Ptolemy X

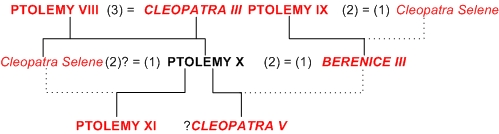

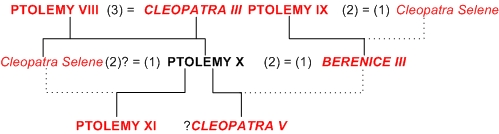

Ptolemy X Alexander I Philometor1 king of Egypt, sometimes also Philometor Soter1.1, also probably known as Kokkes or Kokke's son2 and Pareisaktos3, and probably to be identified with Ptolemy Alexas3.1; son of Ptolemy VIII4 by Cleopatra III5 date of birth unknown but possibly year 31=140/396, possibly governor of Cyprus c. July 1167, proclaimed king in Cyprus in 114/38, replaced Ptolemy IX as junior ruler under Cleopatra III in September 1079, incorporated in the dynastic cult with her at that time as the Mother-loving Saviour Gods, Qeoi FilometwreV SwthreV10, senior eponymous priest in at least years 8 and 9 = 107/6 and 106/511, became senior ruler associated with Berenice III in October 10112, expelled from Alexandria and replaced by Ptolemy IX in c. May 8813, died while attempting to invade Cyprus in late summer 88 or spring / summer 8714, allegedly bequeathing the kingdom to Rome14.1, posthumously omitted from the dynastic cult15.

Ptolemy X's titles as king of Egypt were:16

Horus nTrj-m-Vt Vnm.n-sw-@pw-anx-Hr-mdxn(t) Hwnw-nfr bnr-mrwt sxaj.n-sw-mwt.f-Hr-nst-jt.f

TmA-aHwj-xAswt jTj-m-sxm.f-mj-Ra-psD.f-m-Axt17

Two Ladies shrw-tAwj kA-nxt sxm-nHH18

Golden Horus aA-jb mrj-nTrw jty-BAqt HoA-WADtj ao.f-&Amrj-m-Htp (etc.)19

Throne Name jwa-(n)-nTr-mnx-nTrt-mnxt-Rat stp-n-PtH jrj-MAat-Ra znn-anx-n-Jmn20

Son of Re ptwlmjs Dd n.f Alksntrs anx-Dt mrj-PtH21Ptolemy X married twice and had no known liaisons.

Ptolemy X first married Unknown, here identified as his sister Cleopatra Selene22, by whom he had at least one child, Ptolemy XI23.

Ptolemy X second married his niece and probable stepdaughter, Berenice III24, daughter of Ptolemy IX25 probably by Cleopatra Selene26, by whom he probably had at least one child, a daughter27, here identified with Cleopatra V28.

[1] PP VI 14555. Gr: PtolemaioV AlexandroV. The name "Alexander" is attested throughout his reign and before, and in the classical sources (e.g. Justin 39.4). The numbering as Ptolemy X follows the convention of RE and is today standard. He is sometimes numbered as "Ptolemy IX" or "Ptolemy XI" in older works. He is usually referred to as Philometor in the papyri, and as Ptolemy X or Alexander I today. Ý

[1.1] E.g. pDion 20, iGFayum 3.209 = SEG 33.1359. Ý

[2] Strabo 17.1.8, Chronicon Paschale.

E. Bevan, The House of Ptolemy, 326 n. 2, notes that the epithet "Kokkes" is either a masculine nominative or a feminine possessive, although he favours the latter interpretation. For P. Green, Alexander to Actium, 877 n. 4, there is no doubt: the exact phrasing (o kokkhV) "is clearly a possessive". J. E. G. Whitehorne, Aegyptus 75 (1995) 55, also accepts this view. Indeed, although the possibility that the term refers directly to Ptolemy is often noted, I have not found a single scholar who accepts it. In direct support, the Chronicon Paschale names Ptolemy X as the "son of Kokke" in the 7th century AD. Bevan, loc cit, supposes that the author of the Chronicon may have inferred the relationship from Strabo -- but at the very least, it shows that he also took the modern interpretation.

If the term o kokkhV is correctly identified as a feminine possessive, it suggests that his mother was known as "Kokke". The exact meaning of the term is obscure. KokkoV means "scarlet", so A. Bouché-Leclercq, Histoire des Lagides II 95 argues that kokke refers to her presumably ruddy complexion. P. Green, From Alexandria to Actium 877 n. 4, notes that kokkoV was also a slang term for "vagina", hence proposes the translation of "the Cunt" -- with her son being a "son of a bitch". (Bill Thayer, pers. comm., points out to me a modern analogy: the French slang "coccinelle" = "queer/pansy" originally means "ladybird/ladybug", cognate with the (scarlet) cochineal beetle.) J. E. G. Whitehorne, Aegyptus 75 (1995) 55, thinks that the phrase was modelled on a phrase "Kyke's child" which occurs in a poem by Anacreon attacking an enemy of his who unexpectedly enjoyed a sudden and undeserved change of fortune, and proposes that possibly both these phrases may be translated as the "cuckoo's child", in which case, he feels, the term would not have applied to the mother. The logic in the last step escapes me -- surely it's the cuckoo herself who is responsible for introducing her child into the nest? No matter: to my mind, the term may well have meant all of the above.

Together with the epithet "Pareisaktos", it is assigned to a Ptolemy who came from Syria, melted down the golden coffin of Alexander, and was immediatey expelled by the Alexandrians. Strabo says he did not profit by this action because of this. The identity of this Ptolemy is, of couse, unclear, since this is all we know about him under these names. It is almost universally assumed to refer to Ptolemy X, but the facts are arguably consistent with Ptolemy IX, Ptolemy X or Ptolemy XII. It is also possible that the prince involved is otherwise unknown; indeed Strabo's description might even be consistent with Ptolemy "o Kokkes" being a Syrian pirate who seized the gold in a daring razzia on the city.

M. L. Strack, Die Dynastie der Ptolemäer 221, identified him as Ptolemy IX based on Josephus, Ant. Jud. 13.13.1, which briefly describes his unsuccessful invasion of Egypt from Syria in the Ninth Syrian War, about 103. Strack supposed that this invasion was the occasion of the raid on Alexandria, but Josephus makes no mention of the seizure of Alexander's coffin, a spectacular event that would be hard to ignore.

Ptolemy X appears to have raised money in Tyre to finance his return to Egypt, so the passage could quite reasonably describe a momentarily successful return to Alexandria after an initial expulsion, as proposed by J. E. G. Whitehorne, Cleopatras 175; on this scenario, Alexander's coffin was melted down in order to pay the troops. Against this, one might note that neither of our classical sources on his expulsion (Porphyry in Eusebius, Chronicorum I (ed. Schoene) 163; Justin 39.5) mention any such episode. However, the Egyptian evidence makes it clear that both these accounts are greatly simplified.

