains of explaining the discrepancy between the Diaries and Aristoboulos. These are apparently both Macedonian dates, and so we would expect them to be based on the same observation of the new crescent moon, even if they did use different conventions for the start of the day. (For this reason, Depuydt's suggestion (WO 28 (1997) 117 at 127) that Aristoboulos, who was at the centre of court life, was using the Babylonian day numbers because he was in Babylon, strikes me as quite unlikely.) Given the 36-hour difference, the reason for it can no longer be a simple matter of a difference in the convention used for the start of the day.

There is perhaps one possibility, suggested by A. B. Bosworth, From Arrian to Alexander, 167. Aristoboulos is said to have written his memoirs at the age of 84 (Lucian, Makrobioi 22). While his dates are unknown, this must certainly have been several decades after the event. He may well simply have been writing from a slightly faulty memory, or, in an age that did not value precision about dates, he may simply have meant to indicate that Alexander died at the end of Daisios. It is notable that Plutarch gives both dates close together without commenting on the discrepancy, and that Arrian regards Aristoboulos as confirming the Diary account.

4 Pharmouthi (Eg.) = 13 June (ps. Callisthenes Codex A, and Armenian version). This was the generally accepted date before the Babylonian data became available. However, it cannot be directly reconciled with the lunar date.

E. Grzybek, Du calendrier macedonien au calendrier ptolémaïque 33 n. 42, supposing that Alexander had died in the evening of 10 June, suggested an MS corruption of "d" for "a" -- i.e. 1 Pharmouthi = 10 June.

However this would not explain a date of 11 June = 2 Pharmouthi.

A. J. Spalinger, Fs Kákósy 527, also accepting a date of 1 Pharmouthi = 10 June, proposed to explain the date of 4 Pharmouthi by marching through the hemerologies of the eastern calendars. He noted that 1 Pharmouthi = 27 March on the Alexandrian calendar, and that on the reformed Macedonian calendar used in Asia 27 March = 4 Artemisios, which, on the "Parthian" alignment between the Macedonian and Babylonian calendars prevailing at that time, corresponded to 4 Ayyaru. However in the earlier alignment between the Macedonian and Babylonian calendars Ayyaru = Daisios, which was then mapped back to Pharmouthi. Hence he proposes a sequence of conversions as follows:

1 Pharmouthi (Alexandria) => 4 Artemisios (Asia) => 4 Ayyaru (Babylon?) => 4 Daisios => 4 Pharmouthi

Spalinger himself is concerned that this proposal "may appear too convoluted for some" (!). It also fails because the correct date was 2 Pharmouthi not 1 Pharmouthi. (It might be thought that 27 March is 5 Artemisios on the Asian calendar, not 4 Artemisios, but the first day of a 31-day month was "Sebaste", with the following day accounted as the 1st).

L. Depuydt, WO 27 (1997) 117, proposes an explanation along somewhat similar lines, but one which has fewer conversions and is somewhat more plausible. Noting that Alexander died around the time of the new moon, Depuydt suggests that the translation to Pharmouthi is early, as the "new moon in Pharmouthi", but that the number "4" comes after the creation of the Alexandrian calendar. By that time Pharmouthi was roughly equivalent to April rather than July, so its new moon was the fourth of the Roman year. In support of this he notes that Codex B' has Alexander being born at the new moon of January (at sunrise) while the Armenian text has him born on 1 Tybi; in the Alexandrian calendar, Tybi aproximates to January.

"New moon" in Aprilis (ps. Callisthenes Codex B').

A. J. Spalinger, Fs Kákósy 527, supposing the date is 1 Aprilis, suggests a second series of multiple conversions paralleling the conversions he used to explain a transformation to 4 Pharmouthi:

1 Pharmouthi (Alexandria) => 1 Xanthikos (Gaza) => 1 Xanthikos (Antioch) => 1 Aprilis (Rome).

Again this fails if the correct original date was 2 Pharmouthi; also the correlation is to the "new moon" of Aprilis, not to 1 Aprilis.

For Depuydt, this is a result of exactly the same process used to explain the date of 4 Pharmouthi, but translates Pharmouthi to its Roman equivalent in the Alexandrian calendar.

6 Thargelion (Ath.) (Aelian, Varia Historia 2.25). This is part of a collage of events said to have happened on this date, including Alexander's birth and death, and his defeat and capture of Darius III at an unspecified battle, probably Issus.

Depuydt feels that the events are being forced onto the date, and that it does not have any actual historicity. While Aelian's account is certainly not completely accurate -- Alexander never captured Darius, though he did his household at Issus -- I'm not entirely happy with leaving the date at that point. Its really not an explanation, rather an excuse to avoid admitting a failure to find one. The Athenian date of Alexander's birth is well-documented to be 6 Hekatombaion (Plutarch, Alexander 3.1), so I wonder whether some other explanation isn't possible for associating 6 Thargelion with his death.

On the standard mapping of Athenian to Macedonian months as it appears to be applied by, say, Arrian, Thargelion corresponds to Daisios, which is correct. Moreover this Athenian year should not have been intercalary. As is well known, Greek festival calendars, including the Athenian calendar, could intercalate days, which would be compensated for by shortening months later. However, 6 Thargelion = 28/30 Daisios would be some 22-24 days late, which is a very late alignment for Daisios, requiring at least 22 days to be removed from Thargelion and Skirophorion if the archon year was to end on the correct new moon for Hekatombaion. It is hard to see how this would be possible.

Another possibility is that the date was originally 25 Thargelion = 6 days from the end of Thargelion, since the Athenians counted down the last decad of the month. On this scenario, the count down was lost before Aelian got the date. In that case, Thargelion was only running about 4 or 5 days late, which is relatively easy to compensate for.

In either case, and whatever its calendrical value may be, the date as we have it is not convertible to a specific Julian date. The datum underscores the difficulty of relying uncritically on Greek dates in the literary record.

