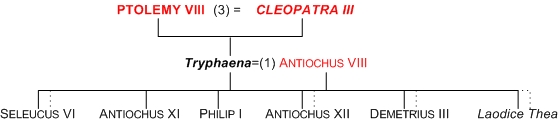

Tryphaena1, daughter of Ptolemy VIII2 and Cleopatra III3, born probably in 141 or early 1404, married as his first wife Antiochus VIII Grypus, king of Syria5, in 1246, by whom she was presumably the mother of Seleucus VI7, certainly the mother of Antiochus XI8 and Philip I9, presumably the mother of Demetrius III10, Antiochus XII11 and Laodice Thea, wife of Mithridates I of Commagene12, by whom she had further traceable descendants13; was captured and executed by Antiochus IX Cyzicenus14 c. 112/1 or 110/915.

[1] PP VI 14521. Gr: Tryfaina. Usually called Cleopatra Tryphaena in modern sources, although there is no ancient justification for this. Ý

[2] Justin 39.2. Ý

[3] Justin 39.3, where Tryphaena accuses Cleopatra IV of marrying outside Egypt against their mother's wishes. Ý

[4] Constraints between 141 and 139 inferred from the date of her marriage and from the likely birth of Cleopatra III's oldest son, Ptolemy IX, in 142, on the assumption that he was her first child. If the birth of Ptolemy X is correctly estimated to be in year 31 = 140/39, then Tryphaena was most likely born in 141. Ý

[5] Justin 39.2 Ý

[6] Justin 39.2 synchronises this with the restoration of Cleopatra II into the Egyptian ruling trio, which contemporary records indicate took place in 124. Ý

[7] Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, 13.13.4; Porphyry in Eusebius, Chronicorum I (ed. Schoene) 259. His mother is not explicitly named but is generally and reasonably assumed to be Tryphaena. He killed Antiochus IX. His dates of reign are uncertain. They are most recently estimated, in O. D. Hoover, Historia 56 (2007), 280 at 300, at 96/5 to 94/3. Ý

[8] Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, 13.13.4; Porphyry in Eusebius, Chronicorum I (ed. Schoene) 261. Porphyry names Antiochus XI as twin brother of Philip I, who is specifically called a son of Tryphaena. His dates of reign are uncertain. They are most recently estimated, in O. D. Hoover, Historia 56 (2007), 280 at 301, at c. 93. Ý

[9] Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, 13.13.4; Porphyry in Eusebius, Chronicorum I (ed. Schoene) 261. Porphyry gives the maternity. His dates of reign are uncertain. They are most recently estimated, in O. D. Hoover, Historia 56 (2007), 280 at 301, at 88/7-c. 75. He had a son by an unknown woman, Philip II, who was also briefly a Seleucid king (Diodorus 40.1a, 1b) and a candidate for the hand of Berenice IV. Ý

[10] Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, 13.13.4, 13.14.3. His mother is not explicitly named. It is possible that Antiochus VIII had a second wife in the near-decade between the death of Tryphaena and his marriage to Cleopatra Selene but there is no evidence for it. That being the case, it is generally and reasonably assumed that his mother was Tryphaena. He was made king of Damascus by Ptolemy IX, but was captured by Mithridates II king of Parthia and held prisoner in Parthia for the rest of his life. His dates of reign are uncertain. They are most recently estimated, in O. D. Hoover, Historia 56 (2007), 280 at 301, at 97/6-88/7 in Damascus, with a brief rule in Antioch in 88/7. Ý

[11] Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, 13.15.1. His mother is not explicitly named. It is possible that Antiochus VIII had a second wife in the near-decade between the death of Tryphaena and his marriage to Cleopatra Selene but there is no evidence for it. That being the case, it is generally and reasonably assumed that his mother was Tryphaena. His dates of reign are uncertain. They are most recently estimated, in O. D. Hoover, Historia 56 (2007), 280 at 301, at 88/7-84/3 in Damascus. Ý