On the other hand, Ptolemy XII had a great need for money after bribing Rome for recognition, which Dio 39.12 says was the direct cause for his expulsion in 58. This would certainly explain why he might melt down the coffin. Against this, Dio's account does not mention this point, when we might expect him to do so since he directly addresses the issue of Ptolemy XII's efforts to raise money, and Strabo's text appears to imply that his king melted the coffin down immediately after arriving from Syria, whereas Ptolemy XII was not expelled for more than 20 years after he arrived "from Syria" (if indeed he did come to Egypt that way); it is necessary to interpret the text as implying expulsion immediately after the melting. Strabo 17.1.8 is followed shortly afterwards by a general overview of the Ptolemaic kings in Strabo 17.1.11 in which Ptolemy XII figures prominently as "Auletes" and which does not mention Ptolemy X. Strabo makes no attempt to connect "Auletes" to the king in question, which strongly suggests that they were two different kings; on the other hand, it is possible that this means that he gathered his information from different sources which did not make the connection for him.

The view that Ptolemy "o kokkhs" was Ptolemy X and that the term refers to his mother receives strong support from the fact that it was adopted by the Chronicon Paschale, as noted above. Almost any of the meanings discussed above could apply very well to his mother, Cleopatra III, who was certainly a ruthless operator, and who certainly played the role of "cuckoo" in her mother's nest, displacing Cleopatra II's sons in favour of her own -- and was responsible for a sudden change in the fortunes of Ptolemy X. Of course, much the same remarks also apply to her as the mother of Ptolemy IX. Whoever was the mother of Ptolemy XII, her very invisibility makes it unlikely that the Alexandrians had her in mind when they created the term, so it would have to be understood only with reference to him, as "son of a bitch" or (and only in the sense that he was illegitimate) the "cuckoo's child".

The name "Pareisaktos" (the one secretly introduced) may refer to the means by which this Ptolemy entered Alexandria to conduct his raid. It is generally understood to refer to the circumstances of the king's accession, implying an element of subterfuge. This fits quite well with Ptolemy X, who came to the throne as a result of a plot by his mother to displace Ptolemy IX. While we don't have an exact description of the circumstances of the accession of Ptolemy XII, it followed the murder of Ptolemy XI by an Alexandrian mob, so there is no particular reason, on the limited evidence we have, to suppose any element of secrecy or subterfuge. Thus, of the known Ptolemaic kings, this name would also appear to favour Ptolemy X.

Finally, there is the possibility (noted to me by M. Passehl, pers. com. Jan. 2011) that Ptolemy "o kokkhs" is otherwise unknown. If, as is universally held, the epithet involves his mother, I think this is extremely unlikely -- she should be well known, otherwise what would be the point? Hence this theory involves accepting an interpretation that is regarded to be less probable. Granted that, it cannot be positively excluded, but the fact that Strabo's story is consistent with what we know about the activities of a known king, and the assignment of the name to Ptolemy X by the Chronicon Paschale gives me no reason to consider this possibility as likely.

Clearly, the identification of Ptolemy "o kokkhs" is a judgement call. The argument for Ptolemy X depends heavily on the assignment of the Tyrian hoard to this king rather than Ptolemy XI; if this were disproved, there would be no other known basis for placing him in Syria. Nevertheless, in my opinion, the arguments for Ptolemy X are more convincing that those for either Ptolemy IX or Ptolemy XII, and I see no good reason to suppose he is an individual who is otherwise-unknown. Ý

[3] Strabo 17.1.8. The name means "the one secretly introduced" (scil. to the throne), or "the ring-in" -- J. E. G. Whitehorne, Aegyptus 75 (1995) 55. For the assignment of this epithet to Ptolemy X see discussion above. Ý

[3.1] The principal source for this name is Cicero, De lege agraria. The speech is partly concerned with claims that an Egyptian king, variously named "Alexander" or "Alexas" in the surviving MSS, bequeathed Egypt to Rome in his will. The king is named three times in the speech, once in De lege agraria 1.1 and twice in De lege agraria 2.41.

Additionally, the Bobbio Scholiast, who is dated to the fourth or fifth century, mentions "Alexas" when commenting on fragment F3 of Cicero's lost speech De rege Alexandrino, which was concerned with the same events. Finally, three of the Chronica Minora -- the Liber Generationis (4th century), the Chronicon of 334 and the Chronicon of 452 -- also know a "Ptolemy Alexas". The Chronicon of 334 knows of two kings by this name; the other two know of a "Ptolemy Alexas" and a "Ptolemy Alexander". The name is not recorded in any Greek source for a Ptolemaic king.

In the standard Latin editions of De lege agraria, the king is called "Alexander" in the first passage and "Alexas" in both mentions in the second passage. A. Clark, M. Tulli Ciceronis Orationes, collated 9 surviving codices of this speech. All but one of these are of 15th century date; the other (the Codex Erfurtensis) is from the 12th or 13th century. Two of these codices give variant forms of the two passages in question. The codex S. Marci 254 does not give the form "Alexas". Instead, it gives "regis Alexandrini" (Alexandrian king) instead of the more usual "regis Alexandri" in De lege agraria 1.1 and also calls the king "Alexander" in both instances where his name is mentioned in De lege agraria 2.41. The codex Laur.XLVIII.26 switches from "Alexander" to "Alexas" in De lege agraria 2.41.

The fact that these variants are not known in either the oldest codex or in the majority of codices studied by Clark is very suggestive, but not enough in itself to prove that the standard resolution correctly represents Cicero's original usage. That would require a reconstruction of the transmission history of the codices. I am not in a position to that. However, the occurrence of the name over a thousand years earlier in the Bobbio Scholiast, who was directly commenting on a speech of Cicero's, and in the Chronica Minora, texts that reflected a Latin tradition strongly influenced by Cicero, is, I think, strong circumstantial support for the view that Cicero called the king "Alexas". Most likely the version "regis Alexandri" in De lege agraria 1.1 is also correct, in which case Cicero knew him under both names

As to which king Cicero had in mind, there are three possibilities: Ptolemy X Alexander I, Ptolemy XI Alexander II, or a "Ptolemy Alexander III" who is otherwise unknown. The last possibility was discussed in the 19th century, but there is no good reason to believe it and several not to; it has no proponents today. Before 1967, De lege agraria was widely understood to be referring to Ptolemy XI, and still is by some, e.g. R. D. Sullivan, Near Eastern Royalty and Rome 100-30 B.C. 90 and 366 n.4. However, in that year E. Badian, RhMP 110 (1967) 178, published an influential paper arguing that the will was that of Ptolemy X, which would mean that "Alexas" was Ptolemy X. Badian's proposal is not universally accepted, but is now the orthodox view. Neither Badian nor subsequent scholars discussing the will address the significance of the name "Alexas". Indeed, Badian silently opts for using the form "Alexander" when quoting De lege agraria 2.41 at the beginning of his paper.

