Ptolemy XII

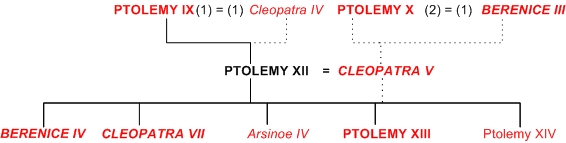

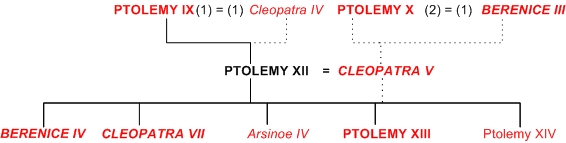

Ptolemy XII Neos Dionysos Philopator Philadelphos1 also known as Ptolemy Nothus2 and Ptolemy Auletes3, king of Egypt, son of Ptolemy IX4 by an unnamed mother, possibly a concubine but here identified as Cleopatra IV5, born either c. 98 or (preferred here) late 1176, probably in Cyprus7, here identified with the son of Ptolemy IX who was eponymous priest in year 9 = 109/88, and with one of the two children left behind in Alexandria when his father was expelled in 1079, who was probably sent to Cos in 10310, whence he was probably captured by Mithridates VI of Pontus in spring 8811; returned to Egypt as king probably shortly before 13 Pharmouthi year 2 (of Berenice III) = year 1 = 22 April 8012 with Cleopatra V as coregent13, incorporated in the dynastic cult with her as the Father-loving and Brother-loving Gods: Qeoi FilopatoreV kai Filadelfoi14, crowned in Memphis 7615, removed Cleopatra V as coregent between 4 Mesore year 12 = 8 August and 24 Phaophi year 13 = 1 November 6916, probably victor in the pair at the Basileia at Lebedeia probably before c. 6516.1, not deposed in 6516.2 or 6316.3, deposed by Cleopatra VI (here identified with Cleopatra V), and Berenice IV17 in c. June 5818, restored in February 5519, probably did not associate Ptolemy XIII and/or Cleopatra VII as coregents in early year 30 = 52/120, died of disease February/March 5121, succeeded by Ptolemy XIII and Cleopatra VII22.

Ptolemy XII's titles as king of Egypt were firstly23:

Horus Hwnw-nfr bnr-mrwt Tnj-sw-nbtsic-rxyt-Hna-kA.f dwA.n.f-xnmw-Sps-r-Szp-n.f-xa(t)-m-nsw

snsn.n-sHnw-m-Haaw-mj-ND-jt.f THn-msw(t)-Hr-nst-jt.f-mj-@r-kA-nxt jty-psD-m-&Amrj-mj-@pw-anx

rdj-n.f-HAbw-sd-aSAw-wrw-mj-PtH-&ATnn-jt-nTrw24

Two Ladies wr-pHtj xntS-nHH nfr-jb wTz-nfrw-mj-+Hwtj-aA-aA25

Golden Horus aA-jb jty nb-onw-nxt-mj-zA-Ast26

Throne Name jwa-n-pA-nTr-nHm stp-n-PtH jrj-MAat-n-Ra sxm-anx-Jmn27

Son of Re ptwlmjs anx-Dt mrj-PtH-Ast28Ptolemy XII alternately used certain titles as follows:29

Two Ladies wr-pHtj xntS-nHH smn-hpw-mj-+Hwtj-aA-aA30

Golden Horus aA-jb mrj-nTrw-BAot ity-mj-Ra HoA-WADtj31Ptolemy XII was engaged to Mithridatis or Nyssa, daughter of Mithridates VI king of Pontus, probably in 8032, and had one known marriage33, to Cleopatra V in or before Tybi year 2 = January 7934, here identified as a daughter of Ptolemy X35 probably by Berenice III36, by whom he probably had five37 children: Berenice IV38, Cleopatra VII, Arsinoe IV, Ptolemy XIII and Ptolemy XIV39.

[1] PP VI 14558. Gr: PtolemaioV NeoV DionusoV Filopatwr FiladelfoV. The numbering as Ptolemy XII follows the convention of RE and is today standard. He is sometimes numbered as "Ptolemy XI" or "Ptolemy XIII" in older works. The name "Neos Dionysus" (the New or Young Dionysus) is attached to him by Porphyry, in Eusebius, Chronicorum I (ed. Schoene) 167. The earliest contemporary attestation is year 18 = 64/3 (pOxy 2.236(b)). It is possibly attested in a datable context on stele BM 886, the funerary stele of Psherenptah III, High Priest of Memphis, which gives the name in connection with the coronation of 76. G. Hölbl, The History of the Ptolemaic Empire 223, 282f., suggests that he may have assumed the title at this time, but the stele was erected in year 11 of Cleopatra VII = 42/41, so it is not direct evidence of contemporary usage. E. Bloedow, Beiträge zur Geschichte des Ptolemaios XII 83, notes that the title is never used when the king is named together with Cleopatra V, which suggests to me that the title may be connected with the reason she was removed as coregent. Ý

[2] Prol. Trogus 39. The name NoqoV means "Bastard" and is one of several indications in the later historians that his legitimacy was questionable. Pausanias 1.9.3 calls Berenice III the only legitimate child of Ptolemy IX, implying that Ptolemy XII in particular was not legitimate.

The effort by Cleopatra Selene to claim the throne of Egypt for her sons by Antiochus X in the mid 70s (Cicero, In C. Verrem 2.4.61), when Ptolemy XII was already king, was saying in essence that the claims of her sons were stronger than his. This is perhaps the strongest contemporary indication that there was some question about the status of his birth. However, its exact nature is unclear. The most relevant direct evidence is as follows:

i) In De Lege Agraria 2.42 Cicero describes Ptolemy XII as being royal in neither birth nor spirit ("neque genere neque animo regio esse").

Cicero notes that this was the opinion of "nearly all men" ("inter omnis fere"), i.e. there were some who disagreed. Further, in Pro Sestio 57 (delivered in 56) he extols the king's long and honorable ancestry. Clearly, he slanted his rhetoric to the needs of the occasion. In ordinary Latin usage "neque genere" would mean Ptolemy XII was not a Lagid by blood, but he certainly did not mean that the king was actually an imposter. But what the slur actually consists of is not spelled out.

From this evidence one can conclude that the illegitimacy, although widely accepted, was also disputed.

ii) E. Bloedow, Beiträge zur Geschichte des Ptolemaios XII 5ff., supposes (with most scholars) that De rege Alexandrino F9 is referring to Ptolemy XII when he refers to a king of Egypt as "a boy (puer) in Syria" at the time of his predecessor's violent death. Bloedow analyses Cicero's use of the term puer and concludes that Cicero meant that he was less than 18 at the time of his accession. Hence he concludes that Ptolemy XII must have been born in c. 98, while his father was king in Cyprus, at which time his mother can only have been a concubine.

This generally-accepted and apparently straightforward explanation suffers from two problems. First, it is difficult to explain how Ptolemy XII could ever have become engaged to a daughter of Mithridates, king of Pontus, as is discussed in more detail below. Second, it is unclear how there could be any dispute about his illegitimacy if this were correct.

iii) M. Chauveau, In Memoriam Quaegebeur 1263, 1265 n. 11 notes that in his titulary Ptolemy XII claims to be heir to the god Soter (i.e. Ptolemy IX) but, unlike all other kings, does not mention being heir to his mother.

This certainly means that his mother was not a ruling queen, but it does not prove she was a concubine, or anything else about her status.

W. Otto & H. Bengtson, Zur Geschichte des Niederganges des Ptolemäerreiches 177 n. 1 questioned the value of the classical evidence in toto. In addition to pointing to Cicero's statement in Pro Sestio 57, and noting the vagueness of De Rege Alexandrino F9, they also noted that Prol. Trogus 40 reintroduces the sons of Ptolemy IX with no suggestion of illegitimacy, and that Porphyry, in Eusebius, Chronicorum I (ed. Schoene) 167, introduces Ptolemy XII as the son of Ptolemy IX and brother of Berenice III with no suggestion of illegitimacy. They suggested that doubts arose about his legitimacy in the first place because of publicity about Berenice III, and particularly because she succeeded to the throne and he did not; it being forgotten that he was a hostage in Mithridates' court. These doubts were then exploited by the many powerful Romans who stood to gain advantage from the will of Ptolemy Alexander (assumed by Otto and Bengtson to be Ptolemy XI Alexander II rather than Ptolemy X Alexander I), which was said to have bequeathed Egypt to Rome.

However, they did not consider the action of Cleopatra Selene reported by Cicero, In C. Verrem 2.4.61, which is important evidence because it comes from a principal party who was not Roman. This makes it very difficult to accept their view that the charge was essentially baseless. Rather, it seems likely that there were in fact good grounds to doubt his legitimacy. However, the issue did not prevent him from being accepted as king in Egypt, and Cicero's clear, if slanted, statement in Pro Sestio 57 shows that the stain, although generally believed in Rome, was not universally held. This suggests that these grounds, while based in solid fact, were open to partisan interpretation.

More recent discussions have focussed on the meaning of "legitimacy" in Hellenistic culture. One possible view is that his illegitimacy is due to miscegenation. J. R. Barns, Or 57 (1977) 24 and R. D. Sullivan, Near Eastern Royalty and Rome 100-30 B.C. 92f., have suggested that Ptolemy XII was born to an aristocratic Egyptian, possibly from the family of the High Priests of Memphis, explaining his illegitimacy on these grounds. While I think the meaning of "legitimacy" holds the key to the issue, I do not think this particular solution is viable.