While the Julian and Babylonian dates of Alexander's death can be regarded as certain, the Macedonian one is perhaps a little less so. Nevertheless, the view taken here is that the dates in Plutarch's version of the Diaries represent the contemporary record, and therefore that the Macedonian date of his death was 28 Daisios.

As to the date of Ptolemy's appointment, all we can say with certainty is that it was unlikely to have been later than c. 6 Panemos = 18 June 323. Ý

[6.1] The exact date that Ptolemy I regarded as the start of his rule in Egypt is difficult to determine. A priori, there are three plausible models :

He antedated his years to 1 Dios of his accession year, in which case his year 1 began in Dios 324.

- He postdated his years to 1 Dios of the year after his accession year, in which case his year 1 began in Dios 323.

- He used anniversary-based dating, in which case his year 1 began on 28 Daisios (i.e. the day of Alexander's death) or a few days later. Conventionally, this anniversary is dated as 29 Daisios.

Samuel believes that 29 Daisios was the actual Macedonian date of Alexander's death, although it is now clear that it really was 28 Daisios. But, supposing Ptolemy I used an anniversarial system of dating, it may well be that he dated the epoch of his regnal years from his appointment as satrap, which may well have occurred the following day; failing that, the date would be in early Panemos. Alternately he may have used the anniversary of his arrival in Egypt a few weeks later (which could explain the allocation of a year of Philip III in Porphyry).

Even if the anniversary date was the day after Alexander's death, however, it is unlikely that Ptolemy I accounted it as "29" Daisios. Since the Babylonian month Ayyaru 323 was a 29-day month, it is very likely that Daisios 323 was also a 29-day month, in which case the day after Alexander's death was not 29 Daisios but "30" Daisios. Even if Daisios 323 was for some reason a 30-day month, the date "29 Daisios" is still problematic since this date did not exist in 29-day Macedonian months. Supposing he dated his regnal years on this anniversary, the date he would have actually used is much more likely to have been 30 Daisios, in order to guarantee a fixed date for the new year in every year.

However, until evidence emerges to give a more precise date, Samuel's date may still be taken as a notional estimate, i.e. it should be understood to mean "28 Daisios or a little later".

Babylonian evidence allows us to rule out the second of these alternatives. The normal Babylonian convention was to postdate, by accounting the interval between the death of a king and the next 1 Nisanu as a tuppu year. This convention was changed in Babylonian texts of this period: year 1 of Philip III and Alexander IV began from the instant of their accession. This change can only reflect an adaptation to Macedonian practice. It follows that Macedonian regnal years were either antedated (option 1) or anniversarial (option 3).

The standard discussion is still A. E. Samuel, Ptolemaic Chronology 15ff. Samuel argued that Ptolemy I's regnal years were based on 29 Daisios. He presented arguments based on two data items: IG 14.1184 and two Elephantine papyri.

IG 14.1184 and the Death of Menander

IG 14.1184, an inscription (now lost) that dates the death of the Attic dramatist Menander, states: "Menander, son of Diopeithes of Cephissia, was born in the archonship of Sosigenes and died aged fifty-two in that of Philip in the 32nd year of the reign of Ptolemy Soter." Chronographically, the death of Menander is dated to his 32nd "Alexandrian" year in the Armenian edition of Eusebius, Chronicorum II (ed. Schoene) 118, and to his 33rd "Alexandrian" year in Jerome's adaptation of this chronicle. Samuel concluded that the archon year must have straddled Ptolemy I's 32nd and 33rd Macedonian year. The only way to reconcile this data is to suppose that year 1 = 323/2, so that year 32 = 292/1, starting somewhat in advance of the Athenian year = 292/1; Menander died either near the beginning or near the end of the archonship of Philip. If year 1 = 323/2, it must be based on a date of 29 Daisios.

This superficially attractive analysis is riddled with problems. Later treatments of IG 14.1184 are available in H. de Marcellus, ZPE 110 (1996) 69 and S. Schröder, ZPE 113 (1996) 35.

First, there is no reason to suppose that the date of Ptolemy I given by the inscription reflects his own regnal years. The inscription came from Rome, where it was the base of a herm with a portrait bust of Menander. It is dated to the early imperial period. It is perfectly possible, even likely, that the date given for Ptolemy I is a chronographic year, no different from those given by Eusebius.

Second, the inscription contains internal problems, not mentioned by Samuel. The archonship of Sosigenes fell in 342/1. The date of the archonship of Philip was uncertain at the time Samuel wrote, with different authorities arguing for 293/2 or 292/1; current opinion is 292/1, which is the date required by Samuel's analysis. Neither date is consistent with the age of Menander given as 52 years. Whatever the resolution of this difficulty, it does not inspire confidence in the inscription's strength as a synchronism.

Third, the difference of one Alexandrian year between the Armenian Eusebius and Jerome's transcription is not obviously an artefact of ambiguity in the relationship between Alexandrian years and archon years. The natural alternative, which Samuel does not consider, is that the discrepancy is due to corruption in the different MS tradition of the Jerome and the Armenian texts.

A. A. Mosshammer, The Chronicle of Eusebius and the Greek Chronographic Tradition, 24f., 39f. and 44 ff., emphasises that there are two distinct methods of organising the data in the MSS tradition. In what is now agreed to be the older tradition, represented in this transcription, the year numbers in various systems (Abrahamic, Olympic, Alexandrian etc.) are given in the left and right margins; Olympiads are listed before the first year of a tetrad, and only every tenth Abrahamic year is listed. The historical notices are placed in the main text, aligned to that the text falls after the year in which the event occurs. In the Armenian text, as in the more recent MSS of Jerome, the years are listed in a table that runs down the middle of the page, every Abrahamic year is given, and Olympiads are aligned with other years. The historical notices are placed to the left and the right, with the text of an extended notice apparently covering several years.