Aside from circumstantial arguments related to the will, which in my view favour Ptolemy X, there is also the evidence of the Chronica Minora. The Liber Generationis gives the succession order "Euergeta, Ptolemeus Alexus, Alexander frater Ptolemei Alexe, Ptolemeus Dionisius Hecate". The Chronicon of 334 gives the order "Ptolemeus Euergentis, Ptolemeus Alexi, Ptolemeus secundis Sotheris, Ptolemeus Alexi frater", and the Chronicon of 452 gives "Ptolemeus Fuscus, Ptolemeus, Ptolemeus Alexas, Ptolemeus Soter, Alexander frater Ptolemei". All these accounts are clearly confused and inaccurate (which is hardly surprising). Nevertheless, they consistently show a king known as "Alexas" as one of the two kings following Ptolemy VIII, with "Alexander", if named at all, being a later successor. They also show that "Alexas" was the brother of another king, though they conflict as to which. Both these characteristics are correct for Ptolemy X, but are not for Ptolemy XI, who does not appear to be reflected in these accounts at all. While not decisive, in view of the general inaccuracy of the lists, in my view these features strongly favour identifying "Alexas" as Ptolemy X.

Against this, M. Passehl, pers. comm., has argued strongly that the name "Alexas" must be understood as a diminutive nickname ("little" or "young" Alexander). A diminutive would be a natural nickname for a young man with the same name as his father, and therefore, in Passehl's view, it must be understood to refer to Ptolemy XI. Passehl further argues that its appearance in the Latin tradition and its absence from the Greek tradition on the Lagids indicates that it originated in Rome, which implies that it reflects personal familiarity with the king there. While there is no evidence that Ptolemy X ever visited Rome, Ptolemy XI spent several years there before his return to Egypt.

This suggestion naturally raises the questions of the significance of the name, why Cicero used it, and whether it is provably a diminutive. The name "Alexas" is very rare in the first centuries B.C. and A.D. and appears to be unknown earlier, although an Alexias was archon of Athens in the fifth century B.C. and another Alexias is known as a physician in the fourth century. A playwright Alexis, regarded in his time as the leading exponent of Athenian "Middle Comedy", is known in the fourth century B.C. The latter was born in Thurii in southern Italy.

Almost all the instances I have found of "Alexas" in the first centuries B.C. and A.D. are literary. Apart from the king in question they are:

Alexas of Heracleia (later Herculaneum), granted Roman citizenship in 99 (Cicero, Pro Balbo 50). The MS tradition shows no variation of name. To my knowledge this is the first clear occurrence of the form "Alexas", though there is one posible occurrence in the fifth century BC (see below)

- Alexas the Syrian (Plutarch, Antony 66.5), probably the same as Alexas of Lycaonia (Plutarch, Antony 72.2, 72.3), an aide of Antony's. The MS variants listed in the Bekker edition show no variants of this name. However, Josephus, Ant. Jud. 15.6.7 and Bell. Jud. 1.20.3 knows him as "Alexander".

- Alexas, husband of Salome, Herod's sister (Josephus, Ant. Jud. 17.1.1, 17.6.5, 17.8.2; Bell. Jud. 1.28.6, 1.33.6). The Niese editio maior shows the variant "Alexander" for the occurrence of the name in the two instances the name is mentioned in Bell. Jud. 1.28.6, but not otherwise. "Alexander" is used for a different individual in Ant. Jud. 17.1.2.

- Alexas Selcias, son of Alexas (Josephus, Ant. Jud. 18.5.4). The Niese editio maior shows no variation of name.

- Alexas, a zealot leader (Josephus, Bell. Jud. 6.1.8, 6.2.6). The Niese editio maior shows the variant "Alexander" for the second occurrence of the name.

Turning to collections of non-literary sources, PP and PIR2 both only know of Alexas of Lycaonia. The name is known to RE from a cameo of Julio-Claudian date, a context in which space is at a premium. P. M. Fraser & E. Matthews, A Lexicon of Greek Personal Names, record 30 instances (a small fraction of those recorded for "Alexandros"), half of which are from the Western Greek region. All but one are later than 30 BC, and the frequency of the name clearly increases in the first and second centuries AD. The sole exception is a Lucanian vase dated to the fifth century BC, which is so anomalous that one suspects a misreading.

It seems to me that there is no evidence whatsoever to support the notion that "Alexas" was a nickname or diminutive, and the case "Alexas son of Alexas" in Josephus speaks positively against the latter usage. Rather, the name seems to be a variant of "Alexander", normally but not clearly regarded as a separate name, probably originating in Magna Graecia, that started to gain currency, first amongst Hellenised non-Greeks, in the mid first century BC. The relationship between the two names seems to be similar to, for example, "James" and "Jack".

We are left without a clear explanation for Cicero's usage. There may well not be any. Since the earliest clear attestations of the name are in his speeches, it may simply reflect a naming fashion of his day that was regarded as cool. If it has any significance at all, it may be an informality intended to downplay the king's importance in the matter under discussion. The comparative material says that it does not appear to have any particular value for distinguishing Ptolemy X from Ptolemy XI, in either direction. Its persistence in late Latin-based sources for identifying a Ptolemaic king reflects Cicero's extraordinary authority as a Latin author in later times.

If one nevertheless insists on interpreting "Alexas" as a diminutive, despite the lack of support for this in the sources, we should also allow the equally-unsupported possibility that it was a diminutive of Alexandrian origin. One might speculate, for example, that it disappeared from Greek sources because it was a nickname, rather than a soubriquet (many of which are only known in unique references). There are several plausible conjectures for how such a diminutive could have been applied tor Ptolemy X. It could simply reflect the fact that he was the younger brother of Ptolemy IX. Another possibility is that the comparison was to Alexander the Great, with Cleopatra III playing the role of Olympias, a satirical reference to her control of his military efforts in the "war of sceptres" of 103 (Josephus, Ant. Jud. 13.13.1). Such punning wordplays, though more vicious (to my eyes, at least), are well known for Ptolemy VIII: "Tryphon" (Magnificient) became "Physcon" (Fatso), "Evergetes" (Beneficient) "Kakergetes" (Malificient). Ý

[4] Porphyry in Eusebius, Chronicorum I (ed. Schoene) 163; Justin 39.3. Ý

[5] Justin 39.3, 39.4. Ý

[6] If the element in his Horus name "who is associated with the living Apis upon his birthbrick" has any significant relationship to the timing of events in the Apis cult, it may relate to the installation of the Apis Kerka II in 21-23 Thoth year 31 = 17-19 October 140 (Louvre 4264 -- D. J. Thompson, Memphis Under the Ptolemies 291). This may imply that he was born in 140/39. See discussion on the chronological significance of Ptolemaic Horus names under Ptolemy VI. Ý

[7] Pausanias 1.9.2. Although the timescale of events is often unclear, the wording does suggest that he was sent there to replace Ptolemy IX as strategos, since the latter had just become king. However, W. Otto & H. Bengtson, Zur Geschichte des Niederganges des Ptolemäerreiches 172f., argued that Ptolemy X did not actually take the throne at this time, but back-dated his reign after a first attempt at taking Egypt in 110/9. Accordingly, the date 114/3 could only have the significance of representing the start of his governorship in Cyprus. This scenario was subsequently disproved.