In my view, a more promising approach is that taken by D. Ogden, Polygamy, Prostitutes and Death, who notes that accusations of bastardy are very common in dynastic disputes of the Hellenistic period, and that the most common circumstance involves a dispute over the succession between sons of different mothers; he christens these "amphimetric" disputes. Ogden argues that the Ptolemies attempted to resolve this problem through the institution of incestuous marriage, but in time, as different Ptolemaic princesses married multiple kings, the problem essentially became resurrected through disputes between the families of different sisters.

There is one known son of Ptolemy IX whose birth occurred in circumstances which seem well suited to a dispute of this nature about legitimacy. This is the son who acted as eponymous priest in 109/8. While officially a son of Cleopatra Selene, the age data for other such princes suggests that he was in fact the son of Cleopatra IV, born to Ptolemy IX before his accession. This situation is unique amongst Ptolemaic heirs. The decision by Cleopatra III to force a divorce between Ptolemy IX and Cleopatra IV (Justin 39.3) provides a good reason to doubt the validity of the marriage of his parents. It is argued here that Cleopatra Selene later married Ptolemy X, and became the mother of Ptolemy XI. In these circumstances, there was a strong incentive for the partisans of Ptolemy X, including Cleopatra Selene to impugn the legitimacy of any sons of Ptolemy IX by Cleopatra IV.

This proposal was first made, so far as I know, by J. P. Mahaffy, A History of Egypt: The Ptolemaic Dynasty 225 n. 1, who presented the marriage between Ptolemy IX and Cleopatra IV as "morganatic". It has been generally ignored since then. The above analysis was made without knowledge of Mahaffy's proposal, I only discovered it later.

[3] Strabo 17.1.11. The term means "Piper" and refers to his fondness for playing the flute, an attribute which was regarded as highly reprehensible in a king. It is widely used to designate him today.

It is sometimes suggested that he is the Ptolemy "o Kokkes" and "Pareisaktos" of Strabo 17.1.8. On this point, see discussion under Ptolemy X. Ý

[4] Prol. Trogus 40, Porphyry, in Eusebius, Chronicorum I (ed. Schoene) 167. Ý

[5] There is no mention of his mother in classical or Egyptian sources. Various proposals exist in the literature:

i) His mother was a concubine. This is the standard theory (e.g. E. R Bevan, The House of Ptolemy 344) and is inferred from his illegitimacy. Speculation waxes lyrical from this point, with Bevan suggesting that she was "an accomplished and beautiful woman from some city in the Greek world" or "a dancing girl of plebeian origin", while M. Grant, Cleopatra 5, supposes with equal justice that she was "quite likely to have been a Syrian".

However, there is no necessary reason to draw this inference, and other explanations are possible, as discussed above.

In a refinement of this proposal, E. Bloedow, Beiträge zur Geschichte des Ptolemaios XII 5ff. argued that Ptolemy XII must have been 18 or less when he came to the throne, from which it would follow that he was born in the early 90s, at which time his mother could only have been a concubine.

If this analysis of his age is correct, then it is hard to draw any other conclusion. However there are difficulties with it which are discussed here.

ii) His mother was a concubine in the sense that she was not a Ptolemaic princess. This is argued by D. Ogden, Polygamy, Prostitutes and Death 92, 96f., who supposes that legitimacy was derived from being "sister-born" after the reign of Ptolemy VI.

In order to sustain this theory he must distinguish Ptolemy XII and his brother Ptolemy of Cyprus from the two children ("duos filios") of Ptolemy IX, said by Justin 39.4 to have been by Cleopatra Selene, that he left in Alexandria when he fled in 107, and explain what happened to the latter two, and there are no good grounds for doing so (see discussion under (iv) below).

His argument that being "sister-born" was a prerequisite of legitimacy is, I think correct, but it is not the whole story, for in order for a Ptolemaic princess to be a recognised sister she must also have been queen. At the time of the birth of her son(s) by Ptolemy IX, Cleopatra IV was not queen.

iii) His mother was of a social status considered questionable by some of the Greeks but acceptable as royalty in Egypt; on this basis she may have been an aristocratic Egyptian, possibly from the family of the High Priests of Memphis (J. R. Barns, Or 57 (1977) 24, R. D. Sullivan, Near Eastern Royalty and Rome 100-30 B.C. 92f., W. Huss, Aegyptus 70 (1990) 191, 203). This theory is by analogy to the marriage of Psherenptah II, High Priest of Memphis, to Berenice, proposed as a daughter of Ptolemy VIII.

This theory is essentially speculative, there is no direct evidence for it or against it. Additionally, there is now no evidence that Berenice was a daughter of Ptolemy VIII.

iv) His mother was Cleopatra Selene (W. Otto & H. Bengtson, Zur Geschichte des Niederganges des Ptolemäerreiches 177 n. 1). This theory denies that he was illegitimate, except by later inference based on a misunderstanding of the causes of the succession and by partisan propaganda. It identifies Ptolemy XII and his brother Ptolemy of Cyprus with the "duos filios ex Selene" of Ptolemy IX that he left in Alexandria when he fled in 107 (Justin 39.4). At least one of these children must have been male, and Otto and Bengtson, along with most scholars, assume both were (the alternative is that the other was a daughter, i.e. Berenice III).

Since Ptolemy XII and Ptolemy of Cyprus were engaged to two daughters of Mithridates VI, most probably in c. 81/0, they were almost certainly hostages at his court at the time, and the simplest way to explain how they got there is to suppose that they were among the grandchildren of Cleopatra III sent to Cos for safe keeping in 103 and kidnapped from there by Mithridates in 88.

If they were not the two children of Selene, then any boys born to Selene must have died earlier, or have been removed from Cos in some way before 88; otherwise, having more legitimate status than Ptolemy XII and his brother, any sons of Ptolemy IX by Selene would certainly have been sent to Cos in order to prevent them from falling into their father's hands, and they would have been preferred as husbands for the daughters of Mithridates.

The existence of at least one son who was recognised as a son of Selene is verified by SEG IX.5 and pdem Brooklyn 37.1796. However, this theory fails because Selene herself effectively repudiated the legitimacy of Ptolemy XII and his brother when her son by Antiochus X sought the throne of Egypt (Cicero, In C. Verrem 2.4.61), a point not considered by Otto and Bengtson.

v) That she was Cleopatra IV.

Unless Ptolemy XII was in fact born in c. 98, I think Otto and Bengtson are correct in identifying him and his brother Ptolemy of Cyprus with the children of Ptolemy IX abandoned in 107. The most likely source of error lies in taking Justin 39.4 as being correct when he says that they were children of Selene, i.e. that they were her biological children. The estimated birth date of the son of Ptolemy IX identified as Selene's son in SEG IX.5 and pdem Brooklyn 37.1796 shows that he cannot have been a biological son of Selene, who married Ptolemy IX at least a year after his birth. However, as the wife of the king, she was the official mother of his son and heir in year 9 = 109/8, when that son was mentioned in SEG IX.5 and as eponymous priest. For this son to be a biological son of Selene he must have been at most 6 years old, which seems doubtful in itself, and in any case is two years younger than the age of other Ptolemaic heirs when they performed the same role. Hence it seems most likely that Selene's position at that time was the same as that of Arsinoe II, "mother" of Ptolemy III, Ptolemy VIII "father" of Cleopatra III and (possibly) Berenice III "mother" of Ptolemy XI. But, since she was not the biological mother of Ptolemy XII she was in a position to repudiate his legitimacy if it became politically advantageous, which is what she did.

If Selene was not the biological mother, then the biological mother of Ptolemy IX's son and heir must have been in a relationship with Ptolemy IX c. 118, and must have had sufficient standing that her son would be recognized as Ptolemy IX's heir. Cleopatra IV fits the bill on both accounts.

In a long footnote, W. Huss, Ägypten in hellenistischer Zeit 332-30 v. Chr. 672 n. 3 argued strenuously against this proposal as "kaum aufrechterhalten" -- hardly sustainable. This is the only significant response I have seen, though S. Ager, JHS 125 (2005) 1, notes my proposal as an alternative to the standard genealogy.I have answered individual points of Huss' critique at the most appropriate place in these pages, but in summary his arguments, and my responses, are:

I must refute the clear testimony of Cicero, Trogus and Pausanias concerning Ptolemy XII's illegitimacy.

Not true. I only suggest that the notion of illegitimacy may have been used in ancient times to cover more scenarios than a simple out-of-wedlock birth. Nor am I alone in doing so.

I am forced to infer an error in Justin

Not true (and if it were true I would hardly be the first). I only suggest that Justin (or possibly Trogus) did not distinguish between biological and adoptive maternity. The primacy of adoptive relationships is well documented in the Ptolemaic dynasty; see the list above. There is good circumstantial evidence that the documented son of Ptolemy IX and Cleopatra Selene was not her biological child.

I must infer an impausibly short birth interval between Ptolemy XII and Ptolemy of Cyprus

It's certainly tight but not impossible or unprecedented. The exact limits are unclear since we do not exactly know when Ptolemy IX was forced to divorce Cleopatra IV. There is also the possibility that they were twins.

There is no evidence that king's sons who became eponymous priests had to be 8 years old. Even if the son of Ptolemy IX was 8 years old when he was eponymous priest, it would not prove he was a son of Cleopatra IV.

