Ptolemy V

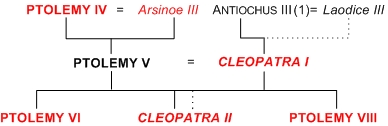

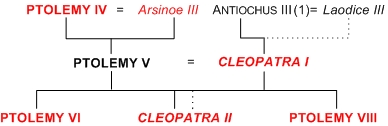

Ptolemy V Epiphanes Eucharistos1 king of Egypt, son of Ptolemy IV by Arsinoe III2, born late year 12 or early year 13 of Ptolemy IV = 2103, official birthday 30 Mesore4, associated on the throne with his father 30 Mesore year 12 = 9 October 210 or 17 Phaophi year 13 = 30 November 2105, succeeded him summer 204 before 1 Mesore = 8 September 2046, ruler under the regency of Sosibius7 and Agathocles till October 2038, then of Tlepolemus till 202 or 2019, then of Aristomenes till his majority was declared in c. Oct/Nov 19710, was incorporated in the dynastic cult with Cleopatra I probably in 194/3 as the Manifest Gods, Qeoi EpifaneV11, recaptured rule of Upper Egypt from Ankhwennefer between Epeiph year 14 = 6 August - 4 September 191 and Mesore year 15 = 5 September - 4 October 19012, victor in the Panathenaian Games of 18212.1, died Mesore year 25 (Eg.) = September 18013, rumoured to have been poisoned14, and was succeeded by Cleopatra I and Ptolemy VI with no intervening coregency15.

Ptolemy V's titles as king of Egypt were:16

Horus Hwnw xaj-m-nsw-Hr-st-jt.f17

Two Ladies wr-pHtj smn-tAwj snfr-TAmrj mnx-jb-xr-nTrw18

Golden Horus wAD-anx-n-Hnmmt nb-HAbw-sd-mj-PtH-TATnn jty-mj-Ra19

Throne Name jwa-n-nTrwj-mr(wj)-jt stp-(n)-PtH wsr-kA-Ra sxm-anx-n-Jmn20

Son of Re ptwlmjs anx-Dt mrj-PtH21Ptolemy V had one marriage, to Cleopatra I, daughter of Antiochus III of Syria22, by whom he had Ptolemy VI23, Ptolemy VIII24 and presumably Cleopatra II25. Additionally, there were marriage negotiations for him between the Egyptian and Macedonian courts on his accession; the identity of the Macedonian princess involved is unknown26.

[1] PP VI 14546. Gr: PtolemaioV EpipfanhV EucaristoV. Usually known only by the first epithet, Epiphanes ("manifest"). The title first appears in Tybi year 7 = February/March 198 (pReceuil 8 = pdem Dublin 1659 = pdem Hincks 2). C. G. Johnson, Historia 51 (2002) 112, notes that OGIS 98, an altar dedication by Ptolemy V, Cleopatra I and their son Ptolemy (VI), names the parents as the Qeoi EpifaneiV, the first recorded use of divine epithets by a living monarch.

R. A. Hazzard, HThR 88 (1995) 415 notes the occasional appearances of two comets or stars on some coins of Ptolemy V (J. N. Svoronos, Die Münzen der Ptolemäer Nos 1249 (pl. 41a.4,5), 1254 (pl. 41b.15), 1257 (pl. 41b.17,18); D. Kiang, ANSMN 10 (1962) 69) which he dates to the period 204 to 198 (years 1 to 7). He correlates these with the comets observed in Babylonia between June 24 and July 22 210 = c. 10-12 Duzu 102 SE (D. K. Yeomans, Comets: A Chronological History of Observations 364, citing a letter dated 13 November 1989 from H. Hunger to F. R. Stephenson on unpublished fragments of Babylonian diaries related to comets in the British Museum; cf now BM 45608+45717 in A. Sachs & H. Hunger, Astronomical Diaries and Related Texts from Babylonia II 185) and in China the seventh month of year 3 of Han Kao Ti = 14 August - 11 September 204 (Pan Ku, Ch'ien Han Shu 27/3, 3/26b, cited in H. P. Yoke, Vistas in Astronomy 5 (1962) 128, 143 no. 23). Hazzard suggests that the epithet refers to these comets appearing around the times of his birth and his accession respectively. Ý