Although his strategia is almost universally accepted, it is actually unclear whether he was governor of Cyprus. We have no contemporary evidence of him in this role. T. B. Mitford, JHS 79 (1959) 94 at 99 (no 5) reconstructed a damaged inscription as naming a strategos Helenos as tutor to Ptolemy Alexander but not as king; however, J. Pouilloux, Testimonia Salaminia 2 -- corpus épigraphique 41 (no 82) reconstructs the same inscription as naming Helenos as tutor to the king. But in either case he is not recorded as strategos. The career of Helenos is difficult to interpret from the surviving evidence, but the reconstruction suggested here is that he was strategos after Ptolemy IX and under Ptolemy X, tutor to Ptolemy X, and that the latter was never strategos. Ý

[8] Ptolemy X is not considered in the Canon of Claudius Ptolemy because his reign is circumscribed by that of Ptolemy IX. We are told by Porphyry in Eusebius, Chronicorum I (ed. Schoene) 163 that his first Egyptian year was his 8th and corresponded to year 11 of Cleopatra III, which corresponds exactly with the papyri. Hence his nominal accession year was 114/3 = year 4 of Cleopatra III and Ptolemy IX. However, W. Otto & H. Bengtson, Zur Geschichte des Niederganges des Ptolemäerreiches 172f. n. 3, argued that he had attempted to invade Egypt in 110/9, and that he had actually taken the throne on that date but had backdated his regnal years to 114/3, which they argued represented the start of his governorship in Cyprus. While scholars expressed "a certain diffidence" about this complex scenario (e.g. T. B. Mitford, JHS 79 (1959) 94, 116), it was not disproved till O. Mørkholm, Chiron 13 (1983) 69, published an analysis of coins minted at Citium found in a coin hoard found at Paphos. These included two stylistically different series of coins dated years 1-4 (series A) and 1-6 (series B). Additionally, coins of years 53 and 54 (hence of Ptolemy VIII) were included. Analysis of the obverse dies showed that one die (A64) was used for the coins of Ptolemy VIII and years 1 and 2 of series A, while another die (A72) was used for years 3 and 4 of series A and for years 1-3 of series B; further, die A72 showed progressive wearing from year 3 of series A to years 1-3 of series B. It follows that series B starts immediately following year 4 of series A. Therefore, series A is Cleopatra III and Ptolemy IX, while Series B is Ptolemy X, and he actually acceded part way through the year 114/3, though we do not know exactly when. Presumably, the trigger for his accession was Cleopatra IV's successful effort to commandeer the fleet (Justin 39.3). Ý

[9] See discussion under Cleopatra III. Ý

[10] The formula for the current rulers was left unchanged, Ptolemy X simply replaced Ptolemy IX: P. W. Pestman, Chronologie égyptienne d'après les textes démotiques (332 av. J.-C. - 453 ap. J.-C.) 68, 70, 154. Ý

[11] See sources as listed in W. Clarysse, G. van der Veken The Eponymous Priests of Ptolemaic Egypt 36. Cleopatra III herself acted as eponymous priest in year 13 = year 10 = 105/4. Clarysse and van der Veken list Helenos son of Apoll[on?]ios and Theodorus son of Seleukos as junior eponymous priests in 107/6 and 105/4; in fact both were priests of the living queen. Helenos was the governor of Cyprus under Ptolemy X while he was in exile there, while Theodorus had preceded Ptolemy IX as governor of Cyprus. See T. B. Mitford, JHS 79 (1959) 94. Ý

[12] Berenice III first appears with Ptolemy X in the dating formulae immediately after the death of Cleopatra III. Ý

[13] See discussion under Ptolemy IX; Ptolemy IX apparently returned in early 88 or possibly late 89, but documents recognising the rule of Ptolemy X in Egypt continue till October 88, and he may have briefly succeeded in recovering control of Alexandria. Ý

[14] Porphyry in Eusebius, Chronicorum I (ed. Schoene) 163, 165. Before invading Cyprus he had been defeated in a sea-battle by an Alexandrian fleet. These events are related to his 19th year as king of Egypt. E. Badian, RhMP 110 (1967) 178, supposing him to have been expelled when his dates cease in Egypt (see discussion under Ptolemy IX) and considering the time necessary for Ptolemy X to raise funds and to assemble a fleet, suggests quite reasonably that the battle was "not fought before the spring of 87". However, this model assumes that he did not leave Egypt until about the time of his last date there, 4 October 88. Since it appears that he had actually lost control of Alexandria in c. May 88, and may even have briefly recovered it from Syria, it is quite possible that he fought the war outside Egypt while his partisans continued to fight inside the country. On this scenario, he could have raised the fleet in 88 and died in late summer of that year, so that the end of his dates in Egypt represents the surrender of his partisans there on learning of his death. For his will leaving the kingdom to Rome, see discussion here. Ý

[14.1] The principal source of information about this will is Cicero, De lege agraria, with additional notes from the Bobbio Scholiast in fragments of De rege alexandrino. In De lege agraria 1.1, Cicero notes that many assert that Egypt had become Roman property through the bequest of king Alexander. In De lege agraria 2.41, he notes that L. Marcius Philippus assured him of the existence of the will of king "Alexas", and that a resolution of the senate had been passed when legates were sent to Tyre after the death of the king to recover moneys he had deposited there, considering them to be Roman property, which was understood as accepting the inheritance ("auctoritatem senatus exstare hereditatis aditae sentio tum cum Alexa mortuo legatos Tyrum misimus, qui ab illo pecuniam depositam nostris recuperarent."). What clearly emerges from this is that not only the acceptance of the bequest of Egypt but that the very existence of such a bequest was a controversial matter in Cicero's time, since knowledge of it relied on hearsay information.