To the contrary, the independent evidence for all the other documented king's sons who became eponymous priests, including two who have been found since I published my paper, is strongly consistent with exactly this age.

As to Huss' second point: if we agree (if only for the sake of argument) that the son of Ptolemy IX was 8 years old in 109, he could not possibly have been a biological son of his official mother Cleopatra Selene. While not absolutely conclusive proof that this son of Ptolemy IX was therefore a son of Cleopatra IV, both the age and status point most strongly in that direction.

In De rege alexandrino F9, Cicero uses the term interfectus and therefore cannot be speaking of the death of Ptolemy X in battle, but must be speaking of the murder of Ptolemy XI.

While Cicero normally uses the term interfectus to refer to murder and similar types of illegitimately violent death, he does also use it to refer to death in battle, or even to suicide.

Describing Ptolemy XII as a puer in De rege alexandrino F9 would not be a gross error; for example Plutarch calls Ptolemy IX a meirakion when he was well over 50.

It is unclear why Plutarch's statement is relevant. The evidence is quite strong that Cicero used the term accurately. Even if he did not in this case, it is unclear how this strengthens the case that the fragment must refer to Ptolemy XII.

Huss did not address my argument, based on the Mithridatic captivity, that the probable son of Cleopatra IV was quite likely the same as the future Ptolemy XII.

On the other hand, if Ptolemy XII was in fact born in c. 98, then there is no known woman of the dynasty who could have been his mother. The only known candidate is his nurse Tryphaina, in who honour he erected a statue in year 22 = 60/59.

[6] Birth date of c. 117 estimated from the eponymous priesthood of a son of Ptolemy IX in his year 9 = 109/8 (C. J. Bennett, Anc. Soc. 28 (1997) 39, 47). This priesthood, and the mention of him in SEG IX.5, a decree creating a festival in Cyrene partly in his honour, show that he was being introduced to public life as the heir of Ptolemy IX at this time. Ptolemy Memphites and Ptolemy IX, as heirs to Ptolemy VIII, and Ptolemy Eupator, as heir to Ptolemy VI, had all served as eponymous priests, and we have reason to believe that each of these princes was 8 years old at the time; Ptolemy, son of Ptolemy VI and heir of Ptolemy VIII may also have been 8 or 9 years old when he was eponymous priest. If correct, it follows that we also have reason to believe that Ptolemy son of Ptolemy IX was probably 8 years old in 109/8, i.e. that he was born in year 1 = year 54 of Ptolemy VIII = 117/6, and probably earlier in this year rather than later, since a slightly later papyrus from 109/8 (pLondon 3.881, dated 23 Mecheir year 9 = 10 March 108) shows Ptolemy IX acting again as eponymous priest. He may possibly have been born the previous year.

W. Huss, Ägypten in hellenistischer Zeit 332-30 v. Chr. 672 n. 3 asserts that these analogies cannot be used to establish the minimum age of the eponymous priest. He gives no reason for this, it is simple ex cathedra. However, supposing it to be the case for the sake of argument, we can establish a maximum age for a biological son of Ptolemy IX by Selene. The earliest possible date for the birth of Berenice III was summer 115, so unless this son was a twin he was born no sooner than mid 114, making him no more than 5 years years old in February 108. In normal usage, this would make him still a very young child. On the proposed age, he was entering the phase of childhood when he was beginning to develop intellectual capability and understanding.

On the implications of this birth date for his maternity, see above. On the reasons for identifying this prince with the later Ptolemy XII, see discussion of the Mithridatic captivity.

The alternate view of a birth date of c. 98 is argued in most detail by E. Bloedow, Beiträge zur Geschichte des Ptolemaios XII 5ff., on the basis of Cicero, De rege Alexandrino F9. This fragment is argued to show that Ptolemy XII was less than 18 when he became king.

Bloedow further comments that if Ptolemy XII had been older than Ptolemy XI then the Alexandrians would have summoned him, not Ptolemy XI, to be the partner of Berenice III. This argument is absurd: Ptolemy XI had Sulla's ear, and Sulla was the most powerful man in the Mediterranean world at that time.

Only a few fragments of De rege Alexandrino survive, almost all of which are preserved with commentary in a palimpsest MS, itself very incomplete, which was recovered at Bobbio in the early 19th century. The Bobbio fragments, and the commentary of the Bobbio Scholiast, are published in T. Stangl (ed.), Ciceronis Orationum Scholiastae 91-93; all surviving fragments of the speech are collected in J. W. Crawford, M. Tullius Cicero: The Fragmentary Speeches 49-56. Stangl's fragment numbering is better known, but Crawford's is used here because she assembles the fragments from all sources.

The speech was delivered in 65 against a proposed annexation of Egypt. Fragments F9 and F10 (Crawford -- F8 and F9 Stangl) come from a section of the speech dealing with the activities and character of the king(s) of Egypt. Both are stated by the scholiast to be defences against the charge an unnamed king could not have been responsible for the violent death of a predecessor. In F9 Cicero says that when "the king" was killed "he" was a boy (puer) in Syria. This is normally joined with F10, which clearly describes the death of Ptolemy XI at the hands of the Alexandrian mob, and on this basis it is usually inferred that "the boy" must be Ptolemy XII. In further support of this, E. Bloedow, Beiträge zur Geschichte des Ptolemaios XII 5ff., analyses Cicero's use of the term puer and concludes that Cicero meant that he was less than 18 at the time (cf e.g. Philippics 3.3). Hence he concludes that Ptolemy XII must have been born in or after c. 98 BC.

The problem with this apparently very plausible interpretation is that it becomes extremely difficult, if not impossible, to explain how Ptolemy XII could ever have become engaged to a daughter of Mithridates, king of Pontus. While the evidence for the date and the circumstances surrounding this event is weak, the most widely accepted (and in my view most likely) reconstruction is that the engagement occurred because Ptolemy XII was a hostage at the court of Mithridates at the time of his father's death. But it seems impossible to explain how he came to be there on Bloedow's chronology. While he would certainly have been alive at the time of Mithridates' raid on Cos in 88, when Mithridates captured Ptolemy XI, there is no obvious reason why Ptolemy IX should have sent them from Cyprus to Cos in the first place.

The standard resolution of this difficulty is to suppose that the term puer does not have chronological significance, that Cicero meant the term ironically or sarcastically, e.g. R. D. Sullivan, Near Eastern Royalty and Rome 100-30 B.C. 92. If this resolution is accepted then the speech ceases to be evidence of his age.

W. Huss, Ägypten in hellenistischer Zeit 332-30 v. Chr. 672 n. 3, cites as analogous Plutarch, Lucullus 2.5, which calls Ptolemy IX "youthful" at a time when he was well over 50. Even if this interpretation of Plutarch is correct, the example is hardly relevant since Plutarch was writing in Greek around 200 years after the events he described while Cicero is a contemporary witness speaking in Latin. A more serious objection is that Plutarch may actually be referring to another son of Ptolemy IX rather than the king himself, a genuine youth, though this possibility is rejected here.

However, Bloedow's analysis of Cicero's usage seems sound to me on this point. Moreover, the Bobbio Scholiast is clear that Cicero is citing the king's age as a factor in defending him against a charge of involvement in his predecessor's death. Hence I think we must take the term puer seriously, as indicating that the king of F9 was 18 or less when his predecessor was killed.

On the other hand, it is not so clear that he must be Ptolemy XII. G. F. Hill, History of Cyprus I 205 n. 1, noted that F9, by itself, was completely ambiguous. While F9 and F10 can be combined to make grammatical and historical sense, there was no necessity, either in the texts themselves or in the commentary of the Bobbio Scholiast, to do so. F8 (F7 Stangl) and F6 (F6 Stangl), which occur in the same section of the Bobbio MS, are not contiguous, and indeed Crawford inserts her F7, from Aquila Romanus, De Figuris, between the two. Indeed, if F9 and F10 were originally contiguous, one must wonder why the Scholiast chose to split them. I pointed out, in C. J. Bennett, Anc. Soc. 28 (1997) 39, 49f., that if they are separated then fragment F9 could just as easily refer to the death of Ptolemy X, at which time his son Ptolemy XI almost certainly was under 18.

W. Huss, Ägypten in hellenistischer Zeit 332-30 v. Chr. 672 n. 3, objected to my proposal of separating F9 and F10 on the grounds that Cicero uses the term interfectus to describe the king's death, a term which Huss argues was associated with murder and execution rather than death in battle, and therefore could not apply to the death of Ptolemy X. It is true that Cicero usually uses the term in this sense, but there are occasions when he does use it to refer to death in battle -- e.g. Phil. 2.55, 13.7, 14.12 -- and he can use it in the casual sense of "killed" -- e.g. his use of it to describe the death of Mithridates VI in Prov. 27. With such examples in mind, it seems to me that we know too little about De Rege Alexandrino to insist that interfectus must on this occasion refer to the murder of Ptolemy XI.

In order to sustain this view, it is necessary to make other assumptions about the speech. The defence of royal character in these fragments was not simply a historical exegesis. The theoretical justification for the annexation was an attempt to enforce the will of a king Alexander or Alexas, who had supposedly willed the kingdom to Rome. It is clear that the argument, and even the existence of the will, was based on hearsay, and the Senate had elected not to take up the inheritance earlier. One may suppose, for example, that Cicero was reviewing the consequences of that action, and arguing that the policy was reasonable and moral, at least in part because, based on the facts known at the time of their accession, support for the following king(s) had been morally justified -- in particular, that they had not been involved in the deaths of predecessors.