[12] IGLSyr 1.1; see discussion by R. D. Sullivan in H. Temporini, W. Haase (eds.) Aufstieg und Niedergang der Römischen Welt II.8 753ff. Her father is named in IGLSyr 1.1 and some other inscriptions as Antiochus VIII, but her mother is not explicitly named anywhere, so far as I can determine. His mother is not explicitly named. It is possible that Antiochus VIII had a second wife in the near-decade between the death of Tryphaena and his marriage to Cleopatra Selene but there is no evidence for it. That being the case, it is generally and reasonably assumed that her mother was Tryphaena. Ý

[13] Descendants of this marriage can be traced with high probability for 8 generations, well into the 2nd century AD -- see R. D. Sullivan in H. Temporini, W. Haase (eds.) Aufstieg und Niedergang der Römischen Welt II.8 stemma between 742 and 743, repeated in R. D. Sullivan, Near Eastern Royalty and Rome 100-30 BC Stemma 5.

Longer descents have been argued by C. Settipani, Nos ancêtres de l'antiquité 84ff., on the basis of Strabo 11.13.1. This passage states that: "Having been proclaimed king, Atropates organised Media as an independent state, and the dynasty descended from him maintains itself there in our own times, his successors having contracted marriages with the kings of the Armenians and Syrians, and, in later times, with the kings of the Parthians." Some aspects of these arguments were elaborated in a note posted to the UseNet group soc.genealogy.medieval in three parts (I, II and III) in August 1998. Settipani notes that Strabo is apparently listing the marriages in chronological order. Further, he is crediting the marriages with being a major factor in the survival and perpetuation of the dynasty, which in Settipani's view makes it very likely that they represent the marriages of Atropatenian kings to the daughters of the other kings named (i.e. that the last phrase should be understood as: "with the royal families of Armenia, Syria and, more recently, Parthia"). Further, the marriages resulted in some long-lasting benefit that was visible down to Strabo's time, the most likely of which, in Settipani's view is the descent of the kings from these marriages.

Two of these marriages can be identified from other sources. The Armenian marriage is that of Mithridates of Media with the daughter of Tigranes II of Armenia in or before 67 (Dio Cassius 36.14). The Median king Artavasdes son of Ariobarzanes, contemporary with Cleopatra VII and Antony, bears a typical Armenian royal name and was therefore, in all likelihood, a descedant of this marriage. Since Tigranes II became king in 95, the earliest date for the Armenian marriage is the late 90s. The Parthian marriage is connected with the ancestry of Artabanus III of Parthia, who we know was an Arsacid only on his mother's side (Tacitus, Annals 6.42). Before his accession in 11, Artabanus had been king of Media (Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 18.2.4), as was Vonones II in 51 (Tacitus, Annals 12.14). [Vonones was probably the brother of Artabanus since his son Vologeses I is said by Josephus (Antiquities of the Jews 20.3.4) to be the "brother" of Gotarzes II, who we know from a coin calling him "Arsaces, king of kings, called Gotarzes, son of Artabanos" was in fact the son of Artabanus III.] Since Strabo wrote between about 18/9 and 23 AD, it follows that Artabanus and Vonones were from the Atropatenian dynasty on their father's side. The marriage between their parents must have happened c. 15-10 BC. Both these marriages have the characteristics that are expected from Strabo's words.