The identity of the king and the date of the will was reviewed by E. Badian, RhMP 110 (1967) 178. His argument for Ptolemy X has been generally accepted, but has also been strongly challenged, most notably by D. C. Braund, PBSR 51 (1983) 16 at 24ff. The arguments have been further discussed in E. Van't Dack et al, The Judean-Syrian-Egyptian Conflict of 103-101 B.C. 156ff. The issue is subtle and complicated. However, since the date of the will has important implications for interpreting the evidence on the age and genealogy of Ptolemy XII, it is worth discussing here in some detail.

Badian notes that, at the start of the surviving portion of the speech, Cicero states that it is said by many that the will would have been effective "after the consulship of these men", who (from De lege agraria 2.56) were L. Cornelius Sulla and Q. Pompeius Rufus, consuls in AUC 666 = 88. Therefore any will was effective in 87 or later. If news of the death of Ptolemy X was known in Rome in 88, then the will can only be that of Ptolemy XI. However, if Ptolemy X did not die till 87, or if news of his death did not reach Rome till then, he remains a viable candidate.

His last certain date in Egypt is 21 Thoth year 27=30 = 4 October 88 = prid Non Oct or ad IV Kal Nov A.U.C. 666. Even if he died a month before this date, the timing is very tight for the news to reach Rome, for the senate to debate it and for consuls to do anything about it all before the end of the consular year. Thus I think that Badian's point is sound, regardless of the exact date of his death.

Having established his potential candidacy, Badian proceeds as follows:

He argues that in De lege agraria 2.41 Cicero means that there was a senatus auctoritas to authorise the sending of legates to collect a large sum of money "Alexas" had left in Tyre that was held to be Roman, and that the money was actually recovered by a delegation sent there. Badian notes that the reference to a senatus auctoritas indicates a vetoed senate decree, but argues that the sending of legates could still have been done by consular administrative action. He suggests the matter was remembered because of the precedent set by the consuls in overriding a vetoed decree, and argues that the fact that the money was recovered in spite of the veto indicates that it was clearly regarded as an urgent matter.

A. N. Sherwin-White, Roman Foreign Policy in the East 264, holds that Badian's view implies that the vetoed decree included acceptance of the inheritance, but that this is a mistranslation of Cicero. Rather, the senate had only authorised the despatch of legates to collect the money, but that Cicero was aware of an argument that the decree authorising that action could be construed as entering into the inheritance. In support of this she notes that in De rege Alexandrino F5, Cicero notes that only the money was claimed by the senate.

D. C. Braund, PBSR 51 (1983) 16 at 25, argues that, since the legates were actually sent to collect the money, the senatus auctoritas must have been issued after their despatch, and therefore the decree must actually have declared that this action constituted acceptance of the inheritance. Chronologically, this means, at least in principle, that the decree could have been passed (and vetoed) any time after the money was claimed.

E. Van't Dack et al., The Judean-Syrian-Egyptian Conflict of 103-101 B.C. 158 n. 191 notes that Sherwin-While has misunderstood Badian and in fact the two are in violent agreement: the decree was only concerned with the collection of the money. He further notes that Braund's argument implies that there were in fact two senate decrees: a senatus consultum authorising the collection and the senatus auctoritas formally accepting the inheritance and, by implication, annexing Egypt.

I have to agree Badian and Van't Dack on with this. Cicero's text clearly associates the collection of the money closely with the vetoed decree, whatever else that decree might have said or implied about entering into the inheritance. There is therefore no reason to dissociate the date of the decree from the date the money was collected. Further, the collection of the money despite the vetoing of the decree does indicate that it was considered an urgent matter. Hence Braund's attempt to separate the two dates seems to me to be unfounded.

It follows from Badian's argument that if "Alexas" was Ptolemy XI then the veto must have been exercised in 80/79. He points out that it is impossible to believe that a tribune would risk vetoing a senate decree issued at the height of the Sullan dictatorship.

D. C. Braund, PBSR 51 (1983) 16 at 25 argues that, assuming the will was that of Ptolemy XI, the decree can be dated at anytime between 80 and 74 -- and could even be later. He cites Cicero, In Verrem 2.1.155, as evidence that the tribunician veto was exercised in 75, and therefore could have been exercised at other times in this period. Therefore there is no reason to accept Badian's argument that the veto implies the will was not that of Ptolemy XI.

This argument depends on separating the date of the decree from the death of the king. However, Cicero is clear that the events happened "cum Alexa mortuo". Since any inheritance is only entered into after the death of bequestor, the only reason to mention the point is to associate the events. That is, Cicero is specifically tying the recovery of the money and the passage of the vetoed decree to a period shortly after the death of the king.

In any case, these events are unlikely to have happened after 75, since Cicero himself became a senator in that year. A striking feature of De lege agraria 2.41 is the extent to which he relies on the testimony of L. Marcius Philippus, both for the existence of the senatus auctoritas and even for the existence of the wil. If the senatus auctoritas was passed after 75, Cicero should have been in a position to vouch for it on personal authority.

By contrast, if "Alexas" was Ptolemy X, the date of the vetoed decree must be c. 87/6. The circumstances at this time, of the looming or actual civil war between the Marian/Cinnan and Sullan factions, and the impending Mithridatic War, made it impossible to enforce acceptance of the bequest of Egypt, but the money at Tyre would be extremely valuable to either side. This explains why the senate and the consuls focussed on the money. Badian suggests there was a race to get the money between a senate legation and Sulla's envoy Lucullus, who toured the Phoenician coast with an Egyptian escort (Plutarch, Lucullus 3.2). According to Schol. Bobb. on Cicero, De Rege Alexandrino F3, the money was recovered and sent to Rome, suggesting to Badian that the Cinnans won the race.

Against this scenario, D. C. Braund, PBSR 51 (1983) 16 at 27 n. 44 notes that there is no evidence that Lucullus was engaged in a race to get the money, having stopped off first in Crete, Cyrene and in Egypt. Mark Passehl, pers. comm., further argues that the seas were so unsafe at this time (as evidenced by Lucullus' need for an escort) that it was not worth the risk to attempt to retrieve the money.

It seems to me that Lucullus' route proves nothing. It was the Marian/Cinnan side that was after the money, ex hypothesi -- it is perfectly possible, for example, that Sulla and Lucullus overlooked it till it was too late (though Ptolemy IX, who was surely aware of the alleged will, might well have drawn it to Lucullus' attention since it was probably in his interest that the money be collected -- it could well be argued that it represented a quitclaim).

Passehl's point about the state of the seas is fair, but hardly decisive. This could have been a consideration behind the veto (or a justification; the political allegiance of the tribune is the more likely reason). Given the state of crisis, if the sum involved was sufficiently large, it may well be that the consuls decided it was worth overriding the veto even though it was playing a long shot -- that happened to pay off.

Braund doesn't address Badian's argument for the case that a veto in 87/6 is intelligible. Again with E. Van't Dack et al., The Judean-Syrian-Egyptian Conflict of 103-101 B.C. 159, I have to agree that a serious disagreement within the Roman government on the issue, which is reflected in the fact that the collection went ahead despite the veto, makes a lot more sense in 87/6 than in 80/79.