It is evident that the Armenian system is more prone to transcription errors that would change the chronology than that of Jerome, in that a historical notice can very easily become attached to the wrong year. In addition, there is a clear systematic error which has occured in the alignment of Olympiads. In Jerome's table, the start of a new Olympiad is proclaimed between two Alexandrian (or other) years, and applies to the following year. However, in the Armenian edition, the start of the Oympiad is given its own column, and is explicitly aligned with the preceding year, which was originally intended to be the last year of an Olympiad.

It is all too likely that the mismatch which is the basis for Samuel's argument is an artefact of such errors in the transmission of Eusebius' tables. If so, it cannot legitimately be used to infer the relationship of Ptolemy's Macedonian years to the systems used by his chronographers, and could not even if the date in IG 14.1184 was a Macedonian regnal year.

If Samuel's thesis is correct, then the mislaignment is due to a particular error in relating Athenian archon years to Alexandrian years. We would expect that the Alexandrian dates for other events in Greek and Ptolemaic history which are listed in both Jeromes' and the Armenian Eusebian tables should show a consistent relationship: they should either have the same Alexandrian dates or, occasionally, the date given in Jerome should be a year later than the date in the Armenian Eusebius.

The following table gives Alexandrian years according to both Jerome and the Armenian Eusebius for Greek and Ptolemaic events listed in both sources listed under the reigns of Ptolemy I and Ptolemy II, following the Schoene-Petermann edition (Eusebi Chronicorum II 114-119).

|

Alexandrian Year |

|

|

(Armenian) |

(Jerome) |

|

|

5 Ptolemy I |

4 Ptolemy I |

|

9 |

9 |

|

17 |

19 |

|

18 |

22 |

|

20 |

20 |

|

32 |

33 |

|

39 (= 3 Lysimachus) |

3 Ptolemy II |

|

2 Ptolemy II |

1 |

|

7 |

17 |

|

16 |

21 |

|

20 |

23 |

|

26 |

28 |

|

29 |

29 |

It is evident that there is no consistent relationship between dates in the two chronicles. Even clearly Ptolemaic events that one would expect to be dated by Alexandrian years in the ultimate source, such as the date of the building of the Pharos lighthouse, are different in the two chronicles. This being the case, there is no support in the chronicles for Samuel's proposed explanation of the discrepancy in the date of Menander's death.

In short, IG 14.1184 is useless for establishing the reference point for Ptolemy I's regnal years.

pEleph 3, pEleph 4 and the trofeia of Elaphion

Contemporary data for the start of the regnal year are given by two Greek papyri from year 41 (pEleph 3 (Artemisios) and pEleph 4 (Hyperberetaios) -- translations here). These two papyri concern transactions involving the same individuals, which gives us an opportunity to determine which one was written first. This would tell us whether Artemisios was before Hyperberetaios (favouring a Dios-based year) or Hyperberetaios was before Artemisios (favouring a Daisios-based year).

The details of the transactions in both cases involve a Syrian woman Elaphion, with a man described as her kurioV (guardian). She pays a third party a sum of money as trofeia (support) for herself. The third party is then enjoined from claiming trofeia again, or to reduce her to slavery (katadouloumenon), under penalty of a large fine.

The roles of the kurioV and the third party are assigned as follows:

pEleph 3 (Artemisios): kurioV: Pantarkes; payee: Antipator;

sum: 300 drachmae; penalty: 3,000 drachmae

pEleph 4 (Hyperberetaios): kurioV: Dion; payee: Pantarkes

sum: 400 drachmae; penalty: 10,000 drachmaeThe nature of the transaction is not clear. Samuel notes that several interpretations have been proposed, and the question has been discussed subsequently by Grzybek and Scholl. These interpretations affect the relative order of the papyri. The significant ones are:

O. Rubensohn, Elephantine-Papyri 27ff., supposes that Elaphion was a slave, or prostitute, and that the kurioV was effectively her owner or pimp. Each contract then marks purchase of control, first by Pantarkes from Antipator and then by Dion from Pantarkes -- and pEleph 3 predates pEleph 4.

Against this, A. E. Samuel, Ptolemaic Chronology 21, notes (a) that a slave cannot be a party to a contract (b) if she is being sold then why is she named as the payer? one would expect the new owner (apparently the kurioV) to be the payer (c) the nature of the "support" is very unclear in this scenario (d) the price is very high.

(a) and (b) seem to be valid and sufficient objections to me. (c) is the key issue to deciding the correct meaning (and sequence) and is discussed below.

(d) is a much weaker argument. In support, Samuel cites pCairZen 1.59003 dating from year 27 of Ptolemy II = 259/8 which records the purchase of an 8 year old girl for 50 drachma. W. L. Westermann, Upon Slavery in Ptolemaic Egypt 60f., lists all slave prices recorded in the Zenon papyri. In addition to Samuel's girl, we have: 112 drachmae for the purchase of a child (pCairZen 1.59010), 150 (sale price) for a man and 300 (purchase) for a woman (PSI 4.406), 133 drachmae 2 obol as valuation for a mother and daughter (pCairZen 3.59355). He also notes that pGrad 1 imposes sales tax of 20, 40 and 60 drachmae in an apparently special sale. Since pCol inv 480 = pCol 1.1 imposes taxes at a rate of approximately 20 drachmae per mina, he infers sales prices of 1, 2 or 3 mina = 100, 200 or 300 drachmae, though this last document is admittedly somewhat later, dated to 198/7. However the net conclusion is clear: the individual sums named in the Elephantine papyri are not out of line for Ptolemaic slave prices, although they are on the high side.

These are a limited number of data points and they show high variance. A statistically significant database is provided by approximately 1,000 manumission decrees recorded at Delphi in the last two centuries, analysed by K. Hopkins & P. J. Roscoe, in K. Hopkins, Conquerors and Slaves 158ff. (a promised study on Thessalian manumission decrees by the same authors appears never to have materialised). Unfortunately Hopkins & Roscoe only give mean price data, variance is not considered.

