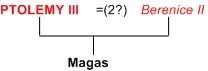

Magas1, son of Ptolemy III and Berenice II2, probably born c. November/December 2413, scalded to death in his bath by Theogos or Theodotus, an agent of Ptolemy IV, in late 222 or early 2214.

[1] PP VI 14534. Gr: MagaV. Ý

[2] Paternity: Exedra of Thermos: IG IX, I, I2, 56h. Paternity and maternity: Polybius 15.25.2. Ý

[3] According to Plutarch, Cleomenes 33, Magas was killed because he was popular with the army, which suggests some military experience. According to pHaun 6, he was sent on a mission to Asia Minor after the death of a king Seleucus, almost certainly Seleucus III, who died in 223 (Seleucid year 90: Babylonian chronicle published in A. J. Sachs & D. J. Wiseman, Iraq 16 (1954) 202), probably in the summer, as inferred by K. J. Beloch, Griechisches Geschichte IV.2 196 based on the circumstances of his murder while campaigning in the Taurus as described by Polybius 4.48.8. Magas should be at least about 17 at this time, i.e. he was born in or before late summer 240.

We may refine this estimate through a chronological study of the exedra of Thermos (IG IX, I, I2, 56), which to the best of my knowledge has not been undertaken in the literature (W. Huss, CdE 50 (1975) 312 and the sources therein). This monument was arranged as a P-shape. It lists the royal family in the following order: (a) king Ptolemy (b) Ptolemy (c) queen Berenice (d) Arsinoe (e) Berenice (f) [Unknown son] (g) Alexander (h) Magas. A statue originally stood in front of each name, and that of king Ptolemy was on the left arm of the U, prominently facing the viewer. The right arm is completely lost, but presumably another statue stood there. G. Blum (BCH 39 (1915) 17, 20 n. 2), supposing the exedra to have been erected in 230 or later because of the political climate of those years, suggested that the princess Berenice named at (e) was a second child of that name, since the first princess Berenice had died in 238. He also notes that the existence of other children is not mentioned on the Canopus Decree (OGIS 56), and therefore argues that they were all born after this date. However, pHaun 6 appears to show that Magas at least was born earlier.

J. Bingen, in Akten des 21. Internationalen Papyrologenkongresses Berlin, 13.-19.8.1995 I 88 noted that iPhilae 4 = OGIS 61 refers to the "small children" (teknia, not tekna as had previously been read) of Ptolemy III and Berenice II, and so at least two children must have been born before the date of this inscription. Bingen argued that, given the absence of the divine epiklesis Euergetes for Ptolemy III, it must have been erected before September 243; he proposed to date it to summer of 244.

This argument was refuted by an observation of C. G. Johnson, Historia 51 (2002) 112, who noted that iPhilae 8 = OGIS 98, dating from late in the reign of Ptolemy V, was the earliest dedicatory inscription in which the royal couple (as opposed to their ancestors) appeared as deities. J. Bingen, REG 115 (2002) 750 no 526, consequently withdrew the argument.

However, W. Clarysse in L. Mooren (ed.), Politics, Administration and Society in the Hellenistic and Roman World, 29 at 37, argues that there are several indirect allusions to a royal journey of Ptolemy III in Zenon and Tebtunis papyri datable to c. February 243 (an elaborate party for the king's birthday: pLond 7.2056 (undated), pCairZen 3.59358 (year 4 Choiak 12 = 1 Feb. 243), pRyl 4.568; an (undated) list of guests arguably for an royal reception: PSI 5.548; ordering of luxury supplies: pTebt 3.1.748 and pTebt 3.1.749). He reasonably proposes that iPhilae 4 is part of the same journey, though it cannot yet be proved.

Since the exedra commemorates an alliance between Ptolemy III and the Aetolian League, it seems to me that the missing end must have represented the League, either through a patron deity, such as Apollo, as suggested by Weinrach (IG IX, I, I2, p40), or through some other symbol. As to the date of the exedra, most discussion (e.g. Huss op. cit.) places it near the end of Ptolemy III's reign, when a known alliance between him and the League had defeated Demetrius II of Macedon, but it seems to me that the internal evidence of the exedra, showing the princess Berenice as apparently living, forces a date before or very shortly after her death in early 238. This period of Egyptian/Aetolian relations is much less known, but it corresponds to the period of peace following the treaty between the Achaean and Aetolian Leagues of c. 240 and preceding the outbreak of the Demetrian war in the early 230s (J. D. Grainger, The League of the Aitolians 155, 217f.). An exedra with a general dedication to the Hellenic peoples seems appropriate for this period.

Without a clear reason to date the exedra later, we may suppose that the Berenice named on it was believed to be alive at the time it was erected. It follows that the exedra shows all of Ptolemy III's children born before February 238, the date of the death of Berenice, as given by the Canopus Decree (OGIS 56).