Badian further points out that it makes no sense for Ptolemy XI, who was going to assume the Egyptian throne at the invitation of the Alexandrians, to have detoured to Tyre to deposit a large sum of money there.

D. C. Braund, PBSR 51 (1983) 16 at 27 n. 44, notes that we don't know why either king should have deposited money at Tyre. He suggests that it was a nest-egg in case the king should be expelled from Egypt, the equivalent of the modern Swiss bank account. He supposes it was "a precaution necessitated by the king's difficulties at Alexandria: the very forces that encouraged the making of a will."

With Badian, I agree this makes no sense. Ptolemy XI needed no money for his return, since he went by invitation, and his reign was so brief -- 18 or 19 days alone, at most a month or two with Berenice III -- and went bad so quickly, that it hardly seems likely that he would have had time to acquire such a nest egg, let alone to make arrangements to send it out of the country.

For the same reason I can't see that he would have had incentive to make a will or time to perfect it during his reign. To my mind, a will by Ptolemy XI giving rights to Rome makes most sense if it was made before he left Rome, giving Sulla a surety in case he did not deliver the return that Sulla apparently expected (Appian Civil Wars 1.102) -- but then, there should not have been any doubt in Rome about the very existence of the will, nor about its contents, which would have become public knowledge on his death. However, it is very clear from Cicero's speech that the existence of the will was very much in dispute, since he has to rely on the authority of Philippus to attest to it. Also, Sulla made no attempt to execute any will.

Ptolemy X, on the other hand, was fighting Ptolemy IX, who controlled the country, and needed to raise the fleet that he eventually led to his death. Phoenicia was a natural place to do that, and Roman financiers in the East a natural resource to turn to. Badian proposes that Ptolemy X raised the capital to finance his fleet by using his rights to the Egyptian throne as collateral, with reversion being expressed through the will; in effect he positioned the Roman state as his guarantor.

D. C. Braund, PBSR 51 (1983) 16 at 27 n. 44, argues that such a will would have been poor collateral for a private loan, citing the similar loan made by C. Rabirius to Ptolemy XII, raised in expectation of success and repayment from the revenues of Egypt. He also argues that Ptolemy X couldn't have both deposited the money in Tyre and used it to buy Tyrian mercenaries.

Certainly, the money would have been raised in expectation of success and repayment from the revenues of Egypt. However, Badian's arguments about the value of the collateral (E. Badian, RhMP 110 (1967) 178 at 187) seem to me to be sound: by making the state his guarantor, Ptolemy X also covered the case of failure, which must have been a concern to his potential backers. In that case they could take the will to Rome, and either have the state annex Egypt, with repayment according to the original plan, or argue that the state itself had assumed the debt. In the event, the state (typically) screwed the lenders by sequestering the loan -- which may have been a factor in the veto.

Or at least the unspent balance of the loan. To Braund's second objection, it is hardly likely that Ptolemy X would have used all the proceeds at once.

Since Ptolemy X ruled Egypt for 19 years and Ptolemy XI for 19 days, an unqualified reference to a "king Alexander" is far more likely to refer to Ptolemy X than Ptolemy XI.

D. C. Braund, PBSR 51 (1983) 16 at 25 notes that Ptolemy XI very probably spent several years in Rome before returning to Egypt, and was quite likely well known there. Hence the length of his reign is not an obstacle to assuming he was well known; he was probably better known than his father.

This is a fair point, though, Braund's opinion to the contrary notwithstanding, it hardly rules out Ptolemy X as a candidate. It just places them on equal footing.

Cicero cited the authority of L. Marcius Philippus, cos. 91, for knowledge of the senatus auctoritas which, being vetoed, was not recorded. Badian argues that Philippus was the only surviving consular from 86 with authority to vouch for the will when Cicero entered the senate in 75, and hence that the decree must be from that time rather than around 80/79.

D. C. Braund, PBSR 51 (1983) 16 at 26 notes that Cicero could have cited Philippus for other reasons, e.g. because he took a particular interest in the matter, for unspecified reasons.

This is a fair point as far as it goes. It may be, for example, that Philippus himself was one of the lenders screwed by sequestration, or that he was the originator of the argument that sequestering the loan amounted to entering into the inheritance, i.e. that he was a leading proponent of annexation based on this event. However, it is very striking that Philippus' statements are the only evidence cited, not only for the senatus auctoritas, but also for the very existence of the will -- and that Cicero does not himself endorse these statements.

As well as objecting to Badian's arguments as discussed above, Braund makes two additional arguments in favour of Ptolemy XI rather than Ptolemy X:

If, as Badian argues, acceptance of the inheritance had been vetoed, then Sulla's support of Ptolemy XI made Egypt that king's possession to bequeath. Anyone trying to reactivate a cancelled will of Ptolemy X would have been answered simply by pointing to the decree cancelling the bequest, but it appears this argument was never made. Hence the king in question must be Ptolemy XI.

But it is very unclear that the vetoed decree concerned actual acceptance of any bequest, and Badian does not argue it did. It appears, rather, that Egypt had been been in effect pledged as collateral for a loan, and the argument was, in effect, about whether the death of the king without the repayment of the loan triggered a transfer of ownership of the collateral. If viewed in this perspective, failure to take the collateral did not equate to giving up rights to it; rather, by giving the throne to Ptolemy XI the Romans were giving the debtor's heir a chance to repay his father's debt. Similarly, Sulla made no attempt to accept the inheritance in 80, but the Roman right to enter into an Egyptian bequest was still considered viable by its proponents 15 years later.

In short, the actual nature of the "will" is very unclear, and it is rather dangerous to rely too heavily on assumptions about it when making chronological inferences.

If the will was that of Ptolemy X, it was unique amongst known royal wills bequeathing kingdoms to Rome in that he is the only example of a king who had an heir at the time of its drafting.

E. Van't Dack et al., The Judean-Syrian-Egyptian Conflict of 103-101 B.C. 160 notes that in fact the situation was very uncertain, since Ptolemy XI was a hostage of Mithridates VI at the time -- there was no assurance that he would ever be in a position to claim the throne. Given the precedent of the will of Ptolemy VIII willing Cyrene to Rome if he died without heirs, it is likely that Rome only inherited if there was no heir. These considerations suggest that Sulla may have considered his support of Ptolemy XI's succession as authorised by the will.

Which is, I think, a sufficient answer, if in fact there was a formal will bequeathing Egypt to Rome. It may further be noted that the installation of Ptolemy XI could also have been seen as an opportunity for any surviving lenders to recover their investment -- and their failure to do so because of his early death may have been a factor delaying Roman recognition of Ptolemy XII.