[2] Justin 30.2 (calling her "Eurydice"). There is a remote possibility that his true biological mother was Agathoclea. Ý

[3] Year of birth inferred from Justin 30.2 which states that he was five years old when his father died. This works comfortably with the presumed birthdate of 30 Mesore year 12. Jerome, Commentary on Daniel 11.13-14, states that he was four. This is extremely unlikely. The earliest reference to him is pGurob 12 dated 25 Pharmouthi year 13 of Ptolemy IV = 5 June 209, i.e. he was born in or before the beginning of June 209, but his accession took place in late summer 204. Ý

[4] Rosetta Stone (BM EA 24 = OGIS 90, trans. M. M. Austin The Hellenistic World from Alexander to the Roman Conquest 374 (227)). This is generally regarded as his actual birthday, but L. Koenen, Eine agonistiche Inschrift aus Ägypten und frühptolemäische Königsfeste 73, who argues that the birthdates of Ptolemy II and Ptolemy III are official festivals, not natural birthdates, notes that 30 Mesore corresponds to a major Egyptian feast, and so may well represent the date (soon after birth) when he was made a coregent. Ý

[5] See discussion under Ptolemy IV. Ý

[6] See discussion under Ptolemy IV. Ý

[7] After the account of Ptolemy V's accession (Polybius 15.25.4) Sosibius disappears from Polybius, and it is generally supposed that he died at about this time. Sosibius, son of Dioscurides (who is otherwise unknown), rose to power under Ptolemy III, and was head of government for most if not all the reign of Ptolemy IV (Polybius 5.35.7, 5.63). He was eponymous priest in year 13 of Ptolemy III = 235/4 (PP III 5272 -- pPetrie I 18(I)). His daughter Arsinoe (PP III 5027) was canephore in year 8 of Ptolemy IV = 215/214 (BGU 6.1264). His son Sosibius was a member of the royal guard and instrumental in the overthrow of Agathocles (Polybius 15.32.6). A second son Ptolemy was sent as an ambassador to Philip V of Macedon in 204/3 (Polybius 15.25.13). While nothing is known of his more distant ancestry, it seems to me possible that he was grandson of Sosibius of Tarentum, captain of the guard under Ptolemy I or Ptolemy II (Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, 12.2.2. Josephus names Ptolemy II, but also mentions Demetrius of Phaleron in connection with the same events. Demetrius was imprisoned by Ptolemy II (Diogenes Laertes 5.78), probably very shortly after the start of his reign as a partisan of Ptolemy Ceraunus (see R. A. Hazzard, Phoenix 41 (1987) 140, 149 and n. 31)). Ý

[8] See discussion under Agathoclea. Ý

[9] Tlepolemus (PP I 50), strategos of Pelusium, was selected as regent after the fall of Agathocles (Polybius 16.21), though initially Sosibius son of Sosibius had control of the royal seal. The date of his fall is inferred to have occurred at this time because Aristomenes is found heading the government after about 200. His mother-in-law Danae had been abused by partisans of Agathocles at the start of the riots which led to his fall (Polybius 15.27.2). He was probably grandson of Tlepolemus son of Artapates, victor in the horse race at the 131st Olympics in 256 (Pausanias 5.8.11), eponymous priest at the end of the reign of Ptolemy II and the start of that of Ptolemy III, commander of the Ptolemaic forces in Caria in the Third Syrian War, and mentioned in several inscriptions in Lycia. Tlepolemus himself may be identified with the Tlepolemus son of Artapates named as a priest at Xanthos in Lycia in a Seleucid inscription dated Hyperberetaios year 117 SE = September/October 196 (J. & L. Robert, Fouilles d'Amyzon en Carie I (1983) 15B (p154ff); 168ff.). He may be identified with or related to the Tlepolemus who acted as an ambassador for Ptolemy VI to Antiochus IV in 169 (Polybius 28.19.6). F. W. Walbank (Commentary on Polybius II 487) identifies two other individuals as possible members of this family: Artapates son of Stasithemios honoured at Xanthus and an Artapates known as a general from "late" inscriptions at Silsilis in Cilicia. Ý