The third, "Syrian", marriage must have occurred between these two. If the marriage was also to a Median king, and was also ancestral to later Median kings, then it should have occurred between the generation following the Armenian marriage and the generation preceding the Parthian one, i.e. between about c. 75 and about 30. Now, Strabo 16.2.2 defines "Syria" to be Commagene, Judea, Coele-Syria, Phoenicia and Seleucid Syria, which by his time had devolved to Emesa. Of these, Coele-Syria and Phoenicia had no king; the dying Seleucid dynasty would have brought no advantage to Media; Emesa was only just now being organised as a minor principality and so would also have brought no advantage; and Judea was quite remote from Media. Only a marriage with Commagene is likely to have brought substantive advantage to Media. In fact it has been argued, on quite independent grounds, that Iotape, daughter of Artavasdes of Media, eventually married Mithridates III of Commagene in the late 20s. But this marriage does not fit the pattern of the other two: the marriage was not to Median king, and it is rather later than we would expect. The period of interest essentially corresponds to the reign of the Commagenian king Antiochus I. Therefore, Settipani proposes that there was a marriage of a Median king to one of his daughters. The known or postulated Median kings of the period are Darius, who was defeated by Pompey in 64 and marched in triumph in Rome, Ariobarzanes I, and his son Artavasdes I; in all probability, it was one of the last two. Settipani favours Artavasdes I, given that his daughter, Iotape, probably later married Mithridates III the son of Antiochus. In any case, he proposes that, if Strabo meant the three marriages to be understood as having equal dynastic value, we can reasonably infer that the father of Artabanus III and Vonones II (about whom nothing is known, but who is most likely, chronologically, a son of Artavasdes), was descended from this marriage.

The later Arsacid kings of Parthia, and in all probability the Arsacids of Armenia, are in all probability descended from Vonones II and Vologeses I. There is a very reasonable case, given in detail in Settipani's book, that descents from the Armenian Arsacids are traceable in outline, if not in complete detail in the early generations, to the present day. Thus, if Settipani's conjectures arising from his strict construction of Strabo's passage are correct, they provide a genealogical bridge from the Ptolemies to modern times.

This very tempting reconstruction is open to a number of challenges. The genealogy of the Armenian Arsacids, especially in the period before the Sassanid revolution, is highly doubtful, and it is not certain that they are in fact descended from Vonones II and Vologeses I. There is doubt whether Artabanus III and Vonones II are actually descended from the Atropatenian kings: Tacitus, Annals 2.3, refers to Artabanus as having spent his youth amongst the Dahae, i.e. in Hyrcania (modern Turkestan); but this may refer to his exile in a period when Rome dominated the kingdoms of the Causcasian area. Other interpretations of Strabo construe him much more loosely than Settipani does, allowing for earlier Armenian marriages and explaining the Syrian marriage as the imputed marriage of Iotape of Media to Mithridates III of Commagene (see e.g. R. D. Sullivan, Near Eastern Royalty and Rome 100-30 BC, 295ff). In a debate on this proposal on soc.genealogy.medieval in 1996, Stewart Baldwin has emphasised the number of conjectures involved in Settipani's reconstruction, all of which must be correct in order for the descent to succeed. He also proposed, both in 1996 and in another debate on this topic in 1998, as gedanken experiments, alternate reconstructions that do not result in Commagenian (and therefore not in Ptolemaic) descents. Those interested can extract the debate in full from the soc.genealogy.medieval archives. Ý

[14] Justin 39.3; he executed her for the murder of Cleopatra IV. Ý

[15] Estimated by fitting the coinage evidence in Antioch to the narrative of events in Justin 39.3 (A. R. Bellinger, The End of the Seleucids 87ff). From the coins, the start of the civil war between Antiochus VIII and Antiochus IX can be dated to the latter part of the year 199 SE = 114/3, which is the date for the earliest coins of Antiochus IX from Antioch, i.e. to 113. Cleopatra IV brought Antiochus IX a Cypriote fleet (Justin 39.3) shortly before this time. She appears to have been killed by Tryphaena the following year, c. 112, when coinage evidence (Babelon 1401 etc), naming king Antiochus (VIII) Epiphanes, dated year S = 200 SE = 113/2, and a distinctive Antiochene mintmark A, indicates that Antiochus VIII reoccupied Antioch.