Clearly, a critical issue for such a reconstruction is the identity of the "king Alexas" whose supposed will was at issue. For arguments that it was Ptolemy X Alexander I rather than Ptolemy XI Alexander II see here. For arguments against a supposed "Alexander III" see here.

Other points to note on this issue:

The kings are described in F9 as "ille rex" and "hunc" -- "that king" and "this (one)" -- and in F10 as "regem illum" (that king -- in this case clearly Ptolemy XI). If F9 and F10 are joined then "ille rex" refers to him in each case, and the "hunc" of F9 to the current king (Ptolemy XII), but if they are separated then there could well be a shift in temporal frame so that "ille rex" is the outgoing king in both F9 and F10 (Ptolemy X and Ptolemy XI) and "hunc" (in F9) is the incoming one (Ptolemy XI).

In the commentary on both fragments, the Bobbio scholiast notes that they are defences against charges of involvement in the death of his predecessor. But if they refer to the death of the same king (i.e. Ptolemy XI) then it is unclear why the defences offered in F9, particularly that of being off the scene, should require the additional defence offered in F10, or why the scholiast split the two fragments.

In the commentary on both fragments, the Bobbio scholiast names the king being defended as "Ptolemy", which is also how Cicero names Ptolemy XII in other speeches. If the king being defended in F9 was Ptolemy XI we would expect him to be differentiated as "Ptolemy Alexander" or "Alexander" or even "Alexas". But, if Cicero's references in other places to "Alexander" or "Alexas" refer to Ptolemy X then we do not actually know how Cicero would have identified Ptolemy XI, though admittedly some such identification seems likely. More significantly, since Cicero identifies both kings only by pronoun in the quoted extracts, we have no basis for knowing whether the scholiast is here following Cicero's practice or his own.

The statement that the king was in Syria is also problematic, for both scenarios. It is argued here that is more easily explicable if the king is Ptolemy XI rather than Ptolemy XII, since it then need not be understood as a precise location.

An additional item is pOxy 19.2222, a fragment of a chronicle of the Ptolemaic kings, which the editors restored as saying he died aged 4[4], based on the belief of A. Bouché-Leclercq, Histoire des Lagides, 357, that he was born in the mid 90s. However, although this papyrus evidently contained useful data, it is highly fragmentary and other restorations are clearly in error, such as apparent statements that Ptolemy VIII died aged 36 or that Ptolemy XI was 11 (or 29); the interpretation of the datum is very uncertain.

M. Passehl (pers. comm.) suggests that many of the Graeco-Roman statue portraits of Ptolemy XII (ignoring idealised Egyptian portraits) are of a very young man, which is unlikely if he came to the throne at the age of 36 or 37, as suggested here. However, this is a tricky argument to sustain, because the proposition that the apparent age of a portrait statue establishes at least a minimum age for a king is highly doubtful. The only certainly identifiable portrait statue, Alexandria 22969 (P. E. Stanwick, Portraits of the Ptolemies, E3), known to be Ptolemy XII by association with an inscription dated year 26 = 55 BC, is of a powerful middle-aged man. Stanwick identifies Alexandria 11275 (his E1), undeniably a teenager or very young man apparently associated with Isis, as Ptolemy XII on the Dionysian and Isiac associations of its context, but the evidence for the title "Neos Dionysos" dates from 64/3 or later, by which time he was certainly well into his thirties. Similarly, Louvre A28 (Stanwick's E7) appears to be a young teenager and Birmingham B.6771 (Stanwick's E9) is a boy: on no hypothesis can these be age-correct portraits of Ptolemy XII. Whether the iconography is not meant to represent biology accurately or Stanwick's attributions are incorrect, these portraits are a very unreliable guide to the king's age.

Another line of inquiry which is currently inconclusive, but which may at some point result in more definitive evidence, is the inscription SB I 4980 = iGrDelta I 753,18 = iGrAlex 33, a dedication by Ptolemy XII to his nurse Tryphaina in year 22 = 60/59. On the high chronology proposed here, she must have been about 75 at that time. On the low, she must have been about 50-55. Neither age is inherently improbable.R. Scholl, Aegyptus 69 (1989) 11, showed, based on Cypriote inscriptions of similar form (e.g. OGIS 163) that the fourth line should be restored as identifying her as the wife of Ammonios, a man with the high-ranking title of king's relative. If Ammonius can be identified, then his age would indicate hers, and hence the age of the king. The known candidates are as follows:

OGIS 163, from Old Paphos, also names a certain Ammonius, father of Aristonike, wife of Aristokrates, a "king's relative" (suggenoV) and royal secretary (upomnhmatografoV), indicating that this Ammonius was of very high status. T. B. Mitford, ABSA 56 (1961) 1 at 35 (no 95) held that OGIS 163 dated from the reign of Ptolemy X in Cyprus.

- Another candidate (or possibly the same man) is given by another statue dedication from Old Paphos, for Nikias priest of Asklepios for all Cyprus by a "king's relative" Ammonios (T. B. Mitford, ABSA 56 (1961) 1 at 38 (no 102 = SEG XX 206), which Mitford held to date from the reign of Ptolemy X or Ptolemy IX in Cyprus.

- Scholl also noted Cicero, Ad. Fam. 1.1, which names a certain Hammonius as an agent of Ptolemy XII at the time of his Roman exile in 57, shortly after this statue was dedicated.

Possibly related material is:

T. B. Mitford, ABSA 56 (1961) 1 at 39 (no 106): The base of a statue of Ploutos son of Ammonios son of Ploutos, erected by his grandfather, dated by Mitford to c. 120-80 based on the style of the lettering.

- An arciswmatofulakwn Ammonios is named in SB 14.11626 as strategos (epistates) of the Lycopolite nome in Thoth year 46 = October 125.

- A "(first) friend" ([prwtwn] filwn) Ammonios is named as strategos (epistates) of the Thinite nome in PSI 3.166-3.171 in Mesore year 52/Thoth year 53 of Ptolemy VIII = August-October 118. T. B. Mitford, ABSA 56 (1961) 1 at 38 (no 102), suggested that this was the same man as the second Ammonios above.

The Cypriote Ammonios/oi is/are possibly related to an earlier Ammonios, son of the Samian [---]os, arciswmatofulakwn of the city of Amathous, and of his wife Phila, daughter of the "friend" Karpion, who was son of yet another Ammonios. Ammonios was brother of Karpion and Pankrates. L. Mooren, Aulic Titulature in Ptolemaic Egypt, 199 (0363) and 210 (0394-0396) dates the inscription for this family to the last decade of Ptolemy VI. Another Ammonios, "friend", named in iSal 13.67, is dated to the first decade of the reign.

If the Hammonius of Cicero is the Ammonios of iGrDelta I 753,18 then it is surely more likely that he was in his 50s/60s in 57 than his 70s/80s. On the other hand, if SEG XX 206 has been correctly dated, it seems unlikely that the two Ammonioi are the same man, unless this inscription was late in the Cypriote reign of Ptolemy IX and Ammonios was a young man at the time -- which conflicts with Mitford's proposed identification with the Thinite strategos. Since there are at least two Ammonioi with the title "kings' relative" who could have been alive in 60/59, we currently have no grounds for deciding which was the husband of Tryphaina and hence no basis for estimating her age, nor the king's on the basis of her age. Ý

[7] If he was born in 117, his father was governor of Cyprus at the time, and since his probable mother Cleopatra IV was later able to commandeer a large part of the Ptolemaic fleet there (Justin 39.3) it is likely that she too was in Cyprus at the time. If he was born in c. 98, his father was king in Cyprus at the time. Hence, on both of the scenarios discussed here, he was born in Cyprus. Ý

[8] pdem Brooklyn 37.1796 = pdem Recueil 6, dated 30 Tybi year 9 = 15 February 108. On the implications of this papyrus for his birthdate and maternity, see discussions above and C. J. Bennett, Anc. Soc. 28 (1997) 39, 47. Ý

[9] Justin 39.4, who refers to two children ("duos filios") of Cleopatra Selene, at least one of which was male. Whether or not the (eldest) son is to be identified with Ptolemy XII, he was most likely to be identified with the eponymous priest of the previous year. If so, Selene must have been his adoptive mother.

Two Cypriot inscriptions, iKition 2003 and RDAC 1968 74.4, refer to children (teknwn autou) of king Ptolemy Soter. In view of the king's title and the fact that there is no connection to Cleopatra III, these must date from the period of Ptolemy IX's sole rule in Cyprus, and so prove that he had living children at that time, whether or not they were themselves present in Cyprus. Neither inscription is precisely datable. However, iKition 2003 begins with an invocation to Zeus Soter and Athena Nikephoros. T. B. Mitford, AfP 13, 14 at 34, pointed out that this implies that the inscription must have been dedicated on occasion of a victory. The two obvious occasions are his reconquest of Cyprus in 105 and his victory over the Maccabean king Alexander Ianneus in 103. Although Mitford thought the later date seemed "in itself more likely", the earlier occasion seems more likely to me, since, as Mitford notes, the inscription also refers to troops acting as bodyguards in Kition and to holders of high court rank as officers in the army. But in any case it proves that there were living children in 105. These are almost certainly the "duos filios" of Justin. Ý

[10] Inferred from Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 13.13.1, which describes how Cleopatra III sent her grandchildren to Cos at the start of her war against the threatened invasion of Egypt by Ptolemy IX. These would certainly have included all the sons of Ptolemy IX. It is rather less likely to have included his daughter (Berenice III), since she is attested as queen within 10 days of the last known mention of Cleopatra III, implying that she was already in Alexandria at the time of her grandmother's death. Ý

[11] Inferred from Appian, Mith. 4.23, which describes the capture of Cos, with an Egyptian prince (Ptolemy XI), by Mithridates VI in 88, and Appian, Mith. 16.111, which mentions, in connection with his death in 63, that two of his daughters had been engaged to the kings of Egypt and Cyprus, i.e. to Ptolemy XII and Ptolemy of Cyprus. The engagement almost certainly took place in c. 81/0, before Ptolemy XII became king, which immediately raises the question of how this could have happened.