[10] Aristomenes (PP I 19) was an Arcanian, with a daughter called Agathoclea (Polybius 15.31.7). His father was Mennaus; he was eponymous priest in year 2 of Ptolemy V = 204/3 (PP III 5020; pdem Leiden I 373b, c). The coming of age (anaklhthria) of Ptolemy V is described in Polybius 18.55, covering events of Ol. 145,4 = summer 197 - summer 196. F. W. Walbank (Commentary on Polybius II 623f.) argues that the events of 17 Phaophi referred to in the Rosetta Stone (BM EA 24 = OGIS 90, trans. M. M. Austin The Hellenistic World from Alexander to the Roman Conquest 374 (227)) describe an Egyptian coronation, which should therefore be dated to 17 Phaophi year 8 = 26 November 197, that this must be distinguished from the anaklhthria, a Greek ceremony, and that the latter must therefore have been held shortly before. Ý

[11] P. W. Pestman, Chronologie égyptienne d'après les textes démotiques (332 av. J.-C. - 453 ap. J.-C.) 137, notes that the title appears for eponymous priests in Greek papyri starting with year 12 = 194/3, which is the year Ptolemy V married Cleopatra I. However, it does not appear in demotic papyri till year 19 = 187/6. Notwithstanding Pestman's statement, W. Clarysse & G. van der Veken, The Eponymous Priests of Ptolemaic Egypt, note that the priest for year 12 is unknown, as is that for years 16 = 190/89 and 17 = 189/8. pTebt. 3.2.975, naming <lost> son of Nikanor, belongs to one of these years. pdem Cairo 2.31015, naming Pwl[...] as eponymous priest and AytA[...] as athlophore must also cover one of these years. It probably covers year 16, since in this period the athlophore usually becomes canephore in the following year, and the canephores for years 13 and 18 are known to be Apollonia daughter of Athenodoros and Galatia daughter of Praxitimos respectively. Thus the earliest certain attestation of the title is for 24 Mecheir year 13 = 1 April 192, for which see pTebt. 3.1.816. W. Clarysse (pers. comm.) notes that if Xandikos (Mac.) can correctly be equated with Phaophi (Eg.), then BGU 10.1967 is earlier, datable to Nov. 193. (The surviving traces of the year match 13, 15 or 19; 13 is inferred from the mention of the Feoi SothreV, which was suspended after year 13 for unknown reasons -- see E. Lanciers, ZPE 66 (1986) 61). Ý

[12] See discussion under Ankhwennefer. Ý

[12.1] IG II2 2314 line 41. The identity of the king Ptolemy son of king Ptolemy named here is dependent on the date, which is discussed in S. V. Tracy & C. Habicht, Hesperia 60 (1991) 187 at 219ff. It principally depends on the physical relationship of this inscription to the new list published in that article, which comes from the same stone. Ý

[13] The Canon of Claudius Ptolemy gives Ptolemy V 24 years, hence Ptolemy VI's reign officially began in year 25 = 7 Oct. 181 - 6 Oct. 180 under the Egyptian calendar. The last known date is a retrospective reference to Mesore year 25 in pColl. Youtie 1.12 = 2 Sept. 180 - 1 Oct. 180, suggesting he died in September or very early October.