In the early second century, the mean manumission price of a female slave at Delphi was 376 drachmae. The Delphic prices increased by about 25% per century, which suggests that at the beginning of third century an adult female slave cost about 300 Delphic drachmae. K. Hopkins & P. J. Roscoe, in K. Hopkins, Conquerors and Slaves 160 n. 48, estimate the Delphic drachma at about 70% of the Athenian drachma, however they have it backwards. A drachma was 0.01 silver mina. Delphi used the Aeginitan mina of c. 628 grams, while the Attic mina weighed only 430 grams (E. Babelon, Traité des monnaies grecque et romains, I 491f.)), i.e. 1 Delphic drachma = 1.4 Attic drachma, making the estimated female slave price = c. 420 Attic drachmae. G. le Rider & F. de Callataÿ, Les Seleucides et les Ptolemées 143, note that Attic drachmae were exchanged for Ptolemaic drachmae at par, but that the Ptolemaic drachmae weighed only 81% of an Attic drachma. Assuming this differential was reflected in prices, the Attic equivalent of 300 Ptolemaic drachmae is c. 240 Attic drachmae = c. 170 Delphic drachmae.

Also, iBeroia 45 = SEG XII 314, a Macedonian manumission decree dated year 27 Demetrius (probably Demetrius I, i.e. c. 290 (E. Grzybek, Arch. Mak. 5 (1993) 521), though Demetrius II, i.e. c. 235, is also argued), values a female slave at 25 gold staters. Since IG XII 7.69, from about this period, equates Alexandrian, Demetrian and Attic drachmae, this can safely be equated to 500 Attic and Alexandrian drachmae.

On this basis, Elaphion's trofeia was cheap compared to slave prices. However, if one exchanges Delphic drachmae with Ptolemaic drachmae at par, the prices are comparable.

In short, Samuel's argument that 300 or 400 drachmae is a high valuation for a female slave does not seem to be correct.

J. Partsch, Greichisches Bürgerschaftsrecht I 351 n. 5., supposes that that Elaphion had been freed on condition that she give support ("trofeia") to her previous owners, and that the purchase quits her of this obligation. He assumes Rubensohn's ordering.

Against this, A. E. Samuel, Ptolemaic Chronology 21, notes (a) that the contracts contain no indication that Elaphion had ever been a slave (b) that the theory does not explain why Pantarkes is the kurioV in pEleph 3 but payee in pEleph 4 (c) how Elaphion was able to raise 700 drachmae, 300 or 400 of which were raised in 6 months.

The most recent commentary I have found, R. Scholl, Corpus der ptolemäischen Sklaventexte 141f., returns to Partsch's theory. In support of Elaphion's slave status, he notes that trofeia is well-documented as a term for buying manumission, that "Syrian" was almost synonymous with "slave" in documents of this date, to the extent that the majority of imported slaves were Syrian, and that "Elaphion" is documented as a slave-name (pCairZen 3.59333). A contract in which Elaphion is buying her freedom well explains the katadouloumenon provisions. On this explanation, pEleph 3 is the earlier of the two papyri, since Pantarkes is her kurioV (who here must be "joint owner") and is not paid off till pEleph 4. Scholl suggests that, alternatively, she was considered free after the first payment but had to make the payment in two parts -- the large amount of money involved (700 drachmae) being simply the high price of freedom. He notes that the signature of Nikagoras, the suggrafofylax, is only affixed to pEleph 4, which he supposes indicates that the transaction was concluded by that contract. Again, it would follow that pEleph 3 predates pEleph 4.

While neither Grzybek nor Scholl mention Samuel's objections, Scholl makes a reasonable circumstantial case against his objection (a): the contract does contain indications that could (but need not) be indications of former slave slave status for Elaphion. He is less successful in overcoming objection (b). On Scholl's theory, Pantarkes is kurioV in pEleph 3 because he still maintained rights over Elaphion, rights which were acquitted in pEleph 4. But the contract wording does not require this interpretation, and more importantly it leaves the role of Dion completely unexplained, as Scholl himself recognises, since pEleph 4 is supposed to mark Elaphion's final transition to free status, yet Dion plays exactly the same role in pEleph 4 that Pantarkes played in pEleph 3. Finally, he does not address (c) at all: Samuel's question is not why the sum is so large but how a slave -- a female slave -- could raise so much money.

Scholl raises an important point by noting that only pEleph 4 is signed by Nikagoras, the keeper of the contract. But I think he has it backwards. Contracts are normally signed and sealed when they are entered into, not when their execution is concluded. The fact that Nikagoras' signature and seal is placed on pEleph 4, not pEleph 3, is (to my mind) sufficient evidence in and of itself that pEleph 4 is the primary contract and therefore the earlier one. It was not necessary for him to sign pEleph 3 since he was already the contract keeper for Elaphion.

A. E. Samuel, Ptolemaic Chronology 23, notes that Elaphion is the payer, that the sums of money are large, and that there is no sign of a husband or relative. He also noted that in Ptolemaic peregrine law, a woman required the assistance of a kurioV when she was a party to a formal contract drawn up by a suggrafofylax (R. Taubenschlag, The Law of Greco-Roman Egypt in the Light of the Papyri, 175). In theory, the kurioV is acting as her guardian, though in practice he would be her agent in such a context. He concludes that Elaphion is a wealthy woman, possibly running a business connected with the Elephantine garrison. Finally, he notes that Pantarkes appears in both documents, once as kurioV and once as payee. Thus, Pantarkes' relationship to Elaphion certainly changed between the two contracts and it is most likely that the contracts are themselves the instruments of that change.

Samuel concludes that the trofeia acquired by the transactions must be understood as including the services of a kurioV. Even when acquiring or discharging such services, Elaphion must be still assisted in such transaction by a kurioV, who must then be the outgoing kurioV who is, therefore, discharged by the same transaction. On this interpretation, pEleph 4 must be the earlier of the 2 papyri, in which she is engaging the services of Pantarkes, paying him in advance, and discharging Dion. In pEleph 3 she is then similarly engaging the services of Antipator and discharging Pantarkes.