In my view, at no point does Braund's argument amount to creating "significant difficulties" for Ptolemy X, as he claims. At best, he shows that the will could also have been that of Ptolemy XI. In fact, on the significant points -- the date and nature of the veto, and the motives for the will and the deposit at Tyre -- it seems to me that Badian's case is by far the stronger. To his arguments one might also add Suetonius, Caesar 11, which evidently refers to the debate over the will that occurred in 65 (although he clearly does not understand the context of the debate) in terms of a king who had been deposed (as was Ptolemy X), not one who had been murdered (as was Ptolemy XI).

M. Passehl, pers. comm, has raised the additional argument that the name "Alexas" used by Cicero must be understood as a diminutive, which makes sense applied to a homonymous son of Ptolemy X, but not to the king himself. For the evidence related to the name, see discussion here.

There is one further set of evidence to discuss on this convoluted matter. Proposals have been made to trace the proceeds of the Tyrian hoard through fiscal and numismatic evidence. All proposals to date are based on the assumption that the hoard belonged to Ptolemy X.Whatever the identity of the king, it appears that the hoard was recovered but that the creditors were not paid off, and this is the reason why there was pressure for a Roman claim to Egypt. This scenario clearly requires that the creditors were stiffed by the government, who sequestered the Tyrian hoard for its own purposes. As evidence of this, E. Badian, RhMP 110 (1967) 178 at 189, notes that Velleius 2.23.2 states, with disapproval, that Valerius Flaccus, cos. suff. 86, remitted three quarters of all debts. Badian suggests that the point of this Lex Valeria was to absolve the treasury from liability for the sequestered funds.

The obvious difficulty with this explanation is that the Lex Valeria applied to all debtors. C. T. Barlow, AJP 98 (1977) 290 at 299, notes that the financial system in the period following the Social Wars was in a state of near financial crisis, and that the effect of the law was "to assure debtors that their estates would not be seized by panicky creditors and sold with undue haste at a fraction of their real value." This explanation, or something like it, sounds far more plausible -- and responsible -- than Badian's.

M. H. Crawford, Roman Republican Coinage (RRC) II 605, associates this event with issuances of denarii struck in 86-5 by three different moneyers and marked EX A(rgentum) P(ublicum). This is an unusual legend, especially since all official mintings were presumably from the public silver. Crawford identified a total of 8 such issuances; other numismatic commentators have proposed or identified others. Crawford dates the first four to 102/00, a period in which, he argues (citing Appian, Civil Wars 1.29-31), the government was required by popular pressure to provide especial recognition of the sovereignty of the people. Crawford has no explanation for the fifth, issued around the time of the Social War. As to the three issues of 86/5, Crawford supposes they were minted from the Tyrian hoard and suggests that "the unusual origin of the issues" was important enough to justify the legend.

It seems to me that the logic of Badian's argument suggests a slightly different explanation: that the state was asserting its ownership of specie that was in dispute.

Be that as it may, several alternative explanations have been offered for these issuances. K. Pink, The Triumviri Monetales and the Structure of the Coinage of the Roman Republic, 56ff., argued that the marked coins were minted from bullion kept in the treasury when there was a shortage of coinage, under the Lex Papiria of 89, but this does not explain the earlier issues. H. B. Mattingly, AIIN 29 (1982) 9 at 22, suggested that the marked coinage was minted from bullion that was intercepted by the mint before it passed through the treasury, so that treasury accounts could be reconciled. C. T. Barlow, AJP 98 (1977) 290, in a study of the operations of the sanctius aerarium, concluded it was a special reserve fund created after the Gallic sack of Rome, intended for use only in funding defence against a future Gallic emergency. He then correlated the EX A P issues with actions possessing a Gallic aspect. For the issues of 86/5, he noted that Valerius Flaccus had become governor of Transalpine Gaul in 86, and had there engaged in actions that resuted in his being awarded a triumph in 82. He proposed that EX A P marked withdrawals of bullion from these special reserves of the sanctius aerarium.

All these explanations (including Crawford's) assume that the marking EX A P marked coins made from bullion that came from one special source or another. The key observation on this issue was made by T. V. Buttrey in P. H. de Ruyter, NC 156 (1996) 79-147 at 112-113. De Ruyter's article is an extremely detailed die study of the coinage of L. Julius Bursio, one of the moneyers who appears to have issued the EX A P coinage in 86/5 (the issues themselves are unsigned). Buttrey noted that de Ruyter had proved that the EX A P coins are intermingled with Bursio's regular issues, sharing die pairings with them, in an apparently random fashion. If the bullion for the EX A P coins came from any single source, whether it be the Tyrian hoard, the treasury, the sanctius aerarium, or anything else, we would expect them to have been coined together, or largely so, not mixed in with other bullion but marked in such a way that it could be separately identified as it came to be coined, which is what the evidence seems to require.

Bearing this in mind, D. B. Hollander, AHB 13 (1999) 14 at 23, suggests that the mark relates to the use of the coinage rather than its source. He suggests that it was exchanged for bullion acquired from private sources, and was marked so that the mint and the source of bullion could trace the payments and the value of the bullion so exchanged. This explanation has the great merit that it separates the marked coins from any bullion it may represent, and seems plausible to me. However, since it appears that the state had simply sequestered the Tyrian hoard, it also implies that the EX A P coins have no connection to it.

Whatever the significance of the EX A P markings, Buttrey's analysis of de Ruyter's results seems to me to be a decisive argument against Crawford's proposal.

L. Pedroni, Pomoerium 3 (1998) 87, sought to identify the Tyrian hoard by looking for coinage bearing symbolism with Ptolemaic associations. He drew attention to coinage with double cornucopiae, a common symbol on Ptolemaic coinage but extremely rare in Roman; in particular he noted a rare Sullan issue of aurei and denarii signed by an anonymous quaestor ("Q"), RRC 375 = Syd. 755 ("Syd" = E. A. Sydenham, The Coinage of the Roman Republic). These coins are normally regarded as Sullan issues, probably minted under the authority of Lucullus, in the mid-late 80s, most probably in Greece. Pedroni suggested Ptolemaic connotations for the other two coins: RRC 308/4 = Syd. 568b+765+766, an uncia issued by M. Herennius in c. 108/7, who came from a family with epigraphically well-attested connections to North Africa, and RRC 474/7 = Syd. 1005, one of a series of sestertii issued by L. Valerius Acisculus in connection with Caesar's victory games in 45, which of course celebrated, among other things, his victory in Egypt. He argued that RRC 375 should be regarded as one of the earliest Sullan issues, minted by Lucullus in 88/7 (when he was in fact quaestor) to fund Sulla's expedition to Greece. Supposing that Ptolemy X had died in October 88, he estimated a schedule for the news reaching Rome and for the senate to have authorised recovery of the Tyrian hoard before the end of that Roman year, and for the recovery to have been executed.