Porphyry in Eusebius, Chronicorum I (ed. Schoene) 161, gives 23 years (as XXIII), but the Greek version gives 24 (written as words). It is usually accepted that the correct number is 24 and the Latin (i.e. Armenian) version amended accordingly. However, R. A. Hazzard, Fs. Le Rider, 147 at 151, accepts 23 years as the correct version, and concludes that Porphyry was using a source based on Macedonian regnal years and that the datum indicates that Porphyry considered that the reign of Ptolemy VI was accounted as beginning in the 24th Macedonian regnal year of Ptolemy V. He does not present any justification for the choice, and does not recognise the discrepancy in the two versions of Eusebius; moreover the inference he draws is very questionable, though not impossible. See further discussion below.

The datum is an important test for determining the basis of Porphyry's chronology. By dead reckoning, year 24 of Ptolemy V = Ol. 149.3 = 182/1 according to Porphyry. If, as is generally assumed, we suppose he is using a postdated regnal dating system aligned to Olympic years, then this the year of Ptolemy V's death. However, if we suppose he is using an antedated regnal dating system of Egyptian years aligned to Olympic years, then Ptolemy V died in the following year, Ol. 149.4 = 181/0, which matches the Canon and the Egyptian data. Either way, a reign of 23 years cannot be aligned with the Egyptian data. Hence the chronology of the death of Ptolemy V shows that Porphyry was relying on source data that antedated Ptolemaic reigns. Ý

[14] Jerome, Commentary on Daniel 11.20. Although the text of the latter actually says that "Seleucus" was poisoned by his own generals, it is obvious from the context that Ptolemy V is meant since Jerome has just stated that he is explaining how Porphyry believes that Daniel 11.20 does not refer to the destruction of Seleucus II but to the destruction of Ptolemy V. Ý

[15] Ptolemy VI Philometor is named as his successor in the canon of Claudius Ptolemy. pRyland IV.589, dated to year 2, names queen Cleopatra (I) ahead of king Ptolemy (VI) son of the divine (Ptolemy V) Epiphanes.

R. A. Hazzard (Fs. Le Rider, 147) argues that Ptolemy V associated Ptolemy VI on the throne shortly before 23 July 181. His arguments are as follows:

1) Certain dual dates in the reigns of Ptolemy V and VI demonstrate that the Macedonian lunar calendar was still in use in Alexandria during their reigns. These documents are: the Rosetta Stone (BM EA 24 = OGIS 90), equating 4 Xandikos (Mac.) with 18 Mecheir (Eg.) in year 9 of Ptolemy V; UPZ 1.111, a letter from Ptolemy VI equating 4 Peritios (Mac.) with 25 Mesore (Eg.) in his year 18 = 22 September 163; and UPZ 1.113, a circular from the dioiketes in Alexandria in year 26 of Ptolemy VI equating 1 Xandikos (Mac.) with 25 Thoth (Eg.) = 25 October 156.

2) J. N. Svoronos, Die Münzen der Ptolemäer No. 1486 (pl. 48.19,20), interprets a mark on a silver tetradrachm minted at Ake-Ptolemais in Phoenicia, as a date: "Egyptian year 33". If this is an Egyptian civil year then the coin was minted between 29 September 149 and 28th September 148; but Ptolemy's Syrian expedition in support of Alexander Balas was in year 165 Seleucid (I Maccabees 10.67) which started on 23 September 148. He concludes that this coin, and other coins of Ptolemy VI, are dated according to his Macedonian years, which he supposes followed the Macedonian calendar as it had been under Ptolemy II.

Year 1 Macedonian should then be a full year, based on the date of the accession of Ptolemy VI. But, although we have a coins of each of Ptolemy V in year 24 and of Ptolemy VI starting in year 2, we have no coins of year 1 of Ptolemy VI. Further, we possess Cypriote coins minted at Salamis which demonstrably used the same obverse die in year 24 of Ptolemy V (Mac.) and year 2 of Ptolemy VI (Mac.) (O. Morkhølm & A. Kromann, Chiron 14 (1984) 149 at 156 nos 16-19 (Svoronos 1348 and 1324 (plates 45.23 and 45.2) -- Svoronos had attributed the year 2 coinage to Ptolemy V). Hazzard concludes that year 1 (Mac.) of Ptolemy VI was the same as or largely overlapped year 24 (Mac.) of Ptolemy V, i.e. that there was a nominal coregency.