Against this, E. Grzybek, ZPE 76 (1989) 206, notes (a) that it is highly unlikely in Hellenistic society that a woman would be able to engage in commerce at such a level of cashflow and (b) Samuel's interpretation of trofeia is equally unlikely. Scholl ignores Samuel's discussion.

I don't find either objection to be more than prejudice. In medieval Islamic society both slaves and women with sufficient strength of character and the right connections were able to make their way in the world, even if they were unusual. Contract law would have to be adapted to them, and Taubenschlag's comments indicate that in fact it was. The notion of trofeia as "service" as an extension of "support" seems not unreasonable; a crux of Grzybek's own proposal is that it could represent a dowry, which purchased the support of the family a woman married into. Indeed, it may be that Elaphion was wealthy not because she was engaged in commerce but by inheritance; Samuel's reconstruction would be just as viable.

M. Passehl, pers. comm., has proposed that Samuel is essentially correct in his understanding of the formal role of the kurioV, but that the contracts are not simultaneously engaging a new kurioV and discharging an old one. Rather, they are paying off an old kurioV in arrears for services rendered after the new kurioV has already been hired. This would allow pEleph 3 to be the earlier of the two contracts.

However, the contracts are formally concerned with payment of trofeia, which usually refers to support that will be rendered in the future. Moreover, on this explanation we would expect to see two separate contracts on essentially the same date, one for engagement of the new kurioV followed by one for discharge of the old kurioV, and we would still expect to see an earlier contract engaging the old kurioV. In other words, Passehl's scenario postulates the existence of documents not in evidence.

E. Grzybek, ZPE 76 (1989) 206, sees the trofeia as a form of dowry, and regards Pantarkes as having literally been Elaphion's guardian. In effect, the payment to Antipator was made from the 400 drachmae that had been paid to Pantarkes, who made 100 drachmae by acting as Elaphion's guardian for 6 or 7 months. However, he stresses that this explanation preserves Samuel's chronological interpretation of the data. This interpretation is followed in the most recent publication of these papyri by J. J. Farber in B. Porten et al., The Elephantine Papyri in English, 414 (D4) n. 1.

Against this, R. Scholl, Corpus der ptolemäischen Sklaventexte 141f. notes (a) that the papyri give no hint that the 300 drachmae paid to Antipator comes out of the 400 previously paid to Pantarkes, and (b) that Grzybek ignores, and his explanation cannot explain, the provisions against claiming trofeia in the future.

While I think objection (a) is rather weak, (b) seems to me to be decisive. In essence, Grzybek's theory implies that the contract is a receipt with a built-in penalty for challenging its authenticity. The notion that a concubine-in-waiting was transferred between at least three successive guardians also seems to me (though apparently not to Farber) rather farfetched. One must wonder what was taking her eventual partner so long.

I am hardly an expert in Ptolemaic contract law. Nevertheless, Samuel's explanation seems easily the most reasonable to me of the ones offered to date. Except in Grzybek's explanation, Elaphion must have access to large funds, regardless of whether or not she was formally a slave. But I doubt that she was, despite Scholl's point that the contract uses terminology found in other manumission contracts. The fact that Pantarkes and Dion both play the role of kurioV indicates to me that they had the same relationship to her, which is difficult to explain if the contracts were partly about the purchase of her freedom from Pantarkes. Whatever the nature of the transactions, Elaphion is equally free (or unfree) in both of them.

The key question is the temporal implication of purchasing trofeia. A detailed discussion is presented in W. L. Westermann, CP 40 (1945) 1. In manumission decrees, a freed slave often remains an indentured servant to the former master, in return for trofeia -- support -- meaning, essentially, food and board, the purchase of which is covered by the manumission price. Similarly, it was provided as support for wetnurses, as sustenance compensation for support for detained runaway slaves before they could be returned to their owners. Westermann notes a set of Claudian papyri from Tebtunis which are contracts for trofeia, distinguishing between simple maintenance and slave maintenance; he notes that the former is for free men (or women); the payments are prepayments.

In short, while the exact significance of trofeia depends on context, it is generally maintenance support that is paid for in advance. Thus in pEleph 4 Elaphion is paying for trofeia to be supplied by Pantarkes, and in pEleph 3 she is paying for trofeia to be supplied by Antipator. The provisions against reduction to slavery suggest that she is a servant, possibly a freedwoman, but they do not indicate that her status is changing as a result of these transactions. Samuel's temporal analysis is essentially correct, even if his view of Elaphion's status is probably wrong.

The net result of all this is that Hyperberetaios in year 41 (pEleph 4) was most likely, though not certainly, before Artemisios of year 41 (pEleph 3). Therefore the start of Ptolemy I's Macedonian years was between Artemisios and Hyperberetaios, which excludes any scenario in which his years started in Dios. Samuel concludes that they started on the anniversary of Alexander's death, i.e. (for him) on 29 Daisios.

The Macedonian date of the Ptolemaieia

L. A. Nerwinski, The Foundation Date of the Panhellenic Ptolemaea 104ff., introduced a new line of argument on this question. While Nerwinski's analysis of the date of the Ptolemaieia assumed Samuel's conclusion that the regnal year of Ptolemy I was based on 29 Daisios, his argument is largely independent of that assumption.

C. C. Edgar, Mélanges Maspero II 53, had noted that several of the Zenon papyri referred to a pentaeteris -- a quadrennial festival -- in Alexandria. PRyl 4.562, dated 26 Payni year 35 (Eg.) = 16 August 251 = c. 22 Daisios (Mac.), is concerned with finding a billet for some cavalrymen who are apparently en route to Alexandria for the pentaeteris. PSI 4.364, dated 8 Loios year 35 (Mac.) = c. 30 September 251, refers to a victory of Zenon's brother Dionysos in the Ptolemaieia held at the town of Hiera Nesos, in the Fayum. Equating the Alexandrian pentaeteris with the Ptolemaieia, and assuming that its celebration was governed by the Macedonian calendar, Edgar concluded that the Ptolemaieia fell on a date between 22 Daisios and 8 Loios. Nerwinski extended this argument by noting that the only known date which is significant for Ptolemy I that fell in this range is 29 Daisios, and, since the festival is a Ptolemaieia it is unlikely that the significance of this date is merely as an anniversary of the death of Alexander. Accordingly, he holds that the date of the Ptolemaieia is based on the regnal years of Ptolemy I, and these were based on 29 Daisios.