E. Bevan, The House of Ptolemy 345, and G. H. Macurdy, Hellenistic Queens 176, note that Appian described the two princesses as Duo d' autwi qugathres eti korai suntrefomenai -- "two of his daughters, still maidens, were brought up together ....". The translation cited here is reflexive ("were brought up together [with each other]"), and some argue (e.g. Mark Passehl, pers. comm.) that this is the obvious and intended sense. However, Bevan and Macurdy argued that the verb suntrefomenai should require reference to a third party, and that grammatically the reference was to autwi -- i.e. "two of his daughters were brought up together with [him, i.e. Mithridates]" -- but noted that this makes little sense. Bevan and Macurdy argued that the intended sense was that they were brought up with the kings of Egypt and Cyprus to whom they had been engaged. This interpretation has been generally accepted by Ptolemaicists, although it is recognised (e.g. R. D. Sullivan, Near Eastern Royalty and Rome 100-30 B.C. 369 n. 12) that the scope of suntrefomenai is "ambiguous in context".

If the princes were engaged to girls who had grown up with them, it would follow that they were among Mithridates' hostages, and the only known way they could have become so is through capture in the raid on Cos in 88. The major remaining objection to identifying them with the "children of Selene", who were almost certainly sent to Cos in 103, is the imputation of illegitimacy, which is explicable if the two were biologically sons of Cleopatra IV.

Technical issues of ambiguity in Greek syntax (or lack thereof) aside, there are some difficulties with this reconstruction.

1) Appian, Mith. 4.23 only identifies one Egyptian prince as being captured in the raid on Cos, a son of Ptolemy X (the later Ptolemy XI).

However, this does not of itself prove that only one prince was captured. Appian makes a point of mentioning that the prince was the son of the then-ruling king of Egypt, underscoring the enormity of what Mithridates had done, and that may have been the reason to mention him, rather than inventorising the spoils.

2) Appian, Mith. 8.55, reports that the terms of the Peace of Dardanos, concluded in 85, included the return of prisoners; presumably these would have included any Ptolemaic princes captured at Cos.

However, it is far from clear that this included hostages such as the sons of Egyptian kings, especally when Egypt was not allied to Rome. As reported by Appian, it consisted of captured Roman generals and prisoners, as well as deserters and runaway slaves, and also deported populations, notably the Chians. It is uncertain when Ptolemy XI escaped from Mithridates (Appian, Civil Wars 1.102), but it is generally held to be around or shortly after the Peace of Dardanos. If he was not surrendered at that time, neither would other Ptolemaic princes have been. In any case, a surrender at this time presumes that they were turned over to Roman custody, which almost certainly did not happen.

3) As noted above, fragment F9 (F8 Stangl) of the lost speech of Cicero, De rege Alexandrino, has usually been interpreted as showing that Ptolemy XII was less than 18 (a "puer") when Ptolemy XI was murdered in mid 80. This would imply that he was born in the early 90s, at which time his father Ptolemy IX was king in Cyprus. There is no obvious reason why he should then have sent his sons to Cos.

This difficulty is usually avoided by supposing that Cicero's use of the term "puer" was not intended literally; my preference, argued above, is that the fragment refers to Ptolemy XI rather than Ptolemy XII.

4) The same fragment says that he was "in Syria" at the time of the previous king's death. E. R. Bevan, The House of Ptolemy 345, having failed to find any MS support for emending "Syria" to "Cyprus", proposed to explain the reference by assuming that Ptolemy XII traveled from Pontus to Egypt via Syria. But the passage appears to be referring to a place of residence rather than a point of transit. Also, whereabouts in Syria was he? R. D. Sullivan, Near Eastern Royalty and Rome 100-30 B.C. 92, followed by J. Whitehorne, Cleopatras 178, suggested that Mithridates had transferred custody to Tigranes of Armenia, who, he held, then controlled much of northern Syria, for some reason, but it seems to me most unlikely that Mithridates would releases hostages of such potential value out of his direct control. One might expect a coastal region, but these were under the influence of his aunt (and step-mother?) Cleopatra Selene, who certainly did not accept the validity of his claims. The other possible areas -- Judea or Emesa -- seem even less likely.

Sullivan's analysis is based on Appian, Syriaca 8.48 who specifies that Tigranes ruled Syria for 14 years. Justin 40.1 gives Tigranes 18 years. The extra 4 years is the period between his withdrawal from Syria, forced by Lucullus in 69, and the final defeat of Mithridates. On this widely-accepted chronology, Tigranes' conquest of Syria was in c. 83. However, this date is disputed. O. D. Hoover, Historia 56 (2007) 280 at 296-298, argues for a date of c. 75. Hoover advances this proposal on several grounds:

Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 13.16.4, dates the invasion to the reign of the Maccabean queen Alexandra Salome, 76/5-67/6. Also, at the time of the invasion Josephus describes Cleopatra Selene as ruling over Syria.

- Tigranes would not have moved into Syria before moving into Cappadocia and Cilicia, which Appian, Mith. 10.67, indicates was suggested by Mithridates after learning of Sulla's death in 78.

- Cicero, In C. Verrem 2.4.61, states that, at the time Selene's sons visited Rome in c. 75 to claim the throne of Egypt, they ruled Syria "without dispute, as they had received it from their father and their ancestors", which would not be the case if Tigranes rules Syria at the time.

- The total number of obverse dies used by Tigranes' Antiochene mint (56-67) suggests a usage rate of 4-5 dies per annum if he took control in 83, which is significantly lower than the norm for the late Seleucids. Dating his rule from c. 75 doubles this rate, bringing it closer to normal rates.

These arguments seem reasonable to me, though not all are equally strong; for example, since Josephus ends his account of Tigranes' Syrian invasion invasion with the fall of Ptolemais in 69, he has undoubtedly compressed the events of several years. Notwithstanding such cavils, if this redating is essentially correct it opens up other possibilities for Auletes' residence before returning to Egypt since the history of Syria at this time is largely blank if it was not ruled by Tigranes, e.g. that he and his brother were in Antioch as guests of Philip I, or in Damascus. It still remains hard to explain why they would have needed to engage themselves to Mithridates' daughters on such a scenario.

The problem of locating a residence for the "puer" also exists if the fragment is assigned to Ptolemy XI in 88/7 rather than Ptolemy XII in 81/0, since Mithridates did not directly control any part of Syria at either time. However, we have another option here: that the term is simply vague. This date is very shortly after the kidnapping, at which time Mithridates was fully engaged in warfare in Greece and Asia Minor. Appian Mith. 4.23 indicates that Mithridates treated him well, but the text does not require that he was by Mithridates' side the whole time. Knowledge of his movements during his captivity must ultimately derive from Ptolemy XI himself, and it is perfectly possible that he did not always know where he was.

These problems do not arise if we assume that the princes were not Mithridates' hostages in 80. Appian's statement is the only positive evidence that they were in fact hostages, and, as we have seen, there are linguistic difficulties with that interpretation. But, quite apart from the syntactical debate, there are some serious circumstantial problems if we assume that they were not hostages:

1) If the princes were not hostages, why would they agree to such an engagement, so contrary to Ptolemaic practice?

The advantages to Mithridates are clear: had the marriages occurred, they would have reinforced his influence over them, just as the marriages of his daughters to the kings of Armenia and Cappadocia (in c. 95 and 81) had done. Unless the engagements were a conditon of leaving Mithridates' court, the advantages to the two princes are not nearly so clear. Mithridates held no position or (known) influence in Egypt, and there is no indication, for example, that the princes received Pontic money or troops, nor is there any clear reason why they should have asked for them.

2) What happened to the other princes sent to Cos in 103 (presumably, the "children of Selene")? On this scenario they were almost certainly not mentioned by Appian in connection with the raid on Cos because they were not there.

One could speculate that any male children had died, or that Ptolemy IX retrieved them from Cos once he was settled in Cyprus. In support of this, Josephus, Ant. Jud. 13.13.4, describes how Ptolemy IX summoned Demetrius III to be king in Damascus from the nearby island of Cnidos, which certainly implies that he had the ability to recover his sons from Cos at this time if he wished to do so. Though, if Ptolemy IX retrieved his sons, from a defunct marriage, one has to wonder why Ptolemy X, then securely king of Egypt, did not also retrieve his son, from an equally defunct marriage.

Nevertheless, there is one possible datum to support the latter scenario: the "youthful" Ptolemy of Plutarch, Lucullus 2.5, if he is in fact a son of Ptolemy IX. He would then be in his early 20s in 86, making him probably a "son of Selene" in this scenario. However, he is usually understood to be the king himself. See discussion here.