3) In further support he notes that Porphyry gives Ptolemy V 23 years while the Canon of Ptolemy gives him 24. He holds that this shows that Ptolemy V did not complete his 24th Macedonian year. This is explicable if the reign of Ptolemy VI was accounted from the beginning of a coregency that began in year 24 (Mac.) of Ptolemy V. He cites the coregency-based dating of Ptolemy II as a precedent, and notes that several other coregencies are known, including a nominal coregency of Ptolemy IV and Ptolemy V.

Based on this model, Hazzard estimates the start of Ptolemy VI's Macedonian reign as follows. The Macedonian year was 354 or 384 days long = 369 +/- 15 days on average. UPZ 1.111, dated 22 September 163, was therefore written about 369x17+x = 6273+x days into the reign, i.e. Ptolemy VI acceded as coregent before 20 July 180. UPZ 1.113, dated 25 October 156, was written 369x25+y = 9225+y days into the reign, i.e. Ptolemy VI acceded as coregent before 23 July 181. His year 34, then could have started as late as 369x33 = 12177 days later, i.e. as late as 24 November 148, allowing for just over two months overlap between year 33 (Mac.) and year 165 SE and implying that Svoronos 1486 was struck in those two months.

This analysis is questionable on many grounds.

First, while UPZ 1.111 and 1.113 certainly show the continuance of some form of the Macedonian calendar, the very data that Hazzard uses shows that it was not still regulated as it had been under Ptolemy II.

From UPZ 1.111, dated 4 Peritios year 18 = 22 September 163, we have 1 Peritios year 18 = 19 September 163. From UPZ 1.113, 1 Xandikos year 25 = 25 Thoth year 26 = 25 October 156. The difference is 2609 days = 31x29 + 57x30, i.e. there are 88 lunar months between 1 Peritios year 18 and 1 Xandikos year 26, which is 7 Macedonian years + 4 months, for a phase shift of 2 months. Clearly there were only two embolimos months in that time. But on Hazzard's model there ought to be 3 or 4.

We can confirm this result by looking more closely at the Rosetta stone. As Hazzard says, this gives the synchronism 4 Xandikos = 18 Mecheir year 9 of Ptolemy V, but there are good reasons for supposing this is an error. First, it is well out of alignment with the Macedonian calendar as it existed under Ptolemy IV. Second, the decree itself gives two different accession dates for Ptolemy V: 17 Phaophi (II Akhet 17) in the hieroglyphic text, and 17 Mecheir (II Peret 17) in the demotic text. The same seasonal confusion between Akhet and Peret suggests that the date of the decree should be emended to 4 Xandikos = 18 Phaophi, which would bring it closer to the alignment under Ptolemy IV. This conjecture is now confirmed through SB 20.14659 = C. Ptol. Sklav. I 9 (L. Koenen in Atti del XVII Congresso internazionale di papirologia III 915), which contains a clear double date from the previous year: 26 Hathyr = 4 Daisios year 8. It also gives us that 15 Xandikos is on or after 2 Phaophi of that year. From this it is clear that the Rosetta equation should in fact be 4 Xandikos = 18 Phaophi. The period from 1 Xandikos=15 Phaophi year 9 of Ptolemy V = 24 November 197 BC to the 1 Xandikos after 4 Peritios=25 Mesore year 18 of Ptolemy VI = 18 November 163 BC is 34 Egyptian years + 2 days. This must correspond to 34 Macedonian cycles, i.e. in this time the Macedonian year has exhibited a net gain of only 2 days against the Egyptian year. That is, it seems clear that under Ptolemy V and Ptolemy VI, the Macedonian calendar was aligned with the Egyptian calendar and no longer operated on a cycle of intercalations in alternate years.