He spends several pages justifying the assumptions given above. To summarise these justifications briefly:

With the possible exception of the Arsinoeia (but see here), all known Alexandrian festivals were governed by the Macedonian calendar, therefore the Ptolemaieia was also celebrated on the Macedonian calendar.

Further, SEG 28.60 = SEG 29.102, the Athenian decree of honour of Kallias of Sphettos (T. L. Shear, Kallias of Sphettos and the Revolt of Athens in 286), shows that the first Ptolemaieia, in the late 280s or early 270s, was celebrated shortly before the date of the Panathenia, which was celebrated on 28 Hekatombaion (Ath.) (c. July/August). The pentaeteris of 251/0 was celebrated 1-2 months later. This matches the drift in the Macedonian calendar over this period.

This view is disputed by R A Hazzard, who agrees that the Ptolemaieia was initially regulated according to the Macedonian calendar, but supposes that starting in 262 it was regulated by the achronycal rising of Canopus on 25 January, i.e. that it was effectively regulated according to a Julian calendar. On this thory see below.

The Ptolemaieia was defined as isolympic (=pentaeteric) in the Decree of the Islanders (SIG3 390 = IG XII.7.506). All other known Alexandrian festivals can be shown to be annual, or probably so.

This view is disputed by P. M. Fraser and E. E. Rice. both of whom claim that there is evidence of a second pentaeteric festival. P. M. Fraser, Ptolemaic Alexandria II 380 n. 326, draws attention to pHal 1 ll. 262-3, which lists three Alexandrian festivals, the [name lost] festival, the Basilea and the Ptolemaieia. The original editors had restored a festival of Alexander, but this is otherwise undocumented and doesn't fit syntactically in the most natural form ("Alexandreia"). Fraser suggests instead "the [pentaeteric] festival", thus distinguishing it from the Ptolemaieia.

L. A. Nerwinski, The Foundation Date of the Panhellenic Ptolemaea 110ff. raised the same objections to an "Alexandreia" but noted (p 115) that pOxy 27.2645, a fragment of a work of Satyrus on the Demes of Alexandria, describes an annual festival in the suburb of Eleusis. Nerwinski shows that the lacuna can reasonably be restored as "the [Eleusinian] festival".

The other arguments for a second pentaeteric festival depend on an extract (Athenaeus 5.197Dff.) from a lost work of Kallixeinos of Rhodes which describes a spectacular grand procession for a pentaeteric festival under Ptolemy II. Neither Kallixeinos nor Athenaeus names the festival. Most modern scholars believe it is an account of a Ptolemaieia. The following arguments are presented against this view:

P. M. Fraser, BCH 78 (1954) 49 at 57-8 n. 3, and Ptolemaic Alexandria II 379 n. 321 and 381 n. 335 notes that Kallixeinos refers to the "records of the pentaeterides", and argues that this phrase is most reasonably interpreted as records of different pentaeteric festivals.

However, he himself admits (Ptolemaic Alexandria II 379 n. 321) the possibility that these records could have been records of successive instances of the pentaeteris.

P. M. Fraser, Ptolemaic Alexandria I 231, notes that the figure of "Pentaeteris" in Kallixeinos' account appears in the Dionysiac segment of the procession, implying that the pentaeteric festival reported by Kallixeinos is a Dionysiac festival, not the Ptolemaieia.

Theocritus, Idylls 17.112-4, attests that there was a Dionysia in Alexandria distinct from the Ptolemaieia. However, L. A. Nerwinski, The Foundation Date of the Panhellenic Ptolemaea 10f., correctly notes that the figure of "Eniatous" (year) which appears in the same segment of the procession as the figure of "Pentaeteris", is much more clearly identifiable as a Dionysiac figure, implying that the Dionysia was an annual festival.

Further, it is unclear to me why the Ptolemaieia could not have been a Dionysiac festival, since OGIS 54 attests that Ptolemy I was supposedly descended from Dionysos on his mother's side. In particular, the Ptolemaieia could have been a greater Dionysia, analogous to the annual and the pentaeteric Panathenaieias. This would explain the presence of figures of both an Eniatous and a Pentaeteris in the procession.

E. E. Rice, The Grand Procession of Ptolemy Philadelphus 185f., argues that the grand procession cannot be the Ptolemaieia because Kallixeinos' account, which addresses the highlights of the procession (e.g. Athenaeus 5.201B, F), does not include "any particularly marvellous honours given to Soter", which is hard to believe if the festival was in his honour.

This is disputable on two grounds. First, R. A. Hazzard, Imagination of a Monarchy 67ff., notes that there were significant honours for Ptolemy I: a division of the parade was named for the Theoi Soteres, they were honoured with precincts at Dodona and statues in gilt chariots, and a crown worth 10,000 gold pieces was carried in the thone of Ptolemy I. Second, Hazzard reasonably argues that the procession reported by Kallixeinos is as much propaganda for the Ptolemaic dynasty as it is a celebration specifically in honour of Ptolemy I. Certainly we would expect the Ptolemaieia to have this aspect.

All in all, the arguments for evidence of a second paentaeteric festival seem to me to be less than convincing. While the hypothesis cannot be positively excluded, it seems unnecessary to explain the data we have.

While the Alexandrian pentaeteric festival is never referred to explicitly as the Ptolemaieia in the Zenon papyri, Nerwinski argues that this can be explained by the need to distinguish it from the local Ptolemaieias such as that at Hiera Nesos, which may have occurred at a different rate, e.g. annually, and possibly not at precisely the same time, due to the difficulty of synchronising the Macedonian calendar thoughout the country. However, in the year of the pentaeteric Ptolemaieia, we can expect local celebrations to have been held at almost or exactly the same time. Thus, even if there is a distinction between the local and Alexandrian festivals, the existence of the Ptolemaieia at Hiera Nesos indicates that the (near) concurrent Alexandrian festival was the pentaeteric Ptolemaieia.