G. Blum (BCH 39 (1915) 17) suggested that the lost statue on the right wing of the exedra may have been the Berenice of the Canopic Decree, apotheosized as a deity, and the Berenice of the base was a second daughter of that name. E. Kosmetatou (Tyche 17 (2002), 103 at 110) suggests that the Berenice named on the Delphic analog of this monument, considered below, was also posthumous and deified. In both cases, this suggestion is made to support a possible later date of the monument.

W. Huss, CdE 50 (1975) 312 objected that there is no reason to suppose that the Ptolemaic deification of the infant Berenice would have been recognised by the Aitolian League, and the same remark applies to the Delphic Amphictyony. I agree. Neither Blum nor Kosmetatou advance any evidence to support the plausibliity of the suggestion.

Since Arsinoe bears the name of her paternal grandmother, she was almost certainly the older of the two sisters, and so we may reasonably assume that the sons and daughters are each listed in relative order of birth. Magas was thus the youngest son, born (as we have seen from pHaun 6) in or before late summer 240. Additionally, since Berenice was a viable child, she was probably at least a year old at the time of her death.

Since the daughters and the sons are each grouped together on the exedra, it is possible that it does not reflect the order of birth of the daughters relative to the sons. We may be able to determine more about the actual order of birth from another monument, R. Flacelière, Fouilles de Delphes III:4:2 no 233, pp 275ff. This monument is much more fragmentary than the exedra, but portions of the dedicatory inscription are preserved. At certain points above this inscription there are fragments of other inscriptions that originally identified certain statues on the monument. These clearly named a "basilissa" Arsinoe, daughter of king Ptolemy and queen Berenice, at the leftmost end of the dedicatory inscription, another child of king Ptolemy and queen [Bere]ni[ce] partway along it, and a "basillissa" or "basileos", child of a king Ptolemy and a queen [Berenice?], at the rightmost end of that inscription. In view of the position and the maternity of the intermediate child, these children must belong to Ptolemy III and Berenice II.

If one uses Flacelière's reconstruction of the dedicatory inscription, which was closely modelled on that of Thermos, as a guide, the entire dedication was around 8 metres long, and the second surviving fragment was about 1.5 meters from the first. Assuming equal spacing, there would then have been three more statues between second and third surviving fragments, for a total of six. On this basis, they were almost certainly those of Ptolemy III's children. The last child was the "basilissa" Berenice, and the royal sons were named between the two daughters. The monument would certainly also have contained statues of the king and queen, and perhaps additional statues, e.g. of ancestors or divinities, as at Thermos. These would have been placed outside the dedicatory inscription, with at least that of the king being to the left of the oldest child.

On this reconstruction, the heir, Ptolemy (IV), would then have been named after his sister. It seems reasonable to conclude that such an ordering reflects the birth ordering. Combining the two monuments, the children would then have been born in the order Arsinoe, Ptolemy, [?Lysimachus], Magas and Berenice.

It is most likely that Berenice II was married shortly after the accession of Ptolemy III c. February 246, and we know that he was absent campaigning from September 246 for about a year. Assuming that the eldest child (Arsinoe) was conceived in the initial 7 months of marriage, the remaining five were therefore born between about May/June 244 and Jan/Feb 239, a period of about 57 months. If there were no twins, this gives an average spacing of about 14 months between children.

Therefore, the birth dates of the children of Ptolemy III and Berenice II named in the exedra may reasonably be estimated as follows:

Arsinoe November 246 - June 245

Ptolemy May/June 244

[Unknown] July/August 243

Alexander September/October 242

Magas November/December 241

Berenice January/February 239It should be stressed, firstly, that the birth dates apply to any birth order, provided there were no twins; they only depend on the number of children and the total available time. And secondly, these dates are only mean estimates -- for children 2-6 a couple of months variance either way on any indivdual birth is possible.

An extended version of the above analysis was formally published in C. J. Bennett, ZPE 138 (2002) 141. I have seen two responses.

In that publication, I incautiously accepted Flacelière's reconstruction of the dedicatory inscription as a given, rather than just as example of a type, and I was also so foolish as to suggest that the Delphic monument could have been an exedra, similar to that at Thermos; perhaps with the statues of Ptolemy III and Berenice II on either wing. E. Kosmetatou, Tyche 17 (2002), 103, quite properly notes that other reconstructions of the inscription are possible and that there is no actual evidence that the monument was an exedra. She argues that the inscription could well have been longer, though she thinks it is unlikely to have been shorter; she herself suggests 9-10 meters rather than 8.

She suggests that dynastic considerations required that the royal couple and the heir be grouped together, and therefore places all three to the left of Arsinoe, and the dedication. The fragment of the prince who I suggest as Ptolemy (IV) she proposes to be Lysimachus(?), the next brother. Curiously, she still accepts the last fragment as being the princess Berenice, although she regards the number of statues along the dedication to be uncertain. She supposes that there were statues of ancestors or gods to the right of this.