Thus Hazzard's argument is based on a false assumption about the operation of the Macedonian calendar in this period.

Turning to the regnal years, the evidence of Porphyry is of no value, since there are good grounds to emend it to 24 years. Moreover, even supposing that Ptolemy VI used a Macedonian year, there is no reason to suppose that his first Macedonian year was of regular length. For both Ptolemy III and Ptolemy IV, the evidence shows that their first year was short, lasting from the date of accession to the following Dystros.

Turning to Svoronos 1486, the formula on this coin is not given as LLG (year 33), as one would expect. Instead it is written as the mirror image of A-GLG, i.e. there is no year sign (L), but two reversed gammas, one of which must be understood to represent an inversion of the year sign. In addition, there is an unexplained A. Svoronos interpreted this as a date, year 33, with the A indicating that the date was according to the Egyptian calendar (A[IGYPTOS]). Hazzard's analysis shows that this cannot be correct, but he has not proven that the formula on the coin should be interpreted as a date at all. Since the only other coinage which Svoronos attributes to Ptolemy VI from Ptolemais (nos. 1487 and 1488, pl. 48.21-23) do not include comparable formulae, we have no comparative material; in any case, Svoronos' attribution of these coins is doubtful (C. Lorber, pers. comm. 11/11/07). Until it can be shown that Svoronos 1486 is actually dated, there is no reason to consider it as evidence.

Turning to the evidence of a numismatic transition from year 24 of Ptolemy V to year 2 of Ptolemy VI, it is necessary to explain the absence of coinage for both year 25 of Ptolemy V and year 1 of Ptolemy VI.

Considering first the case of year 1 of Ptolemy VI: Hazzard's model certainly predicts very little if any coinage for year 1 (Mac.) of Ptolemy VI since it mostly overlapped with year 24 (Mac.) of Ptolemy V. However, the same would be true if Ptolemy VI's Macedonian regnal years were aligned with his Egyptian regnal years in this period, since his first Egyptian regnal year was very short.

The complementary question arises at the other end of the reign -- year 36. The earliest Egyptian date for Ptolemy VIII to date is 11 Epeiph year 25 = 4 August 145. Ptolemy VI died perhaps a month earlier, which is after the bulk of the Egyptian year. On Hazzard's model, the latest date for the start of year 36 (Mac.) is 369x35 days after 23 July 181 = 2 December 146. Therefore, both models also predict nearly a normal years production for Ptolemy VI year 36. O. Mørkholm, ANSMN 20 (1975) 7, 9, noted that we can distinguish no less than 5 obverse dies for this year. Hence the numismatic data on production is consistent with both models.

We are left with the absence of coins for year 25 of Ptolemy V and the use of the same obverse die in two different ciities in years 24 of Ptolemy V and 2 of Ptolemy VI. While the mere absence of coins could (and probably is) simply be due to failure to discover any, the second point, at first sight, certainly appears to imply that year 25 was short, or non-existent. Nor can the argument be entirely dismissed on calendrical grounds. Since we have Egyptian dates as late as Mesore year 25, and since Ptolemy V appears to have succeeded late in Egyptian year 1, the elapsed time of his reign was about 24 full years. Thus, an anniversary-based regnal year of some type could, in theory, explain this gap in the coinage. Nevertheless, on this system his Egyptian regnal year was almost a year in advance of the anniversary-based year, so we should expect to see documents with double year dates. To my knowledge, while dual dated documents certainly exist, none of them have double year dates, and the regnal year 9 of the Rosetta Stone (OGIS 90), which ought to be that of the Alexandrian court, certainly equals the Egyptian civil year 9. Thus, if such a system was used, it almost certainly did not apply to the Egyptian chora. It might still be argued that the traditional regnal dating was only used in external territories such as Cyprus. On this conjecture, the coinage would arguably be evidence that the system of regnal dating changed in the provinces on the death of Ptolemy V, but it would not be evidence of a coregency.