3) If the princes were not hostages, and we still assign F9 (F8 Stangl) of De rege Alexandrino to Ptolemy XII, we still unable to explain what he was doing in Syria when Ptolemy XI died.

If anything we are worse off, since the proposals made on the assumption that they were hostages would no longer be possible. As noted by E. Bevan, The House of Ptolemy 344 n. 3, we would otherwise expect Cyprus, the other Ptolemaic domain. (However it would still be possible to assign this fragment to Ptolemy XI.)

It is certainly possible to concoct scenarios that address these issues. However, it is, in my view, necessary to resort to an unacceptable degree of speculation to do so. Once a possible explanation for "bastardy" is found for a "son of Selene", the only real indication that solutions like these might be required is the doubtful reference to a son of Ptolemy IX in Plutarch, Lucullus 2.5. By contrast, the issues raised by explaining the engagement through the hostage scenario can all be addressed by making careful interpretations of the appropriate texts. In essence, my view is that fewer and more reasonable assumptions are required if we suppose that the engagement occurred because the "children of Selene" were captured by Mithridates VI in 88, to become the later kings Ptolemy XII and Ptolemy of Cyprus.

On the exact date of this event, see discussion under Ptolemy XI. Ý

[12] See discussions under Ptolemy IX and Ptolemy XI. Ý

[13] First attested on oPr. Joachim 1, dated 8 Tybi Year 2 = 17 January 79. Ý

[14] First attested on oPr. Joachim 1. The identity of the sibling referred to in this title has been debated, though it is generally agreed that the "father" is Ptolemy IX, since it is generally supposed that Cleopatra V was a daughter of Ptolemy IX. G. H. Macurdy, Hellenistic Queens 176, identified the AdelfoV as the other partner in the royal couple, and P. W. Pestman, Chronologie égyptienne d'après les textes démotiques (332 av. J.-C. - 453 ap. J.-C.) 78(e), adopting this suggestion, further argued that the fact the Ptolemy XII kept the title after 69 proved that Cleopatra V had not fallen in disgrace. E. Bloedow, Beiträge zur Geschichte des Ptolemaios XII 85 proposed that the title referred to Berenice III. L. Criscuolo, Aegyptus 70 (1990) 89, argued that Ptolemy IX had given the title to all his children in order to promote harmony amongst them, but there is no evidence that Ptolemy of Cyprus ever bore the title. In view of the genealogy suggested here for Cleopatra V, I would propose a different explanation: that Ptolemy XII and Cleopatra V were honoring each of their fathers, Ptolemy IX and Ptolemy X, and were also honoring not only each other but each of their siblings who had been murdered in the year of their accession, Berenice III and Ptolemy XI. In other words, I suggest that the titles are an expression of a desire for reconciliation and reuniting of the feuding branches of the Ptolemaic dynasty. Ý

[15] Stele BM 886, the funerary stele of Psherenptah III, High Priest of Memphis, states that he was born in year 25 of Ptolemy X = 90/89 and was made High Priest when he was 14, when he crowned Ptolemy XII. Ý

[16] Terminus post quem: OGIS 185 = iGPhilae 50, recording a dedication for the royal family at Philae; terminus ante quem: pdem Ashm. 16/17. The significance of her disappearance from the record has been much debated, see C. J. Bennett, Anc. Soc. 28 (1997) 39, 57ff. Normally, it would be assumed that she had died; so F. Stähelin, RE 11 748. However, reliefs on the pylons of the Temple of Edfu show Ptolemy XII and Cleopatra V, and the lintel of the doorway between them has an inscription commemorating the fitting of the doors dated to 1 Choiak of year 25. J. Dümichen, ZÄS 8 (1870) 1, assigned this inscription to Ptolemy XII, and concluded that it proved Cleopatra V was still alive on 5 December 57. This, combined with the evidence that Berenice IV ruled with a coregent also called Cleopatra Tryphaena, led many (e.g. A. Bouché-Leclercq, Histoire des Lagides II 145 n. 1) to argue that she had not died but had been removed from power. P. W. Pestman, Chronologie égyptienne d'après les textes démotiques (332 av. J.-C. - 453 ap. J.-C.) 78(e) argued in support of this that the fact that Ptolemy XII continued to use the title FiladelfoV after her disappearance showed that she cannot have fallen in disgrace, though other interpretations of this title are certainly possible. Yet Dümichen's date falls in the period when Ptolemy XII had been expelled from Egypt by Berenice IV, and other evidence that Ptolemy XII was recognised as sole ruler in Upper Egypt during this period has all been reassigned to other dates. J. Quaegebeur, in L. Criscuolo & G. Geraci, Egitto e storia antica dall'ellenismo all'età araba 595, examined the inscription on the lintel in light of the building history of the site, and proposed instead that it should be dated to year 25 of Ptolemy X, i.e. 13 December 89. Nevertheless, he argued that the iconographic evidence of the pylons supports the theory of a fall from power, since it includes empty cartouches that were clearly intended for Cleopatra V, and clear evidence that images of Cleopatra V were plastered over in antiquity, in that they did not suffer from the vandalism that damaged other parts of the reliefs in Christian times. Quaegebeur proposes that the decoration of the pylons continued after Ptolemy XII and Cleopatra V dedicated the building in 70, and that the reliefs were not quite complete when she was removed from office in late 69. Ý

[16.1] Inscription first published in W. Vollgraff, BCH 25 (1901) 359 at 365ff. The inscription includes a list of victors at the Basileia of an unspecified date, including "King Ptolemy Philopator". Vollgraff naturally dated the inscription to Ptolemy IV. However, M. Holleaux, BCH 30 (1906) 469, reexamined it and noted a number of epigraphical and prosopographical features that strongly favoured a later date. Most notably, the victor for the pair of foals at the same Games was a Roman, which would be most unexpected at such an early date, and hardly conceivable during the Second Punic War, then still being fought. Holleaux proposed two alternate candidates: Ptolemy Neos Philopator, then thought to have been a coregent at the end of the reign of Ptolemy VIII, and Ptolemy XII Philopator and Philadelphus.

Subsequent research has shown that Neos Philopator was almost certainly the posthumous epiklesis of a son of Cleopatra II chosen at the time of his inclusion in the dynastic cult, most likely Ptolemy Memphites, which excudes him as a candidate. Four other kings after Ptolemy IV are known to have been called "Philopator": Ptolemy XII, Ptolemy XIII, Ptolemy XIV and Ptolemy XV. The last two can be ruled out, since they were junior coregents to Cleopatra VII and unlikely to have independently sponsored chariot events, and the brief reign of Ptolemy XIII was too unsettled for it to be likely that he had the ability to do so. That leaves Ptolemy XII as the most likely candidate.

As to the date, it must be the earlier part of his reign, before he adopted the title Neos Dionysos, which is first documented in year 18 = 64/3. Beyond that it is difficult to place any limits at this time. Ý

[16.2] Suetonius, Caesar 11, notes that in the year of his aedileship, A.U.C. 689 = 65, "Caesar made an attempt through some of the tribunes to have the charge of Egypt given him by a decree of the commons, seizing the opportunity to ask for so irregular an appointment because the citizens of Alexandria had deposed their king, who had been named by the senate an ally and friend of the Roman people." This is evidently connected to the debate which Cicero, De lege agraria 2.44, refers to as concerning the acquisition of Egypt in that year, which, according to Plutarch, Crassus 3.1, was initiated by the censor M. Licinius Crassus.

Interpreting Suetonius' statement to refer to a contemporary event, some early 19th century Ptolemaicists inferred that Ptolemy XII had been temporarily deposed in this year, supposedly by a "Ptolemy Alexander III" (the Alexas of Cicero, De lege agraria 2.41), who was himself deposed in turn, dying in Tyre, and willing Egypt to Rome. There is no trace of such a sequence of events in the Egyptian record, though any such reign would admittedly have been brief. Moreover, Cicero's speech makes it clear that the event had occurred earlier. The speech was against a new agrarian law proposed by the tribune P. Servilius Rullus to replace an earlier law, passed (De lege agraria 2.56) in the consulate of L. Cornelius Sulla and Q. Pompeius Rufus, i.e. A.U.C. 656 = 88. Cicero notes (De lege agraria 1.1) that the bequest became effective after this, yet in De lege agraria 2.41 & 2.42 he implies that the very existence of the will is a matter of controversy and for the existence of a senate resolution accepting the bequest he cites the authority of L. Phillipus, cos. A.U.C. 653 = 91. Evidently, as noted by E. Badian, RhMp 110 (1967) 178 at 190ff., the events had transpired many years earlier, for such doubt would not have existed at the beginning of 63 about events that only occurred at most two years earlier.

As to the identity of the king in question, the circumstances described by Suetonius fit Ptolemy X, who, while only hypothetically a "friend and ally" of Rome, was deposed exactly as described, rather than Ptolemy XI, who, while certainly a "friend and ally" of Rome, was murdered. Ptolemy XII was not recognised as a Roman "friend and ally" until early A.U.C. 695 = 59, with the help of some extremely large bribes (Dio 39.12; Suetonius, Caesar 54; Cicero, Ad. Att. 2.16.2).