Tryphaena's own death followed followed during the next brief reoccupation of Antioch by Antiochus IX. E. T. Newell, The Seleucid Mint of Antioch, 98f., assigned this to year 201 SE = 112/1, on the basis of an undated tetradrachm (SMA 386) that (a) bears the mark of a supervising magistrate otherwise unknown, and therefore was in office for only a short time (b) bears the Antiochene mintmark A, (c) is stylistically like the succeeding issues of Antiochus VIII and intermediate between the first and later issues of Antiochus IX, and (b) bears the subordinate mintmark G not previously met but also found on the succeeding issues of Antiochus VIII. However, the next dated Antiochene coinage of Antiochus IX (SNGCop. 409; BMC 24 and 25 -- see E. T. Newell, The Seleucid Mint of Antioch, 103) is dated GS = 203 SE = 110/09.

The question was reexamined by A. Houghton, SNR 72 (1993) 87 in light of subsequent coinage discoveries. It is undoubted the Antiochus VIII occupied Antioch in year BS = 202 SE = 111/0 (Babelon 1404 etc) and that Antiochus IX occupied Antioch in year GS = 203 SE = 110/09. Houghton lists a coin dated (S)G=(20)3 SE= 110/09 as proof that Antiochus VIII still controlled Antioch for part of that year. There is still no dated coinage for year AS = 201 SE = 112/1. In Houghton's view, there is no reason to doubt that Antiochus VIII occupied the city continuously throughout the period. If this is so, then Antiochus IXdid not reoccupy Antioch till c. 109, and cannot have executed Tryphaena till this time. However, Houghton SNR 72 (1993) 87, 104, admits that SMA 386 (his Series I of Antiochus IX) is "very close" to coins of Antioch, and that there is "no other satisfactory period at Antioch where these issues might fit." He suggests that they were minted at a mint in the vicinity, and suggests that A was a mint official who oversaw both locations.

It seems to me that Newell has the stronger case, and that Houghton's suggested alternate explanation -- a mint close to Antioch but not at Antioch, supervised by an official who was apparently working for the two warring kings simultaneously -- is special pleading. That being the case, I have been inclined to accept that Antiochus IX did reoccupy Antioch briefly in 112/1 and therefore did execute Tryphaena at this time.

However, in a recent review of the numismatic evidence for late Seleucid chronology, O. D. Hoover, Historia 56 (2007), 280 at 286 announced that a forthcoming study by A. Houghton, C. Lorber and O. Hoover, Seleucid Coins II, currently in press, had concluded that the tetradrachms studied by Newell and Houghton were not Antiochene at all, but had been minted in Cilicia, probably at Mopsus. If this is correct, then there is no evidence for Antioch being occupied by Antiochus IX in 112/1, and the next evidence for him is 110/9, as Houghton had argued in 1993, and Tryphaena's death must be dated to this year. Ý

Update Notes:

10 Feb 2002: Added individual trees

23 Feb 2002: Split into separate entry

2 March 2002: Added discussion of Houghtons reanalysis

of the date of the second occupation of Antioch by Antiochus IX.

23 Aug 2003: Added Xrefs to online Justin

23 Oct 2003: Added Xrefs to partial online Porphyry

24 Feb 2004: Added Xref to online Bellinger

13 Sep 2004: Add Xref to online Eusebius

11 Mar 2005: Added Greek transcription

16 Sep 2006: Added link to Packard Humaties DB

23 Oct 2007: Corrected reference to Philip II as king

of Damascus -- thanks to Petr Vesely

7 June 2008: Noted forthcoming study in SC2 relocating

Antiochus' mint in 112/1 and its implications for Tryphaena's

death -- thanks to Oliver Hoover

7 June 2008: Note Hoover's estimated dates for her

sons: Seleucus VI, Antiochus

XI, Philip I, Demetrius

III, Antiochus XII

28 Nov 2010: Fix broken Perseus links

Website © Chris Bennett, 2001-2011 -- All rights reserved