However, a closer consideration of the data presented in O. Morkhølm & A. Kromann, Chiron 14 (1984) 149 suggests a simple alternate explanation: that the volume of coin production in year 25 was so low that the same obverse dies lasted into a third year in both Paphos and Salamis. They note (p153) that the total production of dated coinage for the 29 years covered by the paper, from year 14 of Ptolemy V = 192/1 to year 18 Ptolemy VI = 164/3, over 3 mints, used only 61 dies. Moreover they give one other example of a Salamanian obverse die being used into a third year: Svoronos 1339 and 1340 (plate 45.15,16), dated to years 15 and 17 of Ptolemy V. In this case, no other explanation is possible, and it shows that continuing low production volumes in years 24 Ptolemy V - year 2 Ptolemy VI is sufficient to explain the reuse of the obverse dies in those years.

Thus, Hazzard's case for a coregency is without any foundation. Ý

[16] Transliterations follow J. von Beckerath, Handbuch der ägyptischen Königsnamen (2nd edition) 236 (5). All titles are given on CCG 22188, a more complete version of the hieroglyphic section of the Rosetta Stone (BM EA 24 = OGIS 90, demotic trans. R. S. Simpson in R. Parkinson et al. Cracking Codes: the Rosetta Stone and Decipherment 198) = H. Gauthier, Livre des Rois d'Égypte IV 282 XXVI. The assignment to Ptolemy V is guaranteed from the throne name. Ý

[17] "The youth who has appeared as king in place of his father". For the reasoning associating this name with Ptolemy V, see discussion above. Ý

[18] "Whose might is great, who has established Egypt, causing it to prosper, whose heart is beneficial before the gods". For the reasoning associating this name with Ptolemy V, see discussion above. Ý

[19] "Who has caused the life of the people to prosper, Lord of the years of Jubilee like Ptah-Tennen, King like Re". For the reasoning associating this name with Ptolemy V, see discussion above. Ý

[20] "The son of the Father-Loving Gods, whom Ptah has chosen, to whom Re has given victory, the living image of Amun". For the reasoning associating this name with Ptolemy V, see discussion above. Ý

[21] "Ptolemy, living forever, beloved of Ptah". For the reasoning associating this name with Ptolemy V, see discussion above. Ý

[22] Livy 35.13. Ý

[23] Polybius 28.20.9. Ý

[24] Jerome, Commentary on Daniel 11.27-30. Ý

[25] See discussion under Cleopatra II. Ý

[26] Polybius 15.25.13. On his accession, Ptolemy, son of Sosibius, was sent to Philip V "to arrange for the proposed match". Ý

Update Notes:

10 Feb 2002: Added individual trees

21 Feb 2002: Split into separate entry

19 May 2002: Corrected Egyptian date equations as necessary

9 April 2003: Noted that Ptolemy V was the first king to take a divine epithet in his lifetime.

18 May 2003: Added Xrefs to the Lacus Curtius edition of Polybius; added published ref to the Babylonian sighting of the comet of 210

23 Aug 2003: Added Xrefs to online Justin

24 Feb 2004: Added Xrefs to online Commentary on Daniel

20 Nov 2004: Extended discussion of Hazzard coregency hypothesis

16 Dec 2004: Added notice of his Panathenaian victory

11 Mar 2005: Added Greek transcription

6 Oct 2005: Adjust discussion of Hazzard proposal to correct Rosetta date to 18 Phaophi based on SB 20.14659 and to correct and simply the argument

3 Dec 2005: Adjust discussion on Porphyry.

14 Sep 2006: Add links to Packard Humanities DB, Canon at Attalus

11 Nov 2007: Incorporate Morkholm/Kromann data into discussion of Hazzard's coregency theory -- thanks to Catharine Lorber for making me realise the omission

27 Nov 2010: Fix broken DDbDP linksWebsite © Chris Bennett, 2001-2012 -- All rights reserved.