J. W. Crawford, M. Tullius Cicero: The Fragmentary Speeches 47, suggests that Suetonius was actually referring to the debates in 56 concerning the restoration of Ptolemy XII, and that he had misdated the reference. Ptolemy XII's circumstances at this time certainly match the description of the point at issue perfectly. However, even though Caesar remained engaged with Roman politics, at this time he was fully preoccupied with the conquest of Gaul and was in no position to consider an Egyptian adventure. Since Suetonius' statement makes perfect sense in the context he gives it, there seems no reason to redate it. Ý

[16.3] Appian, Mith. 17.114, notes that Ptolemy XII asked for Pompey's help to "suppress a sedition" in this year. No help was given and no other details are known. Ý

[17] Porphyry, in Eusebius, Chronicorum I (ed. Schoene) 167 is the only classical source to mention both queens. Strabo 12.34, 17.1.11, and Dio Cassius 39.57.1, only know of Ptolemy XII being replaced by Berenice IV. However, the existence of the joint regime is certain because of BGU 8.1762, an undated papyrus that refers to "the queens".

Porphyry calls Cleopatra Tryphaena a daughter of Ptolemy XII, not his wife. For this reason she is numbered as Cleopatra VI Tryphaena by some historians. However, it seems more likely to me that she was in fact his wife; see discussion under Cleopatra V on the identity of Cleopatra VI Tryphaena.

J. E. G. Whitehorne, Akten des 21. Internationalen Papyrologenkongresses Berlin 1995 II 1009, has suggested that the two queens were not coregents but opponents. The primary evidence he cites is gr Medinet Habu 43 (H. J. Thissen, ZPE 27 (1977) 182), datable to this general period by mention of the Theban strategos Kalasiris son of Monkores, and dated to 1 Tybi year [2]6 of king Ptolemy = year [3 or 4] of queen Cleopatra = 4 January 55. Thissen argued that the reconstruction of year 26 is confirmed by the equation of 1 Tybi = day 12 of a lunar month, i.e. day 1 = 20 Choiak: according to the lunar cycle reconstructed by A. E. Samuel, Ptolemaic Chronology 59, this happens on the second year of the cycle, and year 26 also corresponds to the second year of the cycle. On the assumption that "queen Cleopatra" is Cleopatra V Tryphaena, L. M. Ricketts (BASP 27 (1990) 49, 58) had already argued that this graffito proved she was still alive in 55. Whitehorne extends this by noting that "Cleopatra" is not identifiable in the dating formulae of Berenice IV, and hence argues that the graffito is proof of a revival of the joint regime, and that Cleopatra V had represented the interests of Ptolemy XII in opposition to Berenice IV while he was in exile trying to raise Roman support.

Whitehorne's proposal seems extremely doubtful to me. Most of the data he cites, which either names no ruler or names only Berenice IV as queen, perhaps as coregent with Archelaus, is moot because, according to Porphyry, Cleopatra (V) Tryphaena died after the first year, and therefore her absence is expected. BGU 8.1762 refers to a strategos and a dioiketes who evidently reported to both, a point that Whitehorne mentions but then chooses to ignore, though it would seem to require a joint regime. Further, if he was correct then he must explain not only why Cleopatra is dated according to the years of Ptolemy's opponents, but also why she again drops out of the dating formulae after this graffito.

There is some evidence that Ptolemy XII continued to be recognised as king in Upper Egypt during his absence, though all evidence apparently naming him alone in year 25 has been reassigned either to year 25 of Ptolemy X or to other years of Ptolemy XII: OGIS 188, 189 reassigned to Ptolemy X on prosopographical grounds (P. R. Swarney, The Ptolemaic and Roman Idios Logos 22); the lintel of the doorway at the temple of Edfu reassigned to Ptolemy X after examining its place in the sequence of the history of the building (J. Quaegebeur, in L. Criscuolo & G. Geraci (eds.), Egitto e storia antica dall'ellenismo all'età araba 595); BGU 8.1772 and BGU 8.1871 reread from year 25 to year 21 and pBerol. 13657 reread from year 25 to year 29 (T. C. Skeat, The Reigns of the Ptolemies 38). It would seem to me that the last is perhaps questionable, because Skeat notes (p. 39) that it has the effect of making Heliodorus strategos twice, once in year 21 (BGU 8.1871) and again in year 29 (pBerol. 13657), with Paniskos in between, but it appears to have been generally accepted.

These amendments leave only double dates for Ptolemy XII being attested in this period. Aside from gr Medinet Habu 43, we have the following ones: pdem Louvre 3452 (year [2 or 3] and year 25) and odem Kaplony-Heckel 14 and 15 (year 2[3 or 4] = year 2 and year 24 = year [2 or 3]); the dates of these inscriptions are discussed below. These show that the Thebans covered their bets during the reign of Berenice IV and continued to recognise Ptolemy XII as king, even as primary ruler, throughout the period of his exile. Therefore, the proposal of L. M. Ricketts (BASP 27 (1990) 49, 59, that gr Medinet Habu 43 marks the restoration of his regime in Upper Egypt, is without foundation. Even though only gr Medinet Habu 43 names the other ruler, the fact that she is called Cleopatra does not prove she was not Berenice IV -- we only have one certain named attestation for her reign (pOxy 55.3777). Quaegebeur notes that by this time, "Cleopatra" was the standard name for a ruling queen. W. Huss, Aegyptus 70 (1990) 191, 194 n. 12, equates the "Cleopatra" of gr Medinet Habu 43 to Berenice IV without comment, presumably for this reason. Ý

[18] Not in the Canon of Ptolemy since the reign of Berenice IV is circumscribed by that of Ptolemy XII.

The earliest agreed date for Berenice IV is 9 Epeiph of year 1, BGU 8.1757. The ruler for this papyrus is unnamed, and it was originally dated by W. Schubart, the editor of BGU VIII, to Cleopatra VII. It names Paniskos as strategos of Heracleopolis. T. C. Skeat, Reigns of the Ptolemies 38, notes that Paniskos is named in year 26 Pharmouthi 19, Seleukos in year 30 Mecheir 14 and perhaps Payni 20, Paniskos in year 1 Epeiph 9, Seleukos in year 1 Epeiph 14, Paniskos in year 2 Choiak 27, and Seleukos in year 2 Tybi 11, i.e. we appear to have Seleukos and Paniskos alternating as strategos almost daily. However, if the two year 1 dates for Paniskos are assigned to Berenice IV rather than Cleopatra VII then the two strategoi can be placed consecutively, Paniskos down to some date between year 26 and year 30 and Seleukos thereafter. This reasoning has been generally accepted.

The latest date for Ptolemy XII is less clear. oThebes 14, a tax receipt dated 9 Epeiph year 23 (inexplicably redated to 10 Mesore by T. C. Skeat, Reigns of the Ptolemies 37, followed by A. E. Samuel, Ptolemaic Chronology 155; it does refer to a later payment on 30 Mesore of the same year, which is presumably the source of Skeat's comment) is assigned to Ptolemy XII by Skeat, making it the latest date before his expulsion, corresponding to 12 July 58, and dated to the same day as BGU 8.1757. However, oThebes 14 is one of seven ostraca in this collection referring to Pikos son of Permamis. The other six are dated to years 20, 21, 23, 30, 5 and 6. J. G. Milne in A. H. Gardner et al., Theban Ostraca 79 n. 1, pointed out that the series could belong either to Ptolemy X (years 20-23) followed by the second reign of Ptolemy IX (year 30) and Ptolemy XII (years 5 and 6), covering a total of 19 years (94-75), or to Ptolemy XII (years 20-30) followed by Cleopatra VII (years 5 and 6), covering a total of 15 years (61-46). Milne rejected the latter possibility since Cleopatra VII was associated with Ptolemy XIV in those years and so he thought that the later ostraca should then be double-dated; but in fact there are no dates for Ptolemy XIV. Presumably this is the reason Skeat felt able to override Milne's verdict, which is not stated.

To my mind, the difference between an interval of 19 years and one of 15 years is not so great as to allow us to favour one solution over the other; perhaps Skeat was also swayed by the fact that the first solution requires Pikos to survive the Theban rebellion of 89/8, which was put down by Ptolemy IX with great ferocity. Also, oThebes 30, which also names Pikos son of Permamis, is dated 1 Phamenoth year 30 = 4 March 51 if assigned to Ptolemy XII. This is only 18 days before Cleopatra VII is first attested as queen on iBucheum 13, presiding over the installation of the Buchis Bull, though it is certainly possible that the news had not yet reached Thebes, and besides that attestion comes from the reign of Augustus. If oThebes 14 should be dated to Ptolemy X rather than Ptolemy XII, then the latest date I have located which can be assigned to Ptolemy XII is BGU 8.1756, 13 Pachon year 23 = 17 May 58.

M. Depauw, in C. J. Bennett & M. Depauw, ZPE 160 (2007) 211, presents a new argument on this point which seems to conclusively assign this ostracon to Ptolemy XII. The officiating sittologos Hermias is also known from oThebes 12, oWilcken 720 and oBod 1.220, which last names him together with another sittologos, Kronios. He in turn is also named on several other ostraca, including oThebes 13, oWilcken 722 and oWilcken 1355. This last is dated to year 28, a year number which only occurred with Ptolemy XII in the first century. Hence Kronios, Hermias and Pikos are all dated to Ptolemy XII, and oThebes 14 gives his latest date before Berenice IV. As Depauw notes, the internal mention of 30 Mesore in the same year simply indicates that the scribe did not see fit to mention the change of ruler.