Her reasons for her identification of the last fragment are not stated: either Ptolemy II or Arsinoe II would also seem to be possible on her logic. Further, this considerably increases the mean distance between the statues of the three children after Lysimachus(?), unless there were additional statues (presumably for additional children, now lost). Indeed, on this basis the mean distance between the 5 children covered by the inscription must be well over 2 meters, and, assuming an oblong platform as Kosmetatou does, it must have extended at least 6 or 7 meters to the left of the start of the dedicatory inscription. Unless the placement of the dedication was very significantly off-center, there must have been at least two additional statues to the right of Berenice, for a total length of well over 20 meters.

The architectural details of the monument are unimportant here, except insofar as they affect the identities and placement of the statues; thus, it really doesn't matter whether it was an exedra, nor is it terribly important where Berenice II was placed. Indeed, the net chronological impact of Kosmetatou's argument is not as significant as she suggests, unless we discard the identification of the last fragment with the princess Berenice, an identification she accepts. Arsinoe is still named before all the younger brothers: at worst, it is unclear whether she or Ptolemy was the first named child. Birth order is still the most likely explanation for this position. The only alternative that I can see is to suppose that Arsinoe had already been selected as wife of the heir: possible, but rather unlikely if the monument dates to 238.

On the other hand, if we identify the last fragment as Ptolemy II or Arsinoe II rather than the princess Berenice, then we have no genealogical basis for dating the monument more closely than some time in the reign of Ptolemy III, since we would not then know whether Berenice appeared anywhere on it, nor how many children there were at all. In this case we would be left with only the evidence of the Thermos monument, and no restrictions on Arsinoe's position in the first five children. In this case, Magas could have been born as early as summer of 242.

Secondly, L. Criscuolo, Chiron 33 (2003) 311 at 325 n. 65 has raised two objections to the analysis. First, she argues that political circumstances favour a date later than 238, around the accord between Ptolemy III and Antigonus Doson that took place in c. year 20 = 228/7. She also finds the biochronology derived above "preoccupante" (troubling), noting that the only solid fact is given by iPhilae 4, that there was more than one child born before 243 (and, as we have seen above, that date is less certain than either she or I supposed).

I certainly agree that political circumstances, considered in isolation, are consistent with other dates, and can only repeat what I have already said: political circumstances, so far as they are known, are also consistent with a date in 238, a point which she does not refute. The key point, which Criscuolo ignores (though I imagine counter-conjectures can be made), is that any other date requires an explanation of why a very dead baby was included in the family group; as argued above, the only suggestion on the table -- deification -- is without evidentiary support.

As to the rate of production of children, I fully agree that a date of 238 implies that Berenice II was reduced to being a baby factory for a while, but it is certainly possible, as is well-known, that children could be born at this rate. And, after all, iPhilae 4 is not the only known datum. We also have pHaun 6 on Magas, and the Canopus Decree on Berenice, both more certainly dated than iPhilae 4 -- and human reproductive biology has not changed significantly between the 3rd century BC and the 21st century AD, and may reasonably be taken into account.

That being said, Criscuolo also presents a rather more plausible (though still unconvincing) argument that Berenice II was married in 249, not 246. Granting this date for the sake of argument, the possible date ranges for the birth of each child become stretched out, by up to two years. The above analysis would remain useful, but for setting a terminus ante quem for the birth of each child. Ý

[4] Polybius 15.25.2; Pseudo-Plutarch Proverb. Alexandr. 13 ed O. Crusius, which provides the lurid detail, gives the name of his assassin as Theogos. C. C. Edgar, BSAA 19 (1920) 117, suggested the name should be corrected to Theogenes and further proposed to identify this Theogenes with Theogenes the dioiketes to Ptolemy IV, and possibly stepfather to Agathoclea. P. Maas, JEA 31 74 n. 1, cautions that the name Theogenes was quite common at this period. In any case, pHaun 6 appears to name the killer of Magas as Theodotus the Aetolian. This individual later defected to Antiochus III (Polybius 5.40) and attempted to assassinate Ptolemy IV just before the battle of Raphia (Polybius 5.81, III Maccabees 1.2). Ý

Update Notes:

10 Feb 2002: Added individual trees

20 Feb 2002: Split into separate entry

18 May 2003: Added Xrefs to the Lacus Curtius edition

of Polybius

24 Feb 2004: Added Xref to Canopus Decree

2 Dec 2004: Added comments on Criscuolo's

objections to the analysis of birth dates.

11 Mar 2005: Added Greek transcription

26 Aug 2006: Add links to BCH 35 and FD III.

13 Sep 2006: Link to Packard Humanities DB

11 Nov 2007: Note Johnson and

Clarysse's arguments re the date of Ptolemy III's visit to the

chora, affecting the date of iPhilae 4

26 July 2008: Added response to Kosmetatou's

critique of my use of FD III 4 2 233 to argue a birth order for

Ptolemy III's children.

26 Nov 2010: Fix broken DDbDP links

Website © Chris Bennett, 2001-2011 -- All rights reserved