The major apparent problem with Nerwinski's analysis is Kallixeinos' comment that the festival he describes took place in winter (Athenaeus 5.196D). If this is correct, then there must have been a second pentaeteric festival, which is either the festival described by Kallixeinos itself or the pentaeteric festival whose dates were limited by the bounds which Nerwinski established.

L. A. Nerwinski, The Foundation Date of the Panhellenic Ptolemaea 131ff., notes that the comment is part of an explanation of the availability of a large variety of flowers, and so is a comment made by Kallixeinos, not a quote from the Records of the Penteterides. Further, Kallixeinos says that the festival took place in winter tote ("at that time"), meaning that its date did not fall in winter in his own day. Nerwinski argues that the comment can be explained if Kallixeinos wrote in the late second century or in the first century BC, at which time 29 Daisios = 29 Pharmouthi, a date in mid May. At this time his knowledge of the relationship between the Macedonian and Egyptian calendar would most likely reflect the alignment under the middle Ptolemies, for whom 29 Daisios = 29 Choaik, a date in mid January, rather than an accurate knowledge of the solar alignment of the Macedonian calendar under Ptolemy II.

Two other recent analyses of the date of the Ptolemaieia, neither taking notice of Nerwinski's thesis, have taken an entirely different approach. Both assume that the grand procession is the Ptolemaieia, and that it did indeed take place in winter. Both are based on the assumption that the mention of the figures of the morning star, which opened the procession, and the evening star, which closed it (Athenaeus 5.197D), have astronomical significance, and therefore indicate the Julian date of the Ptolemaieia.

V. Foertmeyer, Historia 37 (1988) 90, argues on circumstantial grounds that the festival concerned must have taken place in the 270s and was the first Ptolemaieia. She further argues that the figures of the morning and evening stars imply that the procession lasted from the last appearance of Venus as morning star to its first as evening star -- a period of around two months. She argues that in view of the size and magnificence of the festival, such a prolonged celebration is not impossible. Her calculations show that the only year in the 270s which meets these conditions in winter is 275/4 -- a year on which a Ptolemaieia should have occurred. Hence she concludes that the Ptolemaieia described by Kallixeinos is that of 275/4.

R. A. Hazzard & M. P. V. Fitzgerald, JRASC 85 (1991) 6, with additional commentary in R. A. Hazzard, Imagination of a Monarchy 28ff., interpreted the same data in a different way. Hazzard supposes that the figure of the morning star shows the morning star as patron of the current Ptolemaieia, while the figure of the evening star, closing the procession, is looking forward to the next Ptolemaieia. His view is that this symbolism exploits the 8-year cycle of Venus, which has the property that Venus will appear as morning and evening stars on most dates four years apart. As to the specific date, Hazzard adduces late evidence that the star Canopus was renamed after Ptolemy I, and supposes that the start was used to set the date of the Ptolemaieia in order to counteract the draft of the Macedonian calendar. On various circumstantial grounds, Hazzard argues that this alignment was first used for the Ptolemaieia of 262. Fitzgerald's calculations showed that the acronychal rising of Canopus at Alexandria occurred on 25 January (Julian) every four years, and that in 262 it coincided with the first rising of Venus as the morning star. Hence Hazzard concluded that the Ptolemaieia was held on 25 January (Julian) from 262 onwards, and proposed that it had previously marked the death of Ptolemy I on or around 25 Dystros, except for the first occurrence in 282.

Hazzard cheekily remarks (Imagination of a Monarchy, 4 and n. 8): "No one has challenged this new dating. [Because refutation would require a knowledge of astrophysics, no classical scholar has made the attempt.]" But this is not true. The problem with his argument, as with Foertmeyer's, is not the astrophysics, which is unarguable in both cases. The problem is the papyrological and literary analysis.

Both authors accept that the winter date comes from the contemporary source of the Records of Pentaeterides. Neither considered the possibility, argued by Nerwinski, that it is a comment by Kallixeinos himself reflecting the circumstances of his own times. In Hazzard's case, this is despite the fact that he also argues at some length (R. A. Hazzard, Imagination of a Monarchy, 62ff), that Kallixeinos lived in the late second century or even later, noting:

Kallixeinos twice refers to Ptolemy IV by epiklesis as Ptolemy Philopator (Athenaeus 5.203E and Athenaeus 5.204D), indicating that he was not the ruling monarch when Kallixeinos wrote.

- He refers to Ptolemy II as Philadelphus (Athenaeus 5.203B and Athenaeus 5.203C). This title is not documented in the papyri before 165.

- His description of the Dionysiac shrine on the river barge mentioned portrait statues of the rulers' relatives (oi twn basileiV suggeneiaV -- Athenaeus 5.205F). This is a formal Ptolemaic court title of the late second and first centuries BC, and the replacement of the phrase basileuV kai basilissa by basileiV is only attested after Cleopatra III was made coruler in 140/39.

Earlier analyses, most recently E. E. Rice, The Grand Procession of Ptolemy Philadelphus, 164ff, had noted only the first point, and had then become entangled in esoteric and ultimately indeterminable arguments about whether or not the grammatical structure and style of Kallixeinos' descriptions of the parade implied that he had personally witnessed it and was writing as an old man. It seems to me that Hazzard's arguments are based on hard comparative data, and his conclusion is sound.

Evidently, this result is entirely consistent with Nerwinski's view that Kallixeinos wrote after the final Macedonian calendar reform in Egypt, which is first documented in 118. However, Hazzard in R. A. Hazzard & M. P. V. Fitzgerald, in JRASC 85 (1991) 6 at 20 n. 5 chooses to interpret Kallixeinos' statement that the festival was held in winter tote ("at that time") as meaning that the festival had previously been held on a different time.