This proposal seems to me to be entirely without basis. Pedroni gives no reason why we should expect to identify the proceeds of the Tyrian hoard at all, nor why we should expect to find Ptolemaic symbolism in Roman coinage -- no literary passages or analogous coinage with motifs that can be firmly tied to Roman interactions with other states, for example. Besides, double cornucopiae are hardly unique to Ptolemaic coinage of the era -- this example is from Bruttium, in southern Italy (thanks to Phil Davis for the pointer).

As to the argument itself: the Ptolemaic associations of the other coins are very forced. The basis of the claimed Herennius link to the Ptolemaic kingdom is so vague and indirect as to be meaningless. None of the other coins in the Acisculus series have specific associations with the subjects of Caesar's triumphs -- Gaul, Egypt, Pontus and Africa -- so there is no reason to believe RRC 474/7 does either.

Pedroni's reconstruction reverses the roles of the parties in Badian's. In order to suppose that the state acquired the money to fund Sulla's expedition, Pedroni has to assume the earliest possible death date for Ptolemy X, in October 88, and the fastest possible transmission time, for a decision to be made while Sulla was still consul, at the latest by 27 December 88. While it's barely possible, it's very improbable, and given that Pedroni has essentially presented no credible evidence for it, there seems no reason to consider it. More seriously, and in my view fatally, it directly contradicts Cicero's statements in De lege agraria 1.1+2.56, discussed above, that the will only became effective after Sulla's consulate. Further, Appian, Mith. 4.22, emphasises the extreme shortage of funds available to finance Sulla's expedition, so bad that it was necessary to raid sacred treasures left by Numa Pompilius. It is hard to believe that he would not have mentioned the Tyrian hoard had it providentially become available at this time.

In short, none of these fiscal or numismatic arguments for dating the will by tracing the proceeds of the hoard are remotely convincing. In my opinion none of are more than wishful thinking. Ý

[15] See e.g. the cult listing at the temple of Kom Ombo under Ptolemy XII. Ý

[16] Transliterated from J. von Beckerath, Handbuch der ägyptischen Königsnamen (2nd edition) 242 (10), including the "etc." under the Golden Horus name, with additional commentary in R. K. Ritner in "Perspectives on Ptolemaic Thebes" (forthcoming); Ritner's notes on the correct transliterations and translations of the Horus Name and the Throne Name are incorporated here. Minor variants recorded by von Beckerath are omitted. C. R. Lepsius, Denkmäler aus Aegypten und Aethiopien Text IV 68 = H. Gauthier, Livre des Rois d'Égypte IV 386 (LXXXVII) (again including the "etc." under the Golden Horus name -- surely this wasn't in the original Egyptian??). All titles are recorded in inscriptions on the exterior north face of the protective wall of the temple of Edfu. The mention of "Alexander" in the Son of Re name ensures that these titles belong to Ptolemy X. Ý

[17] "Godlike in his mother's love, who is associated with the living Apis upon his birthbrick, the perfect youth, pleasant in his popularity, who his mother placed upon the throne of his father, who is strong in strategy(?), who defeats foreign lands, who lights up the horizon with his conquering power like Re". For the reasoning associating this name with Ptolemy X, see discussion above. Ý

[18] "Who pleases the two Lands, the strong bull, powerful forever". For the reasoning associating this name with Ptolemy X, see discussion above. Ý

[19] "Who is great in heart, beloved of the Gods, master of Egypt, who takes the two crowns into his possession, who brings peace to Egypt (etc.)". For the reasoning associating this name with Ptolemy X, see discussion above. Ý

[20] "The heir of the Beneficient God and the Beneficient Goddess and female Re, who is the chosen of Ptah, who brings forth the order of Re, the living sacred image of Amun". For the reasoning associating this name with Ptolemy X, see discussion above. Ý

[21] "Ptolemy called Alexander, living forever, beloved of Ptah". For the reasoning associating this name with Ptolemy X, see discussion above. Ý

[22] See discussion under Cleopatra Selene. Ý

[23] Porphyry in Eusebius, Chronicorum I (ed. Schoene) 165. On the possibility of additional children, see discussion under Berenice III. Ý

[24] Porphyry in Eusebius, Chronicorum I (ed. Schoene) 165. Ý

[25] Pausanias 1.9.3, Porphyry in Eusebius, Chronicorum I (ed. Schoene) 165. Ý

[26] See discussion under Berenice III. Ý

[27] Porphyry in Eusebius, Chronicorum I (ed. Schoene) 165; see additional discussion under Cleopatra V. On the possibility of additional children, see discussion under Berenice III. Ý

[28] See discussion under Cleopatra V. Ý

Update Notes:

11 Feb 2002: Added individual trees.

25 Feb 2002: Split into separate entry.

23 Aug 2003: Added Xrefs to online Justin

23 Oct 2003: Completed discussion of the identification of "king Alexas" with Ptolemy X.

24 Feb 2004: Added Xref to online Strabo

13 Sep 2004: Add Xref to online Eusebius

14 Oct. 2004: Upgraded "Alexas" discussion to take account of theories of "Ptolemy Alexander III".

26 Oct 204: Extended discussion of the will of Ptolemy X in response to critique by Mark Passehl.

9 Dec 2004: Added discussion of the assignment of "o Kokkes" and "pareisaktos" to Ptolemy X rather than Ptolemy XII

11 Mar 2005: Added Greek transcription; noted that Mørkholm's analysis that Ptolemy IX recaptured Alexandria in 88 allows Ptolemy X to die that year

18 May 2005: Separated "Alexas" from the will; extended discussion of the name "Alexas".

20 May 2005: Added discussion of numismatic arguments for tracing the Tyrian hoard (thanks to Renzo Lucherini and Phil Davis)

27 May 2005: Further discussion of "Alexas" (thanks to Christian Settipani for noting onomastica)

17 Dec 2005: Note why the senatus auctoritas accepting Egypt as a bequest must have been passed shortly after the death of Alexas.

23 Dec 2005: Correct statement on manner of his death: we don't actually know that he drowned.

24 April 2006: Refine discussion of Ptolemy X as governor of Cyprus in light of additional considerations on Helenos and Ptolemy IX

16 Sep 2006: Added link to Packer Humanities DB, Canon at Attalus

17 Nov. 2007: Adjust titulary to reflect Ritner's corrections and commentary

4 Dec 2010: Fix broken Perseus links

29 Jan 2011: Expand Kokke discussion to include the Chronicon Paschale and the remote possibilities that Ptolemy "o Kokkes" is Ptolemy IX or otherwise unknown.

29 Jan 2011: Add "Philometor Soter" to documented titulary.Website © Chris Bennett, 2001-2011 -- All rights reserved