Based on the reading of the date of pdem Louvre 3452 as year 2 and year 25, it was until recently generally supposed that year 1 of Berenice IV was equivalent to year 24 of Ptolemy XII, i.e. 58/7. However, M. Chauveau, Akten des 21. Internationalen Papyrologenkongresses Berlin 1995 I 163, 166f., reviewed the source data for all the known double dates after U. Kaplony-Heckel, in S. Israelit-Groll (ed.) Studies in Egyptology Presented to Miriam Lichtheim 580, published odem Kaplony-Heckel 14 and 15 and read them as dating to year 23 = year 2 and year 24 = year 3, implying year 1 = year 22! As a result, Chauveau corrected the readings for both these ostraca to year 24 = year 2, for pdem Louvre 3452 to year 3 = year 25, and for gr Medinet Habu 43 to year 26 of king Ptolemy = year 4 of queen Cleopatra. Consequently, year 1 of Berenice IV is equivalent to year 23 of Ptolemy XII, i.e. 59/8, not year 24. Thus the date of BGU 8.1757, 9 Epeiph of year 1, translates to 12 July 58. This is the terminus ante quem. If oThebes 14 is correctly assigned to Ptolemy XII, as now seems certain, she must have acceded at most a few weeks earlier. This chronology fits well with pOxy 19.2222, which states that Ptolemy XII was in exile for two years, i.e. two full years, his years 24 and 25.

One document with a possibly earlier date for Berenice IV is BGU 8.1755, read by Schubart as 29 Thoth year 1?. A. E. Samuel, Ptolemaic Chronology 157 originally assigned it to Cleopatra VII, making the date correspond to 3 October 52. This is problematic, since it is considerably earlier than our other indications for the death of Ptolemy XII. He later noted (A. E. Samuel, CdE 40 (1965) 376, 392 n. 1) that it contains a reference to Paniskos and therefore, following Skeat's argument, should be assigned to Berenice IV, which would, in light of Chauveau's redating of Berenice IV, make the date correspond to 5 October 59. However, this is equally problematic, because it is even more considerably earlier than oThebes 14. As far as I can determine, this suggestion has subsequently been ignored (e.g. BGU 8.1755 is omitted from the lists of documents for Berenice IV in J. R. Rea, The Oxyrhynchus Papyri LV 4 and L. M. Ricketts, BASP 27 (1990) 49, 60). Since the papyrus does refer to Paniskos, but the year number is in doubt, and is presumably a single figure, the best solution is probably to assign it to a later year of Berenice IV. As far as I can see, any later year would be acceptable, unless Archelaus is proven to be a coregent with a separate dating system, in which case the choice must be either year 2 or 3. Ý

[19] Latest date of Berenice IV: gr Medinet Habu 43, 1 Tybi year 4 = 4 January 55. First dates of Ptolemy XII: BGU 8.1820 (as a past reference), 19 Pharmouthi year 26 = 22 April 55, datable to Ptolemy XII by reference to Paniskos, strategos of Heracleopolis; and SEG 39.1705, almost certainly the base of a statue of the king (Alexandria 22979) dated to 12 Pharmouthi year 26 = 15 April 55 (J. Quaegebeur, GM 120 (1991) 49 at 56; G. Bastianini & C. Gallazi, Quaderni ticinesi di numismatica e antichità classiche 18 (1989) 201; P. E. Stanwyck, Portraits of the Ptolemies 123 (E3)).

Cicero (Ad Atticum 4.10.1) writing on a.d. IX Kal. Mai. AUC 699 = 8 April 55, reports hearing rumours that the king has been restored. Since the news typically took about 6 weeks to travel from Egypt to Rome, it follows that Ptolemy XII was restored to power mid February 55. Ý

[20] There are several documents dated by both the 30th and the 1st year, between 22 Pachons = 24 May 51 (BGU 8.1829) and 14 Epeiph = 15 July 51 (BGU 8.1827), assignable to this period through their references to Seleukos, strategos of Heracleopolis. W. Otto & H. Bengtson, Zur Geschichte des Niederganges des Ptolemäerreiches 25f. n. 2, suggested these documents indicate that an ephemeral coregency was set up by Ptolemy XII shortly before his death, even though they accepted that the dates of all these documents fell after the death date of Ptolemy XII. T. C. Skeat, JEA 46 (1960) 91, argued that the proposed coregency was highly unlikely, given that the reported will of Ptolemy XII bequeathed the kingdom to the joint rule of the elder children, to be guaranteed by the Roman Senate (ps-Caesar, Alexandrian War 33). A. E. Samuel, Ptolemiac Chronology 157f., noted the date of BGU 8.1755, read by W. Schubart as 29 Thoth year 1? of Cleopatra VII as evidence supporting Otto and Bengtson's proposal, since this date falls before the death date of Ptolemy XII. However, he subsequently withdrew the suggestion (A. E. Samuel, CdE 40 (1965) 376, 391ff.), assigning BGU 8.1755 to Berenice IV, and suggesting instead that the year 30 = year 1 dates may relate to an attempt to conceal his death while Cleopatra's rule was being confirmed.

H de Meulenare, CdE 42 (1967) 297 elaborated on this proposal for a coregency by assigning two Theban ostraca, oThebes D100 (dated 2 Payni year 30) and oThebes D24 (dated 21 Pachons year 30), to Ptolemy XII, thus making their dates 3 June 51 and 23 May 51 respectively. These ostraca, together with oThebes D103 (dated Pharmouthi? year 30), refer to the office of the "tax collector of the Old District", otherwise only known from oMattha 81 (dated to year 28). oMattha 81 can only belong to Ptolemy VIII or Ptolemy XII (since Ptolemy IX did not have a year 28 = 90/89 in Egypt), and on paleographical grounds must belong to Ptolemy XII. De Meulenare reinforces this identification on prosopographical grounds. He also notes that the "Old District" itself is only otherwise known on oMattha 275 (year 28) and oThebes D19 (year 22). Hence he concludes that these ostraca all belong in a narowly defined block of time at the end of the reign of Ptolemy XII, and that oThebes D100 and oThebes D24 therefore show his regnal years in use over two months after the date of iBucheum 3, usually held to mark the terminus ante quem for his death date. Hence they prove a coregency. I find this very tenuous: a name like "the old district" is not going to be in use for just a few years, but for a long period of time, so, while accepting that oMattha 81 belongs to Ptolemy XII, I see no reason why oThebes D100 and oThebes D24 couldn't belong to year 30 of Ptolemy IX.

L. M. Ricketts, The Administration of Ptolemaic Egypt Under Cleopatra VII 12ff. collected all references for year 30 = year 1 and for year 1 as they stood in 1980 and reanalysed the data. She first confirmed that these double dates all followed the first attestation of Cleopatra VII as queen in iBucheum 13, dated 19 Phamenoth year 1 = 22 March 51. She concluded that the formula cannot represent a coregency, real or fictional. Secondly, only one other example of a "year 1" date exists during the interval March-July 51: PSI 8.969, dated 5 Epeiph = 6 July (BGU 8.1757, dated 9 Epeiph year 1, can be shown to belong to Berenice IV, and pFayum 16, dated Payni 19 year 1, could belong to Berenice IV or (more likely) Ptolemy XII). There is no ruler named on PSI 8.969, but she does not suggest that the same possibilities are open here, presumably since the letter is addressed to a Seleukos who may be identified with Seleukos the strategos of the Hermopolite nome at the end of the reign of Ptolemy XII.) Since this is very close to the end of the double-dated period it probably represent a transition to the year 1 dating. She concludes that this analysis confirms that the double dates represent a period when Cleopatra VII's rule was being confirmed.

This proposal seems reasonable. However, its premise is that iBucheum 13 is correct. This stele was written under Augustus, and it may well be that the date is retroactive; Cleopatra VII's presence for the installation may well be as fictional as the presence of Augustus himself at the installation of the next Buchis bull.

A second line of argument for a brief coregency is based on the royal names in the subterranean crypts in the Temple of Dendera. E. Winter, GM 108 (1989) 75 pointed out that in one instance, in the first western crypt, Ptolemy XII is accompanied by a Cleopatra whose name is given in a cartouche. Since she is not called Tryphaena, and since an inscription on the naos of the temple records that construction began on 14 Epeiph year 27 of Ptolemy XII = 16 July 54, i.e. after the death of Cleopatra V, this Cleopatra must be Cleopatra VII, therefore he proposes that it demonstrates a coregency. J. Quaegebeur, GM 120 (1991) 49, 60 further noted that in two instances in the first eastern crypt Ptolemy XII is accompanied by a queen whose name is omitted but is entitled "the daughter of the king" and "the eldest [daughter] of the king"; again, this can only be Cleopatra VII. Further, the king is unnamed on many of the scenes, and Quaegebeur suggests that the king so represented is Ptolemy XIII.

I find this very unconvincing. It is to be noted that the "queen" of the Denderah crypts is not called a queen. It is much more plausible to my mind that she is being presented as Ptolemy XII's female heir, not his coregent. It is clear that Ptolemy XII was already making arrangements before his death: OGIS 741 = SB 8933, dated 29 Pachon year 29 = 31 May 52, refers to at least some of his children as the Qeoi Neoi Filadelfoi (New Sibling-loving Gods). Winter argues that the subterranean crypts were all completed before the above-ground work was done. If their near-completion conicided with the news of Ptolemy XII's death, it may well be that most of the cartouches are empty simply because it was decided to advance to the next phase immediately. Ý