This accepts that the word is in fact a comment by Kallixeinos, but it overreads its meaning to suit Hazzard's theory, and supposes that Kallixeinos, well over a century after the event, had some means of knowing what season the festival actually occured in its various instances.

F. W. Walbank, SCI 15 (1996) 119 at 121f. n. 16, notes that Athenaeus 5.204D does not specify that the festival started at the time that the morning star appeared (i.e. a specific sychronism), but that it started at the time that the morning star appears (i.e. a general statement), and similarly that the appearance of the figure of the evening star was timed for the time when the evening star would appear in the sky -- i.e. twilight. He cites the analagous example of Polybius 30.25.15, describing the figures of night, day, and dawn and midday in the great procession of Antiochus IV at Daphne in 166. He concludes that the figures were simply meant to dramatically open and close the procession at dawn and dusk, and had no special astronomical significance.

The argument seems fair enough to me.

Only Hazzard (Imagination of a Monarchy, 32f.) considers the papyrological evidence cited by Edgar and Nerwinski. Although he reviews Edgar's argument in detail, he only notes that PSI 4.364, which had provided Edgar with a terminus ante quem of 8 Loios year 35 (Mac.) = c. 30 September 251 for the Ptolemaieia of that year, was used by Edgar to identify the Pentaeteris with the Ptolemaieia. However, he accepts Edgar's terminus post quem of pRyl 4.562, 26 Payni year 35 (Eg.) = 16 August 251 = c. 22 Daisios (Mac.). In order to reconcile this with his view that the Ptolemaieia was held on the acronychal rising of Canopus = 25 January 250, he supposes that the billeting order for some travelling cavalrymen reported in pRyl 4.562 had to be made weeks or months ahead of the planned travel, because travel was slow and arduous. Edgar's view was that the papyrus indicated an imminent departure from the Fayyum, and he found it incredible that they would stay in Alexandria very long before the start of the Ptolemaieia.

I agree with Edgar. Zenon was in regular contact with Alexandria. There is no way it would take 5 months for the necessary travel, and no reason to believe that billets had to be arranged so long in advance. Hazzard's apparent suppression of the critical evidence of the date of PSI 4.364 is a baffling omission.

Hazzard adduces another item not known to Edgar or Nerwinski: pHeid 6.362, which includes a directive dated 21 Choiak year 21 (Ptolemy III, on prosopographical grounds) = 6 February 226 forbidding further export of calves from a nome since they were needed for the Pentaeteris. He supposes that the Ptolemaieia concerned was already in progress or just about to commence, sliding over the fact that the achronycal Canopic rising of 226 was already nearly two weeks in the past. But it seems more reasonable to interpret this as advance planning for an event due to occur some time later, since the cattle involved would also have to be brought to Alexandria.

This datum is also apparently a problem for Nerwinski's interpretation of the pentaeteric cycle, since the expected occurrence is between 22 Daisios and 8 Loios 227/6 = c. 18 October 227 - c. 2 January 226. From pGurob 2, we have 16 Dystros year 21 = 19 Payni = 2 August 226, corresponding to the new moon of 20 July. Working backwards this gives us 22 Daisios - 8 Loios year 21 (Mac.) = c. 18 November 227 - c. 2 January 226, with no intercalations before Dystros, or c. 20 October - 3 December 227, with an intercalation before Dystros. One possibility is that Ptolemy III changed the date of the Ptolemaieia to suit his own purposes. His own accession date of 25 Dios fell c. 16 April 226 in year 21, which is a little over 2 months after the date of the order.

Notwithstanding the difficulty raised by pHeid 6.362, and whatever the uncertain significance of the Morning and Evening star figures in the procession reported by Kalleixenos, or the actual year of this particular procession, Nerwinski has much the better case for determining its calendar date, as far as I can see. I therefore concur with him that the Ptolemaieia was indeed held between late Daisios and early Loios under Ptolemy II.

The weakness in using this result to establish the epoch of Ptolemy I's regnal year is Nerwinski's assumption that the only possible date of significance to Ptolemy I between 22 Daisios and 8 Loios was 29 Daisios.

Since he also thinks that the first Ptolemaieia was held on 29 Daisios = 10 May 282, he concludes, with Hazzard, that Ptolemy I must have died several months earlier, possibly as early as 25 Dystros, as proposed by L. Koenen, Eine agonistiche Inschrift aus Ägypten und frühptolemäische Königsfeste, 52. If this were correct then his conclusion that the Ptolemaieia was held on the start of Ptolemy I's regnal year could well follow. But it is more likely that if the first Ptolemaieia was held in 282, before the Panathenea on 28 Hekatombaion (Ath.), this would favour a death date in late summer of 283, which in turn would require a Dios-based regnal year.

Alternatively, if Samuel has correctly interpreted the evidence of pEleph 3 and pEleph 4, and the first Ptolemaieia was held in 278, as is held here, this would suggest that Ptolemy I died between Artemisios (or perhaps slightly before) and the end of that regnal year. In this case, the Ptolemaieia could well have been held on the anniversary of his death, except possibly the first Ptolemaieia, if indeed that was held in 282. On the other hand, the same argument supports the view that his regnal year began on 29 Daisios, so even if the Ptolemaieia was held on the anniversary of his death rather than that of his accession, it would still follow that his regnal year began on 29 Daisios -- but the date of the Ptolemaieia would no longer be an independent argument for this result.

However, there are other possibilities than the regnal year or the anniversary of the date of death. It may be that the Ptolemaieia marked the birthday of Ptolemy I, which is not (yet) known, or the anniversary of his adoption of the title of basileuV (e.g. after the siege of Rhodes). In these cases, the date of the Ptolemaieia need not have any relationship at all to the start of his regnal year. So, Nerwinski's analysis, while both suggestive of, and consistent with, a date of 29 Daisios, does not prove it correct.

The Macedonian Regnal Years of Ptolemy I and Alexander IV