Ptolemy Memphites

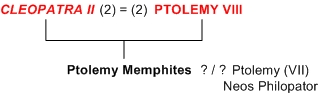

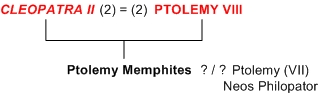

Ptolemy Memphites1, son of Ptolemy VIII and Cleopatra II2, born between late 144 and mid 1423 declared crown prince shortly before September 1424, probably not sent to Cyrene5, probably eponymous priest in year 36 = 135/45.1, taken to Cyprus by his father when he fled there in 1306, probably not declared coregent at about this time7, was murdered by his father between March and September 1308, here identified with Ptolemy VII Neos Philopator9, incorporated in the dynastic cult between Mecheir and Pharmouthi year 52 = c. March-May 118 as the New or Young Fatherloving God, QeoV NeoV Filopatwr10.

[1] PP VI 14552. Gr: PtolemaioV o MemfithV. He was born while Ptolemy VIII was being crowned in Memphis, and Ptolemy named him Memphites after the city "in which he was performing sacrifice when the child was born" (Diodorus 33.13). He is otherwise unnamed in the classical sources, however is possibly identified with the "king Ptolemy son of king Ptolemy Euergetes" of OGIS 144=iDelos 1530 and almost certainly identified with Ptolemy the heir of the king shown with Ptolemy VIII and Cleopatra II in reliefs on the exterior east and west walls of the naos of the temple of Edfu (S. Cauville & D. Devauchelle, RdE 35 (1984) 31, 51), hence his given name was almost certainly "Ptolemy" -- as one would expect. Ý

[2] Diodorus 34/5.14, Justin 38.8. Ý

[3] The temple of Edfu was consecrated on 18 Mesore year 28 = 10 September 142. The reliefs on the east and west wall of the naos showing this event contain two scenes of Ptolemy VIII accompanied by a queen and a child. On the east wall the child is called the heir of the king, borne to the queen, the king's eldest son, beloved of king Ptolemy, the god Euergetes. Although Ptolemy IX had probably been born by this date, Cleopatra III was not yet queen, so the queen shown must be Cleopatra II in each scene. The son on the east wall must therefore be Ptolemy Memphites (S. Cauville & D. Devauchelle, RdE 35 (1984) 31, 51 -- the son on the west wall, called "the living ka of the king", is probably his half-brother Ptolemy, the younger son of Ptolemy VI, possibly recently deceased). Hence he was born at the absolute latest by summer 142. Diodorus 33.13 reports that he was born at the time of Ptolemy VIII's consecration as king in Memphis, which probably took place at the first possible moment. The evidence suggests that Ptolemy VIII did not marry Cleopatra II immediately on his accession, so the earliest date for this is mid-late summer 144. A date of 144 or 143 is usual in the literature (e.g. J. E. G. Whitehorne, Cleopatras 109); while the above analysis shows it could be a little later, this is almost certainly correct. Ý

[4] In any case no later than the consecration of the temple of Edfu on 18 Mesore year 28 = 10 September 142 where he is named as heir to the king. However, Ptolemy, the younger son of Ptolemy VI and Cleopatra II, was eponymous priest, and therefore heir apparent, at least as late as August 143. Ý

[5] Justin 38.8.12 says that Ptolemy VIII summoned his eldest son from Cyrene and killed him. This son is widely identified as Memphites, but Justin's text appears to distinguish them. Huss has plausibly conjectured that he is Ptolemy, the younger son of Ptolemy VI; see discussion here. Ý

[5.1] pTebtunis III 810, dated to 7 Epeiph year 36 of Ptolemy VIII = 29 July 134; the dating is certain from the mention of "Cleopatra the Sister" in the dating formula.

The exact identity of the son involved is not clear. The papyrus was reconstructed as naming "[Ptolemy bor]n to king Ptolemy and queen [Cleopatra the wife] as the eldest son", i.e. Ptolemy IX. W. Otto & H. Bengtson, Zur Geschichte des Niederganges des Ptolemäerreiches 46 n. 2 gave the following arguments against the possibility that the papyrus named Memphites: (a) If it had been Memphites then it would not have been necessary to specify which of the queens Cleopatra was his mother, since Memphites was chronologically the eldest son of the king; (b) even if we suppose that the queen should be restored as [Cleopatra the sister] rather than [Cleopatra the wife], it is highly unlikely that Cleopatra II had a second son by Ptolemy VIII, thus it would not have been necessary to specify that Memphites was the eldest son of Cleopatra II.

These arguments were generally accepted and seemed reasonable to me until new evidence was published recently. However they were not universally agreed, and were rejected by M. Chauveau, RdE 51 (2000) 257 n. 6, as inconclusive, though neither point was specifically refuted. Chauveau preferred to make the priest Memphites, but gave no positive reason for doing so.

New evidence emerged on the point in 2004. C. di Cerbo, in F. Hoffmann & H. J. Thissen (eds.), Res Severa Verum Gaudiam 109 at 116, noted that the unpublished papyrus pdem Tebt. 5944, identifies the previously-unknown eponymous priest of year 37 = 134/3 as Ptolemy, son of Ptolemy VIII and Cleopatra III. While this could theoretically refer to Ptolemy X, it is almost certainly a reference to the elder son, Ptolemy IX.

At this time, it is very rare for the priest of the dynastic cult to be the same man (or boy) two years in a row, and when it does happen the fact is usually noted. Accordingly the priest of year 36 is almost certainly a different son, and, accepting Ptolemy IX as the priest of year 37, Memphites is the only available candidate. Ý

[6] Justin 38.8, Diodorus 34/5.14. On the date of Ptolemy VIII's exile to Cyprus see discussion under Cleopatra II. Ý

[7] He has been proposed as a coregent of both Ptolemy VIII and Cleopatra II at this time.

The evidence argued to show Memphites as a coregent of Ptolemy VIII is OGIS 144 = iDelos 1530, a dedication to Cleopatra III by a "king Ptolemy son of king Ptolemy Euergetes in honour of queen Cleopatra Euergetis my father's wife, my cousin". This is generally agreed to be Memphites, though the date at which he is supposed to have become coregent is unclear. W. Otto & H. Bengtson, Zur Geschichte des Niederganges des Ptolemäerreiches 220 n. on 62 n. 2, suggest that he was already coregent when shown on the naos at Edfu, even though he is only named there as heir apparent, because he is also called QeoV EuergeteV. J. E. G. Whitehouse, Cleopatras 118, supposes that Ptolemy VIII used the offer of association in the kingship to lure him to Cyprus. If in fact OGIS 144 is evidence of coregency, the general absence of references to him in the dating formulae (unlike, e.g., Ptolemy V as a minor coregent under Ptolemy IV) would incline me towards Whitehorne's position. However, R. S. Bagnall, Phoenix 26 (1972) 358, points out that Ptolemy Apion was also (and more certainly) a king, son of Ptolemy VIII Euergetes, and cousin of Cleopatra III, whereas Memphites was her half-brother. I do not think the last point is a significant objection to Memphites, because Memphites was indeed a cousin of Cleopatra III through their fathers, and this would probably have been the more politic relationship to stress. But the fact that Memphites is not otherwise attested as a king inclines me to favour the assignment of the inscription to Apion. Also in favour of this ascription is the fact that the dedication is to Cleopatra III, not to Ptolemy VIII, who is not obviously named as a living king.

The proposal to make Memphites a coregent of the rebellious Cleopatra II in absentia is advanced by P. Green, From Alexander to Actium 540; he does not cite evidence or argument. Presumably this is based on Justin 38.8.12, which says that Ptolemy VIII summoned his eldest son from Cyrene to Cyprus and put him to death so that the Alexandrians could not proclaim him king. But it is not certain that this son was Memphites, and in any case Justin does not say that Memphites was proclaimed king, only that Ptolemy VIII didn't want to take the risk that they might; in other words, Justin actually says the opposite of what Green infers. Also against the idea is the dating formula used by Cleopatra II in rebellion. If UPZ 2.217, dated 29 Phaophi year 2 of Cleopatra II, is correctly assigned to 22 November 131 rather than 22 November 130, then she was using her own regnal years before the fall of Alexandria, and apparently intended to be sole monarch. Nor can the incorporation of Memphites into the dynastic cult be used to argue that he was recognised as a coregent; the dating of this clearly indicates it took place as part of the general peace settlement of 118. While Green's idea is certainly not impossible, at this time it completely lacks an evidentiary basis. Ý

[8] Justin 38.8, Diodorus 34/5.14. The event is dated by Livy Periochae 59.14 and Orosius 5.10, assumed to be quoting a lost book of Livy, to the consulship of Perpenna, March 130 - March 129. According to these sources Ptolemy VIII had his son dismembered and his head, hands and feet sent to Alexandria to be presented to Cleopatra II as a birthday present. Since Alexandria fell to Cleopatra II in year 2 = year 40 = 131/0, Memphites was most likely killed between March and September 130. Ý

[9] PP VI 14550. The existence of Neos Philopator became known in the 19th century through his inclusion in the dynastic cult after 116. His identity has been a matter of dispute ever since.

M. L. Strack, Die Dynastie der Ptolemäer 47ff., 177ff., argued that he was a younger son of Ptolemy VIII and Cleopatra II. His inclusion implied to Strack that he was either an antiking (subsequently legitimised) or a coregent. He noted certain Cypriote coins (J. N. Svoronos, Die Münzen der Ptolemäer Nos 1526 (pl. 52b.22), 1565 (pl. 54a.2) and 1613 (unillustrated)) which appear to be dated to year 50 and year 1, and argued that they implied a coregency in that year. Since Justin 39.3 says that Ptolemy VIII gave Cleopatra III the right to chose which of their sons should rule after his death, the coregency was not active at that time, so Neos Philopator cannot be Ptolemy IX or Ptolemy X, but must have predeceased Ptolemy VIII. At that date, he must a son of Ptolemy VIII, either a younger son of Cleopatra II or an older son of Cleopatra III. Strack was inclined to suppose that the supposed coregency in Cyprus was a result of the settlement of 124, and for this reason favoured Cleopatra II.

Strack's arguments notwithstanding, the standard belief was that Neos Philopator was the younger son of Cleopatra II and Ptolemy VI who had, supposedly, briefly succeeded that king before being killed by Ptolemy VIII. The theory that a king briefly reigned between Ptolemy VI and Ptolemy VIII is of long standing, but it originally took a different form. Bouché-Leclercq, faced with the presence of Ptolemy Eupator and Ptolemy Neos Philopator in the dynastic cult between Ptolemy VI and Ptolemy VIII (his "Ptolemy VII"), understood them both to be ephemeral kings, and identified Eupator (his "Ptolemy VIII") with the son described by Justin (Histoire des Lagides II 56), and Neos Philopator (his "Ptolemy IX") with Memphites (Histoire des Lagides II 82 and n.1). When it became clear that Eupator had actually predeceased Ptolemy VI, the question of the identity of Neos Philopator was reopened.

L. Pareti, Atti della Reale Accademia delle Scienze di Torino 43 (1908) 509) argued that he was the youngest son in an anaylsis which became the conventional wisdom from 1908 till 1990. In that year, M. Chauveau (BIFAO 90 (1990) 135) pointed out that each point in Pareti's argument was open to question. The evidence is addressed point by point, with Pareti's analysis summarised in blue and Chauveau's objections summarised in black:

i) The literary sources. These are:

a) Justin 38.8, the primary source. This states that on Ptolemy VI's death the throne and the hand of Cleopatra II were offered to Ptolemy VIII by an embassy of a faction in Alexandria, and he succeeded without a struggle, even though Cleopatra and the nobility wanted Ptolemy VI's son to succeed. As soon as he entered Alexandria he put the partisans of the son to death, and killed the son himself on the wedding day, in his mother's arms.

The passage does not say that Ptolemy VI's son was declared king, and it insists that Ptolemy VIII succeeded without a struggle. Taken at face value this can only mean that Cleopatra II and Ptolemy VIII reached an accommodation concerning the rights of the son -- either the son was made coregent (for which there is no documentary support) or he was adopted by Ptolemy VIII and made heir. The account of Ptolemy VIII's purge is, in Chauveau's view, totally unmotivated, and the description of the murder of the son in his mother's arms is a rhetorical device which occurs elsewhere in Justin, e.g. the murder of the sons of Arsinoe II (Justin 24.3).

As will be seen below, new evidence shows that Chauveau was essentially correct: the son, while not (at least initially) adopted by Ptolemy VIII, was recognised as his heir.]

b) Orosius, Adversum Paganos 5.10 (a 6th century source believed to be derived from a lost book of Livy). This lists the sins of Ptolemy VIII: that he married his sister (i.e. Cleopatra II) and his step-daughter (i.e. Cleopatra III), and that he put to death his son by his sister (i.e. Ptolemy Memphites) and his brother's son. This list is placed between an account of the war against Aristonicus in Macedonia (131/0) and the war of Antiochus VII against the Parthians (130/29).

The only value of this passage is to reinforce the story of Justin that Ptolemy VIII, at some point, killed a son of Ptolemy VI.

c) Josephus, Contra Apionem 2.5. This states that Ptolemy VIII came from Cyrene on the death of Ptolemy VI and would have ejected Cleopatra II and "the sons of the king" if the Jewish general Onias had not intervened to help settle the civil war between them, which prevented the Alexandrians from being totally ruined. This account is intertwined with an account of how Ptolemy VIII attempted to massacre the Jews of Alexandria by elephants, but was prevented from doing so by his concubine Eirene or Ithaca.

This is a polemical account primarily aimed at proving the loyalty of the Jewish forces to Ptolemy VI and Cleopatra II against a usurping Ptolemy VIII, not historical narrative. It does not specify which king was the father of Cleopatra II's sons. It evidently confuses the accession of Ptolemy VIII, which does appear to have happened smoothly as Justin says, with the civil war between Ptolemy VIII and Cleopatra II over a decade later, which was clearly very destructive. Thus it has no value for proving the existence of a son of Ptolemy VI in 145.

Chauveau proposes to explain the background to these passages by identifying the "son of Ptolemy VI" killed by Ptolemy VIII with the pretender put forward by Galaistes at an uncertain date (Diodorus 33.20), whose fate is unknown but whom Ptolemy VIII had a clear interest in disposing of. Since later authors were interested in blackening Ptolemy VIII's name, the fact that this "son" was a pretender was played down. He suggests that the wedding story of Justin relates to the marriage of Cleopatra III, who is plausibly a candidate for the hand of the pretender; this would explain why Ptolemy VIII suffered no repercussions from his murder. He therefore dates the rebellion to the time of this wedding, c. 141/0.

ii) The son of Ptolemy VI most clearly documented by contemporary evidence, Ptolemy Eupator, had predeceased him, therefore the son discussed by Justin must be different.

While there is now contemporary documentary evidence for such a son, the evidence suggests that he was never treated as a coregent.

iii) The double date of year 36 = year 1, seen in coins, papyri and inscriptions, apparently provided decisive proof of a coregency.

However, O. Mørkholm (ANSMN 20 (1975) 7, 9 and pl II.4 and II.5) showed that use of the era of "year 36 = year 1" in coinage was suspended before the death of Ptolemy VI. Hence the double date can be more easily explained by reference to Ptolemy VI's accession as king of Syria.

iv) The epithet of Neos Philopator appeared in the list of deified kings at a position that requires a ruler who died after Ptolemy VI and before Ptolemy VIII.

But Ptolemy Memphites also fits the bill, because Ptolemy Neos Philopator only appears in the dynastic cult after 118, after the final settlement of the civil war of 132. The murder of Ptolemy Memphites was clearly a key event in that war. His incorporation in the dynastic cult would more reasonably be regarded as part of the settlment than the murder of an older half-brother which occurred 13-14 years earlier.

The only significant counter to this came from H. Heinen, Akten des 21. Internationalen Papyrologenkongresses I 449. This response addressed only the interpretations of the literary sources proposed by Chauveau, and insists that they show the existence of a son in 145, although Heinen conceded that the question of whether he was a coregent or successor of Ptolemy VI required further investigation.

The question appears to be settled with the publication of pKöln 8.350 by K. Maresch, and the subsequent analysis of M. Chauveau, RdE 51 (2000) 257. This papyrus, published in 1997, contained a highly fragmentary dating formula, dating it to 5 Mesore of year 20+[x]. From the list of gods in the dynastic cult, it must have dated from the reign of Ptolemy VIII. Since it clearly named only one queen Cleopatra it must date from either the period before his marriage to Cleopatra III in year 30 = 141/0, or after the rebellion of Cleopatra II in 132; the fragmentary date ensures the former. The canephore's name is lost, but she was the daughter of a Demetrios. pHeid inv. G 4868, unpublished, is dated to year 26. It names the athlophore as Heliod[or]a daughter of Demetrios. Another unpublished papyrus, pDublin ined., dated to year 27, names the canephore of that year as Heliodora. Clearly Bell's law, in which the athlophore of one year typically became the canephore of the next, applies, and so pKöln 8.350 may be securely dated to 5 Mesore year 27 of Ptolemy VIII = 28 August 143. The eponymous priest is named as Ptolemy [son of king Ptolemy.... and queen] Cleopatra Euergetes = Cleopatra II. Since she is named as the beneficient goddess, rather than one of the beneficient gods, the father of the priest cannot have been Ptolemy VIII, and must therefore be Ptolemy VI. Thus pKöln 8.350 confirmed the existence of the younger son, but also shows him being treated as the heir to Ptolemy VIII. In other words, he was not made king or coregent, and he was not murdered as Justin says, or at least not at the time of the marriage of Ptolemy VIII to Cleopatra II.

Chauveau's case for supposing there was no son at all living at the time of Ptolemy VI's death is now disproved. The other significant point where I feel Chauveau is likely to be wrong, and Heinen right, is the timing of Galaistes' revolt. I think that this event is more plausibly dated to the accession of Ptolemy VIII than to the marriage of Cleopatra III. Galaistes had been in charge of significant forces during Ptolemy VI's campaign in Syria (Diodorus 33.20), and his estates in Egypt were confiscated in the early weeks of Ptolemy VIII's reign (pKöln V 222-225 -- see L. Criscuolo, ZPE 64 (1986) 83). These two events explain his motivation and his capability to rebel.

If Neos Philopator was not the immediate successor of Ptolemy VI, it remains to identify him. As Strack noted long ago, from his place in the cult sequence between Eupator and Euergetes, Neos Philopator died after Ptolemy VI and after Ptolemy Eupator. Strack's proposal that he was a younger brother of Memphites is based entirely on the Cypriote coinage apparently dated year 50=1, but this interpretation is almost certainly incorrect. We are left, then, with two candidates: the younger son of Ptolemy VI, now not as his successor but as first heir to Ptolemy VIII; and Ptolemy Memphites.

As noted above, M. Chauveau, BIFAO 90 (1990) 135, argued in favour of Memphites on circumstantial grounds: that his appearance in the cult approximately coincides with the final decree of amnesty in 118, and can be explained, in essence, as an act of atonement and reconcilation by his father and murderer. M. Chauveau, RdE 51 (2000) 257, 259f has recently pointed out some positive evidence supporting the same conclusion. He notes two inscriptions on either side of a door in the temple of Khonsu at Karnak, which both give the complete titulary of Ptolemy IX and Cleopatra III. This dates the inscriptions between 115 and 107, i.e. within a decade of the incorporation of Ptolemy Neos Philopator into the dynastic cult. Each inscription gives a different enumeration of the dynastic ancestors. On the left we have the Theoi Adelphoi and Euergetai, followed by Neos Philopator, Euergetes II (i.e. Ptolemy VIII) and a Thea Philometora, who can only be Cleopatra II. On the right side we have the Theoi Philopatores and Epiphanes followed by Eupator and Philometor. Chauveau argues that the final groups represent family groupings, i.e. Eupator as a son of Ptolemy VI and Neos Philopator as a son of Ptolemy VIII and Cleopatra II. On this basis, Ptolemy Neos Philopator can only be Ptolemy Memphites. Ý

[10] P. W. Pestman, Chronologie Égyptienne d'après les textes démotiques 146(1): Not present in pdem. Rylands 17, 19 dated Mecheir year 52 = c. March 118; present in pdemBerlin 3101 dated Pharmouthi year 52 = c. May 118. Ý

Update Notes:

10 Feb 2002: Added individual trees

22 Feb 2002: Split into separate entry

20 April 2003: Refined death date; reviewed Green's suggestion that he was proclaimed coregent in absentia by Cleopatra II in 130 (thanks to Ian Mladjov).

23 Aug 2003: Added Xrefs to online Justin

19 Oct 2003: Changed Xrefs for online Periochae to Lenderer translation.

13 Jan 2005: Consolidated Neos Philopator-related issues under Memphites and added discussion of Strack's views.

1 Feb 2005: Adjust in light of Huss' argument that this Ptolemy is not the "eldest son" of Ptolemy VIII summoned from Cyrene to Cyprus and murdered there.

11 Mar 2005: Added Greek transcription

27 Oct 2005: Add Memphites as eponymous priest in year 36 in light of pdem Tebt 5944 (C. di Cerbo, Fs Zauzich, 116)

16 Sep 2006: Add Xref to Packhard Humanties DBWebsite contents © Chris Bennett, 2001-2011 -- All